1. INTRODUCTION

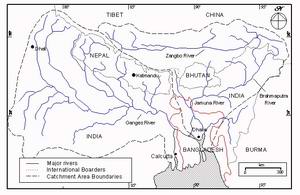

Three major rivers of the region, namely the Ganges, the Brahmaputra and the Meghna/Barak (GBM) have a common terminus into the Bay of Bengal and thus form a river system. About 10 per cent of global population is living in the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta. Sediments carrying by the rivers transforming the landscpe to one of the most fertile lands of the world.The Ganges-Brahmaputra- Meghna river system carries over 2.9 billion tonnes sediments (one third of global sediment transport to the world ocean, Milman et al., 1983) into the Bay of Bengal. Thousands of years of civilisation flourished along the Ganges-Brahmaputra rivers. About 18 kilometrs of sediment thus deposited in the sinking basin (which still do today) making the world's deepest sedimentary basin of the world. The Bengal basin is tectonically active.

Three major rivers of the region, namely the Ganges, the Brahmaputra and the Meghna/Barak (GBM) have a common terminus into the Bay of Bengal and thus form a river system. About 10 per cent of global population is living in the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta. Sediments carrying by the rivers transforming the landscpe to one of the most fertile lands of the world.The Ganges-Brahmaputra- Meghna river system carries over 2.9 billion tonnes sediments (one third of global sediment transport to the world ocean, Milman et al., 1983) into the Bay of Bengal. Thousands of years of civilisation flourished along the Ganges-Brahmaputra rivers. About 18 kilometrs of sediment thus deposited in the sinking basin (which still do today) making the world's deepest sedimentary basin of the world. The Bengal basin is tectonically active.

|

|

Brahmaputra River is Tibet's longest and the world's highest inaltitude. This 2,057km long river drains an area of 240,000 sq.km and provides irrigation for some of Tibet's major agricultural regions. Tibetans call it "Mother River".

Brahmaputra River is Tibet's longest and the world's highest inaltitude. This 2,057km long river drains an area of 240,000 sq.km and provides irrigation for some of Tibet's major agricultural regions. Tibetans call it "Mother River".

The remaining two countries, India and Bangladesh, depend heavily on the waters from the GBM system.

Thus, the dwindling supply of water in the dry season has become one of the key issues between India and Bangladesh. The situation is particularly critical for Bangladesh, as about 80% of its annual fresh wtersupply comes as transboundary inflows through 54 common rivers with India.

The Brahmaputra River shifted its course dramatically at the turn of 19th century, when it abondoned the old Brahmaputra, and took a new, more westerly path. Perhaps ready for a further major shift, which must not be provoked by ill-judged works on the river.

This river system falls in a number of countries in the South Asia region, including China, India, Nepal and Bangladesh. Of these, China contributes solely to the flow of the Brahmaputra, and Nepal to the flow of the Ganges. Both China and Nepal are upper riparian countries and the tributaries originating in these countries contributing to the GBM system are not yet fully utilised. As a result, these countries do not face any contentious water issue with their lower riparian neighbours.

The Ganges delta covers 1,093,450 km2 in total of which Bangladesh shares 46,000 km2, Indian 861,400 km2, Nepal 146,000 km2 and Tibet shares 40,4000 km2. Bangladesh though accommodates only 4.0 percent of length but the Ganges delta covers 36.0 percent area of Bangladesh and meets 20.0 percent of fresh water requirement.

The three major rivers such as Ganges, the Brahmaputra and their tributaries. Bangladesh, as a tropical country, faces cyclones and floods every year causing havoc to the lives of millions of people.

Thus the paradox of water goes on; water is the source of life but it can also be the end of life. For us especially, water is vital for our thirsty crops, yet floods can often wash them away along with our very lives while droughts in our neighbouring countries cause untold miseries. Meanwhile, unplanned urbanisation and encroachment of our water bodies, has ensured that there is an acute shortage of water for drinking and other essential purposes. Unchecked polluting of our lakes and rivers has contaminated our water supplies, threatening our health and again, our lives. There is no doubt that human negligence and abuse has resulted in this pathetic state of being where water is either too much or too little but somehow never just enough. The workshop may not solve our water paradox but it does raise the point that there is so much we can do to ease the crisis. We must clean up our water bodies and stop polluting them or filling them up with our greed; We must save the water we have and refrain from wasting it whether in terms of not letting the water run while we brush our teeth to collecting the water from the heavens when it pours. For many it may mean adopting less wasteful lifestyles, using less energy, being a little more restrained. There is a lesson to be learned for every nation, whether rich or poor, to make sure that the pure relationship of man and water is once again, restored

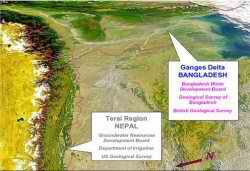

In this dramatic view of the northern Indian subcontinent, the Brahmaputra River courses from the top of the image (east) through Bangladesh to the Bay of Bengal while the Ganges proceeds from the west also to the Bay. The Himalayas lie along the left side of this SeaWiFS image.

In this dramatic view of the northern Indian subcontinent, the Brahmaputra River courses from the top of the image (east) through Bangladesh to the Bay of Bengal while the Ganges proceeds from the west also to the Bay. The Himalayas lie along the left side of this SeaWiFS image.

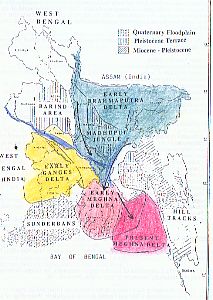

The earliest deltaic arcs in Recent times are two simultaneous development called the Ganges Delta and Brahmaputra delta. The present Ganges-Brahmaputra delta, where much of the sediments accumulates, is represented onshore by a low lying flood plain covering more than 90,000 sq. km of present day Bangladesh and India, which is characterized by its dynamic growth.

The earliest deltaic arcs in Recent times are two simultaneous development called the Ganges Delta and Brahmaputra delta. The present Ganges-Brahmaputra delta, where much of the sediments accumulates, is represented onshore by a low lying flood plain covering more than 90,000 sq. km of present day Bangladesh and India, which is characterized by its dynamic growth.

The Early Bramaputra Delta , in the south of Shillong Massif (Assam, India) and Early Ganges Delta, in the districts of Kustia, Jessore and Khulna evolved from the north and northeastern part of the country. These two rivers are then diverted and have built a third delataic arc. The Early Meghna Delta: .

The Present Day Delta is actively and rapidly pushing into the eastern side of the Bay of Bengal (Landsat Imagery, Morton and Khan, 1979). Between 1972 and 1977 3,600 hectares were added to the Bay of Bengal. If no human intervention occurs, it is possible to reclaim land of about 5 to 10 thousand square miles mostly in the central coastal region.

Sediments of the confluent Ganges and river today are deposited predominantly in the huge subaerial delta of these rivers(central part of the fan between northern part of the Ninetyeast Ridge and sri Lanka - Fig. ). The present tectonics of the bay of bengal region have important implications for the future orogenic fate of the continental rise and fan sediments underlying the bay.

Sediments of the confluent Ganges and river today are deposited predominantly in the huge subaerial delta of these rivers(central part of the fan between northern part of the Ninetyeast Ridge and sri Lanka - Fig. ). The present tectonics of the bay of bengal region have important implications for the future orogenic fate of the continental rise and fan sediments underlying the bay.

Present relative plate motion between the Indian plate and the Asian plate apparently in a northeast-southeast at a rate of convergence between 5 and 6 cm per year. Tectonics of this region are more complicated when examined in the light of major plate motions. India is still moving northeasterly into Asia.. Seismic activity continues along the Sunda

Arc up to eastern Himalayan sytaxis, across the Himalayan Mountains, under

the Tibetian Plateau and southern China. Since thermal subsidence of the

passive margin is still active, sedimentation delta complex continues to be considerable.

Himalayan dams pose threat to Bangladesh

India, Pakistan, Nepal and Bhutan have planned a total of 552 hydropower projects in Himalayan region, of which some have already been built and some are under construction, that may have far-reaching impacts on downstream Bangladesh, informed sources said.

Himalayan region is the centre point from where scores of small and large Asian rivers originated and run through. The Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Irabati are some of those. Bangladesh shares water of 54 rivers with India and 3 with Myanmar.

"If those upstream countries divert normal water flow through these dams, it will dry up many Bangladeshi rivers ruin irrigation system, kill lives in the water bodies. On the other hand, if they do not manage water properly it will inundate a big part of the country during rainy season," Joint River Commission (JRC) Member Mir Sajjad Hossen told The New Nation.

A study of the 'International Rivers', an US based non-governmental organisation that protects rivers and defends the rights of communities, revealed that India has already built 74 dams, Nepal 15, Pakistan 6 and Bhutan 5 in Himalayan region in the recent years. It also found that 37 Indian, 7 Pakistani and 2 Nepalese dam are under construction in that area. The study also identified that India has planned to build 318 dams, Nepal 37, Pakistan 35 and Bhutan 16 more dams in this region to add over 1,50,000 Megawatts (MW) of additional electricity capacity in the next 20 years.

Sajjad Hossen said that the proposed and under construction dams, Tipaimukh dam is one of those, will change downstream flows, affecting agriculture and fisheries and threatening livelihoods of many people in Bangladesh.

"These countries are supposed to share information with Bangladesh before taking any such step of building new dams, but they are not doing so. We have asked them for information. What we can do if they do not obey the river interlinking rules," said Hossen expressing helplessness against upstream powerful countries.

The author of the 'Mountains of Concrete: Dam Building in the Himalayas' Shripad Dharmadhikary wrote: "If all the planned capacity expansion materialises, the Himalayan region could possibly have the highest concentration of dams in the world. This dam building activity will fundamentally transform the landscape, ecology and economy of the region and will have far-reaching impacts all the way down to the river deltas."

Bhutan is planning a capacity expansion of about 10,000 MW in the next 10 years. Among the projects being planned for the near future are the 1,095 MW Puntansangchu-I and the 600 MW Mangdechhu projects.

Nepal is planning to install hydropower capacity of 22,000 MW in the coming years. For its own needs, Nepal plans to add 1,750 MW by the year 2020-2021, mostly through small and medium projects. Rest, mainly from the bigger projects, is planned for selling power to India. Pakistan has plans to add 10,000 MW through five projects by the year 2016. Another 14 projects totalling about 21,000 MW are under study for construction by 2025. The government is pushing for the immediate implementation of the massive 4,500 MW Diamer-Bhasha project.

India declared its intentions with the launching of the "50,000 MW Initiative" on May 24, 2003. This initiative fast tracked hydropower development by taking up time-bound preparation of the Preliminary Feasibility Reports (PFRs) of 162 new hydroelectric schemes totalling around 50,000 MW. India has plans to build this capacity by 2017 and then, in the 10 years following, to add another 67,000 MW of hydropower. Construction is ongoing for many of the projects including the 2,000 MW Lower Subansiri project, the 400 MW Koteshwar project and the 1,000 MW Karcham Wangtoo, to name a few. Many of these projects are already under construction.

Due to various obstacles of dams, barrages and hydropower projects in Himalayan region, the source of water of rivers, Bangladesh get lesser water in rivers flowing throughout the country. The lean water flow in the rivers has already cast negative impact on ecology, aquatic life, and irrigation.

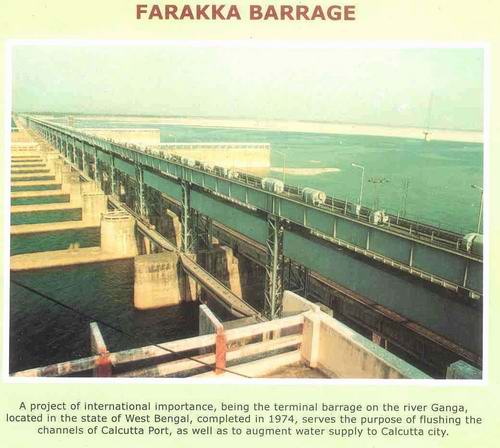

According to the Ganges treaty, signed in 1996, Bangladesh and India will equally share water if water flow is up to 70,000 cusec or less in the Farakka barrage point. Bangladesh will get 35,000 cusec of water and India will get the rest if water at Farakka point is between 70,000 and 75,000 cusec.

If water at Frakka point reaches more than 75,000 cusec, India will get 40,000 cusec and Bangladesh will get the rest. But India never followed these terms and conditions of the accord and released meagre quantity of water for Bangladesh, it was alleged.

The JRC statistics shows that Bangladesh did not get its proper share of water since signing of the treaty. In 1999 Bangladesh got 1,033 cusec of water at Teesta barrage point against its normal requirements of 10,000 cusec of water. After JRC meeting in 2000 the water flow rose to 4,530 cusec, in January 2001 it reduced to 1406 cusec, in January 2002 to 1,000 cusec, in January 2003 to 1,100 cusec, in November 2006 to 950 cusec, in January 2007 to 525 cusec and in January 2008 to 1,500 cusec.

Due to less quantum of water supply through Teesta barrage thousands of acres of land in the country's northern districts lack irrigation posing threat to Boro rice cultivation. Around 15 small rivers are also drying up and about to die due to the same reason. The Teesta River itself becomes a thin canal for less volume of water supply from the upper riparian Indian part. The rivers include: Kortoa, Dudhkomol, Jingira, Dhorla, Bangali, Ghaghot, Atrai, Akhira, Manas, Katakhali, Ichamoti, Punorvoba, Burighora and Dhauk also drying due to less water supply. WDB officials said sustainability of these rivers is impossible unless India supplies adequate water through the barrage (The New Nation, March 09, 2009).

Habitat and Ecosystems

Over 73% of the Brahmaputra River watershed's originial forest is gone. The remaining forests are disappearing at 10% per year. Currently only 4% of the land is in protected areas. The area supports 4 endemic bird habitats and one RAMSAR-listed wetland.126 fish species also call the Brahmaputra basin home (WRI).

The ecoregion covering the Brahmaputra River in northeast India harbors India's largest elephant population (Rodgers and Panwar 1988), the world's largest population of the greater one-horned rhinoceros, tigers (Panthera tigris), and wild water buffalo (Bubalus arnee) (WII 1997). The ecoregion overlaps with a high-priority (Level I) ecosystem that extends north to include the subtropical and temperate forests of the Himalayan midhills (Wikramanayake et al. 1999).

The known mammal fauna consists of 122 species, including 2 near-endemic species. Of these, the pygmy hog and the hispid hare are confined to the grassland habitats. At present, twelve protected areas cover about 2,500 km2 of intact habitat, or 5 percent of the ecoregion. Of these, Manas, Dibru-Saikowa, Kaziranga, and Mehao are the larger and more important reserves. Mehao extends over two other ecoregions and is only partially within this ecoregion. Kaziranga has the world's largest population of the greater one-horned rhinoceros, estimated at 1,100 individuals (Foose and van Strien 1997). Because of the large number of wide-ranging large vertebrates in this ecoregion, additional protection is urgently needed. Specifically, habitat connectivity should be provided within the Buxa-Manas complex and the Barail-Intanki-Kaziranga complex to allow elephants to disperse and migrate (Rodgers and Panwar 1988).

The ecoregion represents the swath of semi-evergreen forests along the upper Brahmaputra River plains.Assam Valley semi-evergreen forest, Assam alluvial plains semi-evergreen forest, eastern submontane semi-evergreen forest, sub-Himalayan light alluvial semi-evergreen forest, eastern alluvial secondary semi-evergreen forest, sub-Himalayan secondary wet mixed forest, and Cachar semi-evergreen forest. But most of the ecoregion's original semi-evergreen forests have been converted to grasslands by centuries of fire and other human influences. Only small patches of forests now remain.

|

Bangladesh covers an area of about 145,000 km2. The Delta of two of the world's largest rivers -the Ganges and the Brahmaputra, together with the Meghna River empty into the Bay of Bengal -occupies 80 per cent of the surface. The mean annual discharge of these rivers is 103,000 m3/ sec from a catchment of about 1.7 million km2. This compares with the Mekong River which has an average discharge of 14,000 m3/sec and a catchment of 0.8 million km2. CONTROLLING floods in the plains is laudable, but it is not a harmless activity as far as near-shore fish are concerned. Almost all fish-harvesting in Bangladesh is near the shore. All the dams, culverts, embankments and river closures installed in Bangladesh to protect 3 million, flood-prone hectares, have led to a considerable decline in fish harvest, according to a study done by the University of Chittagong.

"This happens because of the obstruction to the natural migration of fish from fresh water to brackish water habitats and vice versa, for breeding and feeding," explained M J U Chowdhury, head of the university's marine science institute.

There was a phrase in Bangla “Mchhe bhate Bangali” (Bangali feed on fish and rice). But this phrase is not in use any more. With changes in the global climate, uncontrolled fishing, water pollution etc. - fishes are now becoming scarce and more expensive. Nowadays, the availability of farm fishes is going up, but the number of fish markets is going down. |

The Brahmaputra's Changing River Ecology

Mighty Brahmaputra, its tributaries getting extinct

World's largest river system

The chemistry of the Ganga and the Yamuna in the lower reaches is by and large dictated by the chemistry of their tributaries and their mixing proportions. Illite is the dominant clay mineral (about 80%) in the bedload sediments of the highland rivers. Kaolinite and chlorite together constitute the remaining 20% of the clays. In the Chambal, Betwa and Ken, smectite accounts for about 80% of the clays. This difference in the clay mineral composition of the bed sediments is a reflection of the differences in the geology of their drainage basins. The Ganga-Brahmaputra river system transports about 130 million tons of dissolved salts to the Bay of Bengal, which is nearly 3% of the global river flux to the oceans. The chemical denudation rates for the Ganga and the Brahmaputra basins are about 72 and 105 tons· km - · yr -1 , respectively, which are factors of 2 to 3 higher than the global average.

|

River-linking plan not abandoned

BSS, NEW DELHI, October 7, 2004: Indian Water Resources Minister Priyaranjan Dasmunshi has told President APJ Abdul Kalam that the Congress-led UPA coalition government is committed to implementing inter-linking of South Asian rivers. The highly controversial project, adopted by the immediate past BJP-led NDA government, plans to divert waters of international rivers, which if implemented would drastically affect the region's co-riparian countries, particularly the lower riparian Bangladesh.

The minister informed Kalam that the new Indian government would give priority to the south-bound peninsular rivers in the first phase of the project. He also informed the president, an advocate of the project, that the Water Resources Ministry of India directed the National Water Development Agency to complete the full feasibility reports of 18-river links out of 30 by December next year. Dasmunshi told him that the ministry also set up a technical group of engineers for working out a consensus plan on "priority links" by October 31. The mega project, estimated to cost 5,60,000 crore Indian rupees, raised protests from India's neighbours, particularly Bangladesh, besides several Indian provinces as well as environmental groups, who consider it could spell disaster for the entire region.

IUCN to set up a Ganges, Brahmaputra and Megna Rivers Commission to conserve natural river systemsThe IUCN World Conservation Congress adopted a resolution Wednesday to help set up a Ganges, Brahmaputra and Megna Rivers Commission to conserve natural river systems. Representatives of the government and nongovernmental organisations supported the resolution raised by Bangladesh although neighbouring India opposed it at the 3rd IUCN Congress in the Thai capital Bangkok. India's controversial river interlinking project made headlines time and again in both the domestic and international press for the last two years. The $120 billion project designed to interlink 37 rivers including the Ganges and Brahmaputra to divert water, has been termed by the Bangladeshi experts as a 'death trap', which will cause an ecological and economic disaster in the lower-riparian Bangladesh. India also plans to construct a controversial barrage on river Barak, upstream of Meghna, a major river system of Bangladesh. The IUCN resolution was raised by Hasna Jashimuddin Moudud. Opposing the resolution, the Indian delegates proposed to withdraw it saying, "The motion should be taken back as integrated water resource management as a bilateral issue." About 65 per cent government delegates and 88 per cent NGO delegates supported the resolution while 11 per cent government delegates opposed it. Adopting the resolution, the IUCN congress called upon the civil society and governments in the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna basins to promote dialogue and cooperation towards sustainable development of trans-boundary water resources. The congress urged the IUCN director general to promote basin-wise river management and regional cooperation in all international river basins and help of setting up a Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna Rivers Basin Commission to conserve natural river systems. The congress also urged all bilateral and multilateral development agencies and government agencies to support a Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna River Basin Commission, to promote regional cooperation and sustainable management of water resources (New Age, November 25, 2004). |

River-linking a state vs people conflict

'We also will continue to raise our voices in India as the project creates concern for people living in the river valleys there [India]', Medha said. She is visiting Bangladesh to attend a three-day international conference on 'Regional Cooperation on Transboundary Rivers: Impact of the Indian River-Linking Project' that began on December 17. Later, on Friday evening, she addressed a general session of the conference at the auditorium of the Institution of Engineers of Bangladesh. Medha Patkar spearheads the Narmada Bachao Andolan, the 20-year-old struggle against the dam project that threatens the right to life and livelihood of the people of India's Narmada valley, which has grown into one of the world's largest non-violent social movements. She has been at the centre of the struggle, gaining worldwide renown for sharp analysis and courageous activism that has included long fasts, police beatings and jail. The Narmada Sagar, one of the 30 major dams on the Narmada and one of the two biggest dams, is likely to submerge 254 villages. Medha said that interlinking of rivers to divert one-third of the water of the river Brahmaputra, 60 per cent of which is used for irrigation and maintaining the ecosystem of the Brahmaputra basin, should not happen unless Bangladesh is consulted. 'Bangladesh should raise its voice not for information [about the project] only; Bangladesh should also be involved in the consultation to determine the feasibility of the project,' said Medha, who also leads an influential network of over 150 mass-based movements across India called the National Alliance of People's Movements. Medha, a former faculty member of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, also emphasised the need to involve other neighbouring countries, that are sharing the same river systems, in the movement against the much-talked-about project which, in her words, 'is the worst project one could ever think of'. 'The project is going to cause devastation, which many people are not able to understand, to the people of the region, many more times than the Farakka Barrage caused in Bangladesh and the Narmada Dam in India,' she said, in her warning about the dangers of the $120 billion project. 'It will destroy the ecosystem, which really supports the human habitat, the fish and also the forest. In Bangladesh, for example, the very large number of people who live in the Ganga, Brahmaputra and Megna deltas, may lose their life support system, that has already been disrupted by the Farakka Barrage, by destruction of aquatic wealth and causing huge floods without really supporting the flood-plain,' she said. 'Intra-state conflict will come up within India and regional conflict will be emerging within South Asia too,' Medha warned. Medha, however, was less enthusiastic about the 'government-level dialogues' to resolve disputes regarding sharing the water of common rivers. 'I don't believe that a state can initiate a genuine dialogue as the nation-states in South Asia are more influenced and controlled by the global powers than the people in the countries.' 'The people to people dialogue can create the alternatives that could compel the states to include the issue in their political agenda and give rise to the right kind of intervention in ongoing politics which is exploiting the people,' she said. 'Unity of the civil society of South Asia has to be strengthened. River valley organisations of the region will have to come together to unitedly fight the battle,' Medha said. 'It should also be the concern of the human rights organisations and those who are fighting [against] the globalisation-liberalisation paradigm. 'I think, at the moment, we only can take a strong position against the impractical plan [river-linking], which is in a way the manifestation of a colonial tendency within the country [India] and within the region [South Asia] where people have always been and are being exploited,' she said. Medha told, 'We are facing the same kind of challenges, which have come up because of the states' wrong approach to natural resources management and at the cost of the common people - in favour of urban industrial societies within our own nation-states.' She warned that the 'conflict' should not be seen as an "India versus Bangladesh issue" at all. 'Rather it should be seen as "states versus people conflict" caused by the governments' wrong and anti-people position and 'state versus science, experience and conscience of the civil society at large'. When asked about another one of India's controversial project, the Tipaimukh Dam, a multipurpose barrage on the river Borak upstream of the Meghna, a major river system of Bangladesh, Medha said, 'We are against the Tipaimukh dam.' 'The north-east of India has become the target now…which is clear because during the World Water Forum, held in the Netherlands, all of those who represented the Indian government were talking more about the north-east and the north-eastern rivers than anything else,' said Medha, also a commissioner of the World Commission on Dams, the first independent global body formed to examine the water, power and alternative issues related to dams across the world. 'It is because many of the bilateral and multilateral agencies want to invest in the water sector in South Asia, although this kind of dam will ultimately destroy the natural ecosystem and the human population which is a part of that,' she said. She criticised the role of the multinational lending agencies, including the World Bank, which, in her words, 'are keen to tap every river'. 'Whether it is exploiting the Tipaimukh or the Ganga or the Brahmaputra, they [lending agencies] will be involved in it,' Medha predicted. 'Are we really for this kind of privatisation of rivers?' she asked. 'Are we selling out our rivers, which will adversely affect the people's sovereignty?' (New Age, December 19, 2004) |

Bangladdesh concerned by Indian River Linking project

A Bangladesh parliamentary panel has expressed concern over India’s funding its river-linking project. Bangladesh fears such diversions will affect the flow of the rivers in Bangladesh. India and Bangladesh share 54 common rivers. They have been engaged in disputes over sharing of Ganges water and the Teesta water sharing . The Indian river linking project will add further fuel into the water dispute between the two neighbours.

The Indian mega project of river linking is aimed at diverting the waters of some of the common rivers to India’s drought-hit regions by linking them with canals.

A Bangladesh parliamentary panel has expressed concern over India’s funding its river-linking project. Bangladesh fears such diversions will affect the flow of the rivers in Bangladesh. India and Bangladesh share 54 common rivers. They have been engaged in disputes over sharing of Ganges water and the Teesta water sharing . The Indian river linking project will add further fuel into the water dispute between the two neighbours.

The Indian mega project of river linking is aimed at diverting the waters of some of the common rivers to India’s drought-hit regions by linking them with canals.

The new BJP government in India , led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, on July 10 allocated 1 billion rupees in his maiden budget with a call for a serious effort regarding river interlinking project to expedite preparations for the Detailed Project Report..

Meanwhile, Bangladesh Parlia-mentary Committee on the Ministry of Water Resources decided at a meeting on Wednesday to seek details of the project from India.

“We have come to know from media that the new government of India allocated Rs 100 crore in budget to bring pace in the river interlinking project which will harm us. We will, therefore, ask the ministry to get clear picture about it,” Romesh Chandra Sen, chief of the Jatiya Sangsad committee told reporters after the meeting at the Jatiya Sangsad.

Terming it a grave concern for Bangladesh’s environment and eco-system, Romesh, a ruling Awami League MP and former water resources minister, also said the committee will request foreign ministry to communicate with India to obtain information about its fresh move regarding the river interlining project.

Originally, the BJP-led NDA government of Atal Bihari Vajpayee in India had mooted the idea of interlinking of rivers to deal with the problem of drought and floods afflicting different parts of India at the same time.

The succeeding Congress-led UPA government could not carry the project forward due to stiff opposition from environmentalist groups, but the Supreme Court, in Feb, 2012, ruled that the government could proceed.

The congress general secretary Rahul Gandhi said in 2009 that the entire idea of interlinking of rivers was dangerous and that he was opposed to interlinking of rivers as it would have "severe" environmental implications. BJP MP Rajiv Pratap Rudy suggested that Gandhi should do some research on the interlinking of rivers and its benefits and then arrive at a conclusion. Jairam Ramesh, a cabinet minister in former UPA government, said the idea of interlinking India's rivers was a "disaster", putting a question mark on the future of the ambitious project.[

Meanwhile environment activists and scholars have questioned the merits of Indian rivers inter-link project. They also question whether the inter-linking project will deliver the benefits of flood control.

Other scholars have suggested to opt for other technologies to address the cycle of droughts and flood havocs, with less uncertainties about potential environmental and ecological impact.

Meanwhile, water storage and distributed reservoirs are likely to displace people - a rehabilitation process that has attracted concern of sociologists and political groups.

Further, the inter-link would create a path for aquatic ecosystems to migrate from one river to another, which in turn may affect the livelihoods of people who rely on fishery as their income.

Indian experts also feared that 50,000 ha of forest to be submerged only by peninsular link. - Intensive irrigation in unsuitable soils will lead to water logging and salinity. - Highly polluted rivers will spread toxicity to other rivers. - River system will be altered catastrophically creating droughts and desert (Holiday, July 18, 2014).

1. 1.Tipaimukh dam

|

Tipaimukh Dam is not an isolated project; it is part of a comprehensive Indian plan of using rivers that flow from India into Bangladesh, and, hence, needs to be viewed in the general context of sharing of international rivers by these two countries.

In general, India has been using its upper riparian position and its economic and financial strength to take unilateral steps with regard to the flow of these international rivers. Most of these unilateral steps have been of diversionary character, diverting the water flow to destinations inside India and thus reducing the flow of water into the rivers of Bangladesh.

Glaring examples of such diversionary interventions are the Farakka Barrage on the Ganges and the Gozaldoba Barrage on the Teesta. India has undertaken numerous other diversionary and flow-controlling structures on most of the 54 rivers shared by Bangladesh and India.

These diversionary projects of India go against the international norms regarding sharing of international rivers. In particular, they violate Bangladesh's right to prior and customary use of river water. The entire economy and life in Bangladesh have evolved on the basis of rivers. Any major change in the flow of these rivers is, therefore, seriously disruptive for Bangladesh. Furthermore, river intervention structures affect the flow of sediments, which are vital for deltaic Bangladesh, which is facing submergence by rising sea level caused by global warming.

First, Bangladesh does not yet have the necessary facts to assess the changes in Barak flow to be caused by Tipaimukh. Second, dams can also be a source of destabilisation, not only in the extreme situation of dam-break, but also in the often recurring situation when the excess water needs to be released to protect the dam from overflow. Such unplanned releases lead to unexpected floods. For example, the unusual 2008 floods in Bihar were caused by unexpected release of water by the dams that India has constructed on the Ganges tributaries near Nepal. Third, for Bangladesh to benefit from stabilisation of the Barak flow, it has to have a say in the release of water at Tipaimukh. This would suggest that Tipaimukh should be under joint control of India and Bangladesh. As of now, Tipaimukh will be entirely under Indian control, and the water release decisions will be made by India alone, putting Bangladesh at the mercy of the Indian officials operating Tipaimukh. Such a helpless situation is not in Bangladesh's interests. Fourth, river flow contains not only water but also sediments, which are very important for deltaic Bangladesh. One damaging impact of Tipaimukh will be reduced sediment volume in the Barak flow. Fifth, Bangladesh has to assess the costs and benefits for her economy of the seasonal changes in the Barak flow caused by Tipaimukh. For example, boro, which is cultivated in the haor areas that become dry in winter, is the main crop for many in the Surma-Kushiara basin. If Tipaimukh increases winter flow, cultivation of boro in these areas may not be possible. Without detailed studies it is difficult to say whether the net economic impact of the cross-season stabilisation of the Barak flow will be positive for Bangladesh. Sixth, there is also the issue of ecology to consider. The flora and fauna of the Surma-Kushiara-Meghna basin have developed on the basis of a certain seasonal pattern of the river flow. Detailed studies are necessary to gauge the environmental and ecological impact of Tipaimukh.

Worldwide experience shows that large-scale interventions in rivers do not prove to be that beneficial in the long run. The hydropower generated often proves to be meagre and costly. The irrigation carried out on the basis of diverted water often proves wasteful and leads to salinity and deterioration of the soil quality, so that diversionary projects end up harming not only the basin from which water is withdrawn but also the area to which water is transported (at a great cost). The reservoir submerges large areas of land, destroying the ecology and displacing thousands of (often most vulnerable) indigenous people, causing permanent problems of alienation and insurgency. The reservoir also becomes a source of methane, undercutting the emission reducing potentiality of the hydropower generated. The reservoir and the upstream flow often become a cesspool of pollution. Dams obstruct sediment flow and the free movement fish stock. While many of the damages prove to the permanent, dams themselves become obsolete due to sedimentation, filling up of the reservoir, etc.

In view of these negative consequences many are now sceptical about dams, barrages and other large-scale river intervention projects. It is an open question whether Tipaimukh dam will be beneficial in the long run and in net terms even for India.

Many in India are opposed to the Tipaimukh dam. They include, indigenous people, state governments of Manipur and Mizoram, environmentalists, river activists, human right advocates, and even economists and social scientists. By providing various monetary benefits and offering free electricity, etc., the North East Electricity Production Company (NEEPCO), the current Tipaimukh implementing agency, has been able to pacify the state governments. However, in India, opposition to Tipaimukh continues.

India should not undertake water diversionary project (such as at Fulertal or at other points) on the Barak river under any circumstances.

India should refrain from water diversionary projects on other rivers shared with Bangladesh.

Bangladesh, India, and the other countries of the sub-continent should abandon the current commercial approach to rivers and to adopt the ecological approach.

Delhi set to build Tipaimukh dam

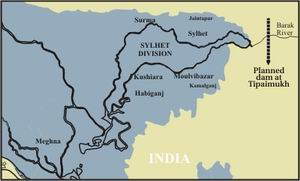

Amidst mounting protests both at home and in lower-riparian Bangladesh, India is going ahead with the plan to construct its largest and most controversial 1500 mw hydro-electric dam project on the river Barak at Tipaimukh on the common borders of three northeastern states of Assam, Manipur and Mizoram.

Officials and experts in Dhaka fear the unilateral Indian move to construct the massive dam and regulate water flow of the Barak, which feeds both the Surma and Kushiara rivers in Sylhet, will have lasting adverse effects on livelihoods, ecology and environment in a vast region of Bangladesh. Moreover, people living in the vicinity of the hydro-electric project in Manipur, costing over 5,000 crore Indian rupee, fear submersion of vast areas on the Indian side too.

Amidst mounting protests both at home and in lower-riparian Bangladesh, India is going ahead with the plan to construct its largest and most controversial 1500 mw hydro-electric dam project on the river Barak at Tipaimukh on the common borders of three northeastern states of Assam, Manipur and Mizoram.

Officials and experts in Dhaka fear the unilateral Indian move to construct the massive dam and regulate water flow of the Barak, which feeds both the Surma and Kushiara rivers in Sylhet, will have lasting adverse effects on livelihoods, ecology and environment in a vast region of Bangladesh. Moreover, people living in the vicinity of the hydro-electric project in Manipur, costing over 5,000 crore Indian rupee, fear submersion of vast areas on the Indian side too.

One of the largest river systems in Bangladesh -- the Meghna with its distributaries -- is fully dependent on the waters rolling down from the Surma and Kushiara. A massive construction on the Barak river will adversely affect the water flows of the Meghna and its distributaries. Against this backdrop, tension is growing over reports that the Indian prime minister laid the foundation stone of the project recently.

Meanwhile, people in greater Sylhet under the banner of Shahjalal Samaj Kalyan Parishad plan to hold a rally at Court Point in the divisional city today, protesting the Tipaimukh project.

In India too, protests have been going on for years in the northeastern region as many people living in the Barak catchment areas fear permanent flooding of their areas due to the impact of the dam.

According to reports from across the border, the Naga Women Union of Manipur protested Manipur State Government's signing of agreement with the North-Eastern Electrical Power Corporation (NEEPCO) for constructing the project. It feared that due to the dam-induced submersion, 15,000 people would be rendered landless and homeless. The Naga People's Movement for Human Rights (NPMHR) also condemned the government decision of constructing the 162.8 metre-high dam.

Bangladesh to issue formal protest against Indian dam project, May 16, 2009

Dhaka - Dhaka will formally protest against New Delhi's plan for construction of a dam which may adversely affect Bangladesh's ecology, after a new government takes over in India, a senior Bangladeshi minister said Saturday. Indian plans for construction of a multi-purpose dam on the Tipaimukh River might cause an ecological catastrophe for its downstream neighbour Bangladesh, Finance Minister AMA Muhith told reporters after a meeting in Dhaka.

He charged that the proposed dam could lead to desertification in the north-eastern region of Sylhet, while also drying up the Surma, Kushiara and Meghna rivers downstream.

"We cannot allow this disaster to take place," the minister said, calling on Bangladeshis to campaign against the Indian project, which has also drawn protests inside India itself.

Bangladesh will send a delegation to visit the project areas after the new Indian government assumed office to see their plan and understand the possible impact.

"We'll solve the problem through bilateral discussion," he said.

In April, Indian Foreign Secretary Shiv Sankar Menon in a surprise visit to Dhaka had requested Bangladesh to send a delegation at the project site to assess the impact of the project in the downstream.

Bangladesh has long asked India to refrain from building the dam, to be located at the confluence of the Barak and Tuivai rivers. India began soliciting international bids for the dam in early 2006.

The Barak River feeds Bangladesh's Surma and Kushiyara rivers in the north-east, eventually flowing into Meghna, one of the three main rivers in Bangladesh.

India plans to complete the project by 2012.

Two senior cabinet ministers, who hail from the region (Sylhet), spoke about their plan to resist the construction of the dam at the Annual General Meeting of Jalalabad Association at Bangladesh Shishu Academy auditorium.

“The dam will desert the greater Sylhet region,” Finance Minister AMA Muhith told the meeting.

He said, the Tipaimukh dam will dry up the rivers Surma, Kushiara and Meghna as well as the haors.

“It’s the responsibility of every citizen to resist the dam,” he said, adding that a plus point is that the Indian people in the surrounding areas of the project like Karimganj and Monipur are also against the project.

Muhith said by implementing the project, India will withdraw waters from international river Barak for irrigation purpose, which will desert the land in Bangladesh’s northeastern region. “We cannot allow this disaster to take place.”(Daily Star, May 16, 2009).

Tipaimukh hydroelectric project

Even as Delhi is all set to begin work on the Tipaimukh hydroelectric project, a multipurpose high dam inclusive, upstream of a major river system of Bangladesh, Dhaka seems oblivious to all relevant developments. Manmohan Singh, the Indian prime minister, is scheduled to lay the foundation stone of the Tipaimukh project on November 23, a source in Indian state of Manipur said quoting chief minister O Ibobi. The Rs 5,163-crore Tipaimukh plan, which has been on the drawing board for nearly 40 years, is set to be built on the river Barak, which bifurcates into two streams as it enters Bangladesh as the rivers Surma and Kushiara.

The Meghna originates at the confluence of the Surma and the Kushiara. Goutam Chakraborty, the state minister for water resources, told New Age Sunday evening that the government did not know anything about the foundation stone laying of the Tipaimukh project.

"Earlier we had protested against implementing the Tipaimukh project through the joint rivers commission of the two countries," he said. "We have requested India to provide detailed information about the project. But they remain taciturn," Goutam said. Secretary to the water resources ministry, Omar Faruque Khan, said, "The government will look into the latest development regarding the Tipaimukh project." The Tipaimukh plant, which was delayed after the Manipur State Assembly had raised objections, has led to protests in India and its downstream neighbour Bangladesh as the project will cause economic, ecological and human catastrophes in both countries.

The residents of the Indian states concerned who are likely to be displaced and affected on account of the project have been staging protests and making representations to their respective state and the union governments, saying that thousands of people will suffer as the construction of the dam will submerge 73 villages, many sacred sites and cultivable land and violate their inalienable human rights. The people of the localities where the dam is proposed to be built have sought constitutional protection, particularly with a view to safeguarding the tribal people, their land, belief, culture and history.

Expressing grave concern over the possible consequences of the dam, the protestors said in a recent memorandum submitted to the central government of India, "Once the dam is built, the land, covering an area of 275.5 sq km, will be submerged permanently." Meanwhile, experts in Bangladesh have expressed their apprehension about the project that is sure to block the flow of the country's major riverine network in the north-east and have further disastrous consequences downstream. They claim that it could hit the country fatally, or have consequences of no less magnitude than the Farakka Barrage across the Ganges to the north-west of Bangladesh (New Age, October 18, 2004)

Tipaimukh to become another Farakka

Dr. Soibam Ibotombi of Dept. of Earth Sciences, Manipur University says that the dam will be a geo-tectonic blunder of international dimensions: The site selected for Tipaimukh project is one of the most active in the entire world, recording at least two major earthquakes of 8+ in the Reichter Scale during the past 50 years. The proposed Tipaimukh HEP is envisaged for construction in one of the most geologically unstable area as the proposed Tipaimukh dam axis falls on a ‘fault line’ potentially active and possible epicenter for major earthquakes

The Tipaimukh Hydroelectric Project is being constructed near the confluence of Barak and Tuivai rivers, in Manipur, India and within 100km of Bangladesh border. Costing Rs 6,351 crore ($1.35 billion) the 164 meter high dam will have a firm generation capacity of 401.25MW of electricity.

The Tipaimukh Hydroelectric Project is being constructed near the confluence of Barak and Tuivai rivers, in Manipur, India and within 100km of Bangladesh border. Costing Rs 6,351 crore ($1.35 billion) the 164 meter high dam will have a firm generation capacity of 401.25MW of electricity.

While Hydroelectric projects are typically considered greener than other power generation options in short term, it has significant long-term impact to the environment like changes in the ecosystem, destroying nearby settlements and changing habitat conditions of people, fish and wildlife. Especially in the densely populated countries like India and Bangladesh, where rivers are lifelines, projects like Tipaimukh will create adverse effect to a huge number of population and their habitats.

No wonder right from the start this project faced protests from potentially affected people in India, and the recommendations of the WCD (World Commission on Dams)”.

The people of Manipur have been fighting legally to stop the project but have so far been unsuccessful. The Indian government is going ahead with the plan. The Sinlung Indigenous People Human Rights Organisation (SIPHRO) of India said that “the process for choosing it (the project premises) ignored both the indigenous people and the recommendations of the WCD (World Commission on Dams)”.

People of Zakiganj yesterday formed a human chain at Amolshid in the upazila protesting Indian move to construct a dam on the river Borak at Tipaimukh in the Indian state of Manipur.

Acid Santrash Nirmul Committee, Sylhet, staged the protest against the controversial dam project, 100-km upstream of eastern border of Sylhet district.

The river Borak bifurcated into two flows and entered Bangladesh as Surma and Kushiyara through Zakiganj border.

Zakiganj Pourasava (municipality) Mayor Iqbal Ahmed and Sylhet City Corporation Councillor Koyes Lodi also joined the human chain programme.

On Friday night, Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers' Association (Bela) organised a discussion in Sylhet city in observance of the World Environment Day.

Chaired by Sushasaner Janya Nagarik Sylhet chapter General Secretary Faruque Mahmud Chowdhury, the speakers

The Indian government initiated the project about a decade ago, but could not go ahead in the face of widespread agitation from its own people at times. Even some 25 peoples' forums like that of Tipaimukh Dam Resistance Committee have been formed there to protest the move. With reference to some experts' opinion, the discussion meeting was told that implementation of the dam project mainly aimed at producing electricity would cause a disastrous situation in the Meghna basin, especially the greater Sylhet and Mymensingh region, during the dry season due to withdrawal of water in the upper stream. Also, they said, there are apprehensions of recurrent flooding during the monsoon due to possible release of water. It will be another Farakka, the speakers said, urging the people to resist the move (Daily Star, June 7, 2009).

India's secretive handling of Tipaimukh dam causing huge concern downstreamIgnoring its promise, India in the last four years has refrained from sharing technical information with Bangladesh about building the Tipaimukh Dam in the bordering Manipur state, triggering public uncertainty and outcry over its possible negative impact on the neighbouring country.

While India has not started construction of Tipaimukh dam on the Barak river near Manipur-Mizoram border, it had floated international tender in 2005 and opened the bid in 2006 during the era of former BNP-Jamaat alliance rule.

INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION AND GANGES WATER SHARING TREATY, 1996According to the International Convention on Joint River Water, without the consent of the downstream river nation no single country alone can control the multi-nation rivers.

But India does not care for these international laws despite being a signatory of this convention.

INDIAN CITIZENS ALSO PROTESTING THE DAMInformation surfaced in different websites says several Indian organisations and civil society bodies are protesting the dam considering its negative impacts.

The websites also say the Expert Appraisal Committee (EAC) of India has found the design of the dam contains many errors, omissions, gaps, lacks in scientific rigour and falls far short of compliance of normative standards set by the scientific and academic community in India and the world.

|

1. 2. India plans to go ahead with river-linking plan, September, 2004

The Congress-led Indian government has decided to implement a controversial river-linking project for unilateral withdrawal of water from trans-boundary rivers despite widespread concern over and protest against the mega-project within India and in Bangladesh. The government will take up the issue for a comprehensive review any time this month, the Indian Supreme Court was reportedly told Monday. Indian solicitor general told the court that the government had decided to continue with the project, the New Delhi-based Times News Network reported Tuesday. The solicitor general told the court that the issue would be placed before the cabinet in September for a 'comprehensive review'. The Indian government sought six weeks time to get back to the court. The case is posted for further hearing eight weeks from now, the Times News Network added.

Dhaka, meanwhile, remains in the dark as the no detail communications have been made by New Delhi since the government of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh assumed office in May this year. The government is, however, aware of the Indian move, Water Resources Secretary Dr M Omar Faruque Khan told New Age Tuesday. "All of us in the lower riparian country should stand together against such a project irrespective of political views as the project may bring about ecological disaster."

Dhaka has already expressed grave concern over the project and called upon New Delhi not to implement it as it is meant for withdrawal of water from the rivers Brahmaputra, the Ganges and Barak, main sources of surface water in Bangladesh, ignoring the interests of other riparian countries. The move in the Indian court came within days of Congress MP Jairam Ramesh's statement that inter-linking of rivers could lead to severe ecological and rehabilitation problems.

"The first requirement for managing floods on a long-term basis in East and North East is a viable, durable water-sharing agreement in the Ganga, Brahmputra and Barak basin involving the states of eastern India, Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh," he said while participating in a recent discussion in Rajya Sabha, the upper house of the Indian Parliament.

"As the river-linking project makes headway, more inter-state and inter-country dissensions are likely to surface," Dr Sudhirendar Sharma, who heads the Delhi-based Ecological Foundation and specialises in water issues, told New Age during his recent visit to Dhaka.

The Indian initiative would be another 'death trap for Bangladesh, even more deadly than Farakka.

According to the initial plan, 37 rivers will be inter-linked to transfer water to regions facing scarcity through 30 links across 9,600 kilometres, connecting 32 dams. Water from the Brahmaputra will flow into the Ganges, which will be connected to the Mahanadi and the Godavari. The Godavari will be linked to the Krishna, then the Pennar and the Cauvery. The Narmada will flow into the Tapi and the Yamuna into the Sabarmati. This huge inter-basin transfer is to be completed by 2016 with an estimated cost of $112 billion (New Age, September 1, 2004).

The concept of “surplus” or “unused” waterThe most important question that needs to be addressed is whether or not there is any “surplus” or “unused” water in Brahmaputra River. The concept of “surplus” or “unused” water is an ironic one. The water that flows in Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (G-B-M) basin is the reason why there exists the deltaic country called Bangladesh to start with. The sediments laid down by these rivers built the delta over millions of years that we call Bangladesh today. Needless to say that there is a very complex ecosystem, including the Sunderbans, that is supported by the freshwater flow in these rivers. Any diversion of water also means proportional diversion of sediments. Any lack of sediment flux to the delta and coastal plains will cause accelerated drowning the coastal region in the face of rising sea-level. In essence, it is already happening due to the impact of Farakka Barrage and will certainly accelerate if other barrages (e.g. the proposed Ganges Barrage, and Mowa Barrage). |

2. China's Move to divert Tibetian Rivers

BEIJING, October 22, 2000 (The Telegraph) -- CHINESE leaders are drawing up plans to use nuclear explosions, in breach of the international test-ban treaty, to blast a tunnel through the Himalayas for the world's biggest hydroelectric plant. The proposed power station is forecast to produce more than twice as much electricity as the controversial Three Gorges Dam being built on the Yangtze river. The project, which also involves diverting Tibetan water to arid regions, is due to begin as soon as construction of the Three Gorges Dam is completed in 2009.

China will have to overcome fierce opposition from neighbouring countries who fear that the scheme could endanger the lives and livelihoods of millions of their people. Critics say that those living downstream would be at the mercy of Chinese dam officials who would be able to flood them or withhold their water supply.

China's state-run media reported that the project would form part of a national strategy to divert water from rivers in the south and west to drought-stricken northern areas. The reports said that a 38 million kilowatt power station at Muotuo on the Yarlung Zangbo river in Tibet would harness the force of a 9,840ft drop in terrain over only a few miles.

The capacity of the station would make it the world's largest power generation facility, much bigger than the 18 million kilowatt plant at the Three Gorges. The cost of drilling the tunnel through Mount Namcha Barwa has not yet been announced, but appears likely to surpass £10 billion.

At the bottom of the tunnel, the water will flow into a new reservoir and then be diverted along more than 500 miles of the Tibetan plateau to the vast, arid areas of Xinjiang region and Gansu province. Beijing wants to use large quantities of the plentiful waters of the south-west to top up the Yellow River basin and assuage mounting discontent over water shortages in 600 cities in northern China.

Yang Yong, a geologist who has explored the river, said the dam could become an embarrassing white elephant amid growing signs that the volume of water flowing in the Yarlung Zangpo could shrink. He said: "Environmental conditions in the upper reaches of the river continue to deteriorate, with glaciers receding and tributaries and lakes going dry." (The Canada Tibet Committee. Issue ID: 00/10/23; October 23, 2000.]

Tibetan activists have warned that the plans are likely to devastate the lower reaches of the Yarlung Zangbo, which flows south where it becomes the Brahmaputra. This river irrigates the northern plains of Assam state in India before flowing through Bangladesh and emptying into the Bay of Bengal (The Canada Tibet Committee. Issue ID: 00/10/23; October 23, 2000.] ).

Large Dams And Local Populations

3. River linking - A Millennium Folly?

Mother of All Projects

Amongst other issues, the book brings into the focus the question of the rights of the riparian countries. Authors assert that riparian rights are not being taken cognizance of and that a unilateral decision by India without a fully consulted prior consent of the concerned countries can injure the already fragile political atmosphere in South Asia (Edited by Medha Patkar,2004) The idea of interlinking of the rivers of India is described by - from the President down to local leaders in the less water endowed areas - as the perfect win-win solution for addressing the twin problems of water scarcity in the western and southern parts of the country and the problem of floods in the eastern and northeastern parts. The claims and statements of politicians, do not, however, substitute comprehensive scientific assessment, so that one can know whether by the proposed interlinking, the right quality and quantity of water would be stored and delivered at the right time in the right places…and all this would be achieved in the most cost-effective manner. For this, what is needed is sound professional assessment of the technical proposals based on the latest interdisciplinary systems knowledge. Unfortunately, as far as the proposal for interlinking is concerned, there is little information available to the open world of science, beyond some lines drawn on the map of the country. Unless the scientific basis and technical details of the proposal are made available for open professional assessment, the justifications that are being propped up for the project will remain mere exercises in the act of guessing on the part of the people, and professing on the part of the water resource officials. Such silence about the technical details of the proposals also has other implications. For example, in contrast with the official prescription for interlinking of rivers, there are strong opinions that India’s water crisis is caused by the mismanagement of water resources and the solutions do not lie in supply side augmentation. Iyer (2000), a former Secretary of Water Resources of the country corroborates this fact, with the view that: Large scale supply side augmentation has been prescribed by the engineers as the only way for the satisfaction of water requirements of the developing countries. As a result, political leaders at all levels have sold the idea of solving the water problem by harnessing the huge monsoon run-off. The reductionist view of engineering is unable to recognise the ecological significance of the unhindered flows in the river as critical to drainage, transportation of sediments, recharge of groundwater, maintenance of the delta and highly productive estuarine ecosystems and related biodiversity. Hence, it finds little difficulty in locating ‘surplus’ river basins! |

4. Disastorous for the Whole Region

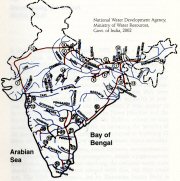

The withdrawl of waterfrom the major rivers will be disastorous for the whole region (Fig):

- Loss of plankton flora and fauna i.e. dramatic decrease of fish in delta front (beyond Sri Lanka).

- No new land will be reclaimed from the Bay of Bengal. The Bengal delta which has been built since millions of years will begin to erode.

- Coastal erosion, saline water intrusion i. e. the upstream water diversion in Bangladesh include saline ingress through the lower Meghna, which could be as far as the haor basin of Sylhet (northeast Bangladesh).

- Almost all cities, industries and agriculture of Ganges-Brahmaputra basin dispose of untreated effluents to rivers. Without fresh water influx a poisonous coctail of biological and inorganic poison will displace ten per cent of global population.

- Flood and tidal storm will displace millions of population.

- The reduction of flows in Atrai, Karatoya and Teesta could spell disaster for the rainfall-deficit Northwestern hydrologic region. Wetland and groundwater recharge capacity would also decrease in the Brahmaputra Dependent Area.

- The decrease in the flow of Brahmaputra (Jamuna) within Bangladesh would adversely affect the flows of the distributaries in the North-Central hydrologic region. The amount of Jamuna water reaching the Ganges at Goalundo would also diminish, thus adversely affecting the distributaries of the South-Central hydrologic region

- Extiction of Sunderbans (Flora and Fauna), the world's largest mangrove forest of the world.

- Unknown ecological disaster as we have very small scientific knowledge on tropical rivers and consequnces due to plate movement (seismic activities) and water withdrawl.

Pollution in the Ganges Brahmaputra Delta Plain

Indian 'Green Lady' and former environment minister Maneka Gandhi was worried that in early 21st century the Indian provinces may be involved in battles due to irrational water sharing.

National Water Development Agency (NWDA) of India to carry out 560,000,000,000,00 Indian rupee (50 Rupees= 1 US Dollar) a project to link 37 rivers through similar number of canals and 32 dams. Indian Prime Minister's personal initiative helped prioritise this project, while the President directed a 'Task Force' in August 2002 to complete the project within 10 years.

India is apparently stressing on the Hormon Doctrine, which originated in the United States in 1895, but has never gained universal acceptance. It is conveniently forgetting various provisions of the Montevideo Declaration of American States (1933), the views of the 1977 UN Water Conference held in Mar del Plata, the decision of the Lake Lanoux Arbitral Tribunal in the dispute between Spain and France and those of legal experts from the International Law Commission.

The Indian plan envisages transfer of water of the Ganges and its tributaries to Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Gujrat. Similarly, it also plans to divert the waters of the Brahmaputra and its tributaries to the Ganges and from there to the Godavori, Krishna, Pennar and Cauvery basins through Subrnarekha in West Bengal and Mahanadi of Orissa.

The Indian plan envisages transfer of water of the Ganges and its tributaries to Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Gujrat. Similarly, it also plans to divert the waters of the Brahmaputra and its tributaries to the Ganges and from there to the Godavori, Krishna, Pennar and Cauvery basins through Subrnarekha in West Bengal and Mahanadi of Orissa.

Again the Brahmaputra and the Teesta would be connected to take waters from the former to the latter and from the latter to the Farakka Barrage. For this purpose they need some 30 connecting canals which (if joined) together would be around 10,000 km in length. Besides nine big and 24 small dams--four of them in collaboration with Bhutan and Nepal--would also be built as required in the master plan.

India also plans to produce 34 million KW (kilowatt) waterpower under the same project. The policymakers, moreover, in India believe this river-link project is worth the huge expenditure as they take the multi-faceted benefits from this project into consideration.

Another thing that added motion to the Indian government's initiatives in materialising the project is a verdict of the Indian Supreme Court. The court verdict, which came after a public interest case was filed with it, ordered the government to realise the project by December 31, 2016. Indian President APJ Abdul Kalam has spoken in favour of this project recently while the BJP govt. has been calling it “Indian's dream project” and promising to materialise it for quite some time now

Notable water expert, Tauhidul Anwar Khan, Member of the Joint River Commission has also very correctly pointed out that India's unilateral move to inter-link the trans-boundary rivers contravenes existing Articles of the 1996 Treaty between Bangladesh and India with regard to the sharing of the Ganges Waters at Farakka. According to him, such a scheme would be contrary to the body and spirit of Articles 2(2) and 9 of this Treaty and would affect providing of due share of common river's water to a co-riparian.

5. Consequences for Bangladesh

Such steps would have disastrous impact on the economy of Bangladesh, its ecology, the livelihood of its people, its eco-system. It will also in the long run lead to internal displacement of millions of its citizens. Specialists have also pointed out that implementation of such a project would most certainly lead to more severe flooding in the monsoon and worse droughts in the lean season. Such vagaries would also contribute to increased salinity across the country and sharp fall in sweet water levels. These factors would juxtapose to eventually destroy the largest mangrove forest in the world, the Sunderbans.

Such steps would have disastrous impact on the economy of Bangladesh, its ecology, the livelihood of its people, its eco-system. It will also in the long run lead to internal displacement of millions of its citizens. Specialists have also pointed out that implementation of such a project would most certainly lead to more severe flooding in the monsoon and worse droughts in the lean season. Such vagaries would also contribute to increased salinity across the country and sharp fall in sweet water levels. These factors would juxtapose to eventually destroy the largest mangrove forest in the world, the Sunderbans.

According to a Washington Times report on September 20, the Indian plan would cause severe flooding during the monsoon rains and worse drought during the dry season in Bangladesh.

Centre for Development and Environment Policy at the Indian Institute of Management in Kolkata as saying that once the Indian plan is implemented, the world could lose the richest fisheries in south Asia. Bandhopadhyaya points out that salinity would also make inroads into the region, affecting thousands of hectares of arable land [and] affecting the lives of millions of people living on agriculture in Bangladesh. Mangrove forests too, he says, will be disastrously affected as they depend on the steady rise and fall of tides for their roots to breathe. Arresting the natural flow of rivers could be a death knell for the world's largest remaining coastal forest a World Heritage site shared by the delta regions of Bangladesh and India.

The wisdom of linking up rivers is not beyond question because more than 70 percent of Indian river water is polluted by linking them and then allowing them to enter into Bangladesh will poison all our water bodies, human beings and wildlife.

The International Law Association (ILA)'s Helsinki rules-1967 and the International Law Commission (ILC)'s second report on the Law of Non-navigational Uses of International Water Courses-1986, both prohibit co-riparian states from altering the flow of an international water course, so as to cause either substantial or appreciable harm to another. Both adopt the equitable balance approach with regards to sharing the waters of an international drainage basin. Similarly, the Salzburg Resolution of the Institute of International Laws in 1961 stated that the right of a sovereign state to use the waters of a shared river is limited by the right of utilisation of other states interested in the same water course. In it's general commentary the ILA states that "Any use of water by a basin state, whether upper or lower, that denies an equitable sharing of uses by a co-basin state/states, conflicts with the community of interests of all basin states, in obtaining the maximum benefit from the common resource. Certainly, a diversion of water that denies a co-basin state an equitable share is in violation of International Law".

While Farakka barrage alone has adversely affected our 40,000,000 (four crore) people of Bangladesh, crippled our agriculture, fisheries, navigation, hydro-morphology, industry, forestry, poultry and other relevant sectors; the Mohanada and the Teesta barrages that were not left uncommissioned by India. By and large Farakka, Mohananda and Teesta barrages together have resulted severe ecological and climatic degradation in Bangladesh resulting in the desertification of the north and north-western parts of the country, destroying the Sunderban forest, the largest mangrove forest of the world, including its flora and fauna, posing serious threat to Mongla Port, and intensifying flood, flash flood, cyclone and draught.

Facing endemic arsenic contamination

According to WHO study, the prevalence of arsenic in drinking water (60mg/1) is much above the permissible limit (0.05mg/1) and this supports the fact that some 80 million people are affected with some degree of arsenic contamination in Bangladesh.

According to WHO study, the prevalence of arsenic in drinking water (60mg/1) is much above the permissible limit (0.05mg/1) and this supports the fact that some 80 million people are affected with some degree of arsenic contamination in Bangladesh.

This monster silent killer is also spreading fast affecting more and more people with the passage of time making it an endemic health problem in the country.

Most of the people depend on tube wells across the country for safe drinking water and this makes them vulnerable to the threat. Most of these tube wells are installed at about 120 feet deep below the surface where the arseno-pirates charged underground water level exists. As a result, people are naturally being affected silently by arsenic drinking water from these tube wells. Safe water from tube wells thus has turned to be a nightmare. People are being affected by painful skin diseases, cancer and gangrene due to long term intake of arsenic contaminated tube well water across the country.Studies suggest that unilateral withdrawal of water from the trans-boundary rivers is causing rivers and canals to die fast. In fact, the North and Southwest part of the country have now turned into a veritable desert. Due to the severe scarcity of water in the dry season the ground water level dropped sharply and that cannot be recharged sufficiently resulting in further drop of underground water level. Pumping out ground water for irrigation and other uses makes the situation worse further.

Experts suggest that tube wells should be reset at 350 feet deep underground to avoid arsenic contaminated underground water level. For a sustainable solution to this problem, the government should put pressure on the neighboring country not to divert water from common rivers unilaterally. It should take initiatives to ensure proper treatment of arsenic related diseases and complications under one umbrella.

A holistic effort needs to be initiated throughout the country to stop downward turn of underground water level.

Mass awareness

through anti-arsenic campaign should also be taken where the media - both print and wire - should play a dominant role (Daily Sun, Editorial,31-03-2014).

5.1 HIlsa Fish (Clupeidae Tenualosa Ilisha)

Imagine a scenario

hundred years from now. The curator of Dhaka Museum is showing a skeletal

remains of Hilsa fish, a recently extinct species, to the visiting school

children. The once glorious novelty and mouth-watering delicacy Hilsa fish

-- a delectable entrée of any common Bengali's dinner -- is completely lost

in oblivion.

Imagine a scenario

hundred years from now. The curator of Dhaka Museum is showing a skeletal

remains of Hilsa fish, a recently extinct species, to the visiting school

children. The once glorious novelty and mouth-watering delicacy Hilsa fish

-- a delectable entrée of any common Bengali's dinner -- is completely lost

in oblivion.  The extinction of Hilsa and a great many other fishes and

aquatic lives would be a fait accompli, if a wrong decision is executed by

the Indian leaders. According to the recent media reports, a grandiose River

Linking Plan is being seriously considered by the ruling BJP leadership of India.

The extinction of Hilsa and a great many other fishes and

aquatic lives would be a fait accompli, if a wrong decision is executed by

the Indian leaders. According to the recent media reports, a grandiose River

Linking Plan is being seriously considered by the ruling BJP leadership of India.

The plan's formal announcement is not yet made. Neither is the detail released to the public domain. The would-be affected neighbouring governments of Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan are ignored and not even consulted. Sifting through the sketchy information from Indian NGOs and western news media, we can sense some aspects of the River Linking Plan and its horrific consequence on India itself and other co-riparian neighbours, especially Bangladesh.

The plan's formal announcement is not yet made. Neither is the detail released to the public domain. The would-be affected neighbouring governments of Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan are ignored and not even consulted. Sifting through the sketchy information from Indian NGOs and western news media, we can sense some aspects of the River Linking Plan and its horrific consequence on India itself and other co-riparian neighbours, especially Bangladesh.

Because of its gargantuan negative consequence on Bangladesh, we should voice our serious concern over this notorious plan and do everything necessary to stop this project. In this article I will address the following questions: what is the project all about and what would be its impact on aquatic life, especially the Hilsa fish of Bangladesh?

Hilsa Clupeidae Tenualosa Ilisha - Bengalis most Favourite Fish

Our mouthwatering Hilsa fish (scientific name: Clupeidae Tenualosa Ilisha) is a rare

anadromous species in tropical water, and it migrates from the Bay of Bengal

upstream about 30-60 miles in Bangladesh for spawning during monsoon and a

short period in winter. Hilsa shad live most of their lives in the Bay of

Bengal.

Our mouthwatering Hilsa fish (scientific name: Clupeidae Tenualosa Ilisha) is a rare

anadromous species in tropical water, and it migrates from the Bay of Bengal

upstream about 30-60 miles in Bangladesh for spawning during monsoon and a

short period in winter. Hilsa shad live most of their lives in the Bay of

Bengal.

They count for almost one-third of fish production of Bangladesh. Approximately three million people's livelihood as fishermen depends on Hilsa. Hilsa eggs are hatched in fresh water at about 73 degrees Fahrenheit. This fish initially feeds on zooplankton, and then on phytoplankton. Large scale impounding of water in upstream lakes and later discharging will lower the temperature in spawning rivers in Bangladesh, thereby hatching will be impeded significantly. The forthcoming controlled structures in the upstream India will increase the silt content, thereby obstructing the spawning migration in Bangladesh.