The Bengalees And Indigenous Groups

CONTENT

- 1. INTRODUCTION

- 2. 2. Ethnic groups

- 3. Chakmas and Marmas

- 4. The Tripura group

- 5. The Moorang group

- 6. The Bawm and Pankhu groups

- 7. The Khiang group

- 8. The Khumi group

- 9. The Lushai group

- 10. Economic activities

- 11. Peace Accord

1. INTRODUCTION

Bangladesh is very much a ethnically and linguistically homogeneous country. Population of this country include the mixtures of ethnic bloods belonging to the genetic admixtures of Mongoloid and Negroid races. The Caucasian, Cymetic bloods in mixture and in pure forms is not uncommon to find amongst the Bangladeshis. However, the racial identities for majority of the Bangladeshis have virtually been mired over the ages forming unified and distinctive Bangladeshi culture except in the cases of several ethnic groups living on hills, uplands and locally in wetland areas of Bangladesh. Many of the ethnic groups living in plain land areas have already been integrated with the main stream of Bengali society both culturally and linguistically while several others are maintaining their linguistic and cultural identities and are now organized for realization of customary rights under their ethnic leadership.

Bangala," the present Bangladesh, has always been an abode for scores of ethnic groups from time immemorial. Besides the Bengali majority people, there are 45 ethnic groups with approximately 2.5 millions (according to the Bangladesh Adivasi Forum) living side by side in this country. With a marked concentration of 11 ethnic groups in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, the rest of the 33 ethnic groups live on plain lands scattered throughout the country. The existence of numerous ethnic groups has enriched the human geography of the region that exhibits cultural and social diversity.

2. Ethnic groups

There exists confusion amongst the anthropologists regarding the actual number of recognizable ethnic groups now living in Bangladesh. Different authorities maintain different views regarding the issue of ethnic groups that varies widely between 12 and 42. However, several groups along with the localities they live are mentioned here:

Baum, Chakma, Khami, Kuki, Banjogi, Riang, Lushai, Marma, Moorang, Mroo, Pankhoo, Rakhain, Tangchungya, Tripura, Khyang, Chak live in the CHT (Chittagong Hill Track) and on hills of Chittagong and Cox’s Bazar districts.

Garo, Marma, Rakhain, Chakma, etc live in Cox’s Bazar, Garo, Hajong, Santal, Koch live in Madhupur Tract and Khashi, Khami, Khyang, Monipuri, etc in greater Sylhet and Santal, Sakh, Hajong, Oraon, Koch, live in the districts of Rajshahi division.

The Harijan and Rajbongshi living in the wetland districts became integrated with the mainstream population and are difficult to recognize. Few Rakhain families live at Kuaghata area of Patuakhali district.

Chittagong Hill Tract (CHT) that cover nearly 1.3 million hectare is situated in the south west part of Bangladesh. Landscape of the CHT being mountainous is altogether diferent from the other parts of Bangladesh. The entire CHT landscape is covered by dense tropical rain forests with unique biodiversities. The highest mountain of CHT has an elevation of 1300 meter. Beside the Bangalees there are 11 other ethnic groups live there. The landscape, vegetation, faunal and ethnic diversities have made the CHT region attractive to the tourists from home and abroad.

The earliest sources of information available regarding the ethnic groups of Bangladesh and of the CHT are from books written by the British colonial rulers in between 1870 to 1909. After occupying the CHT following the Battle of Plasey in 1657 the British rulers attempted finding out the possible means to deal with the ethnic groups of the region. So, information on the socio-cultural life of different ethnic groups was collected and documented in books and in District Gazetteers.

Eleven different ethnic groups with distinctive cultural and linguistic identities live in the CHT.3. Chakmas and Marmas

The largest in respect of population amongst the indigenous groups are- the Chakmas (300,000),

- Marmas (150,000),

- Tripuras (77,000),

- Moorangs (30,000) and

- Tangchuingas (25,000).

The smaller groups e.g Kuki, Lushai, Mizo, Banjogi, Rakhain,Khiang, Chak, etc. constitute remainder of the 6,00,000 indigenous population now living in the CHT region. The Bengali population in CHT counts over 700,000.

According to the available records it is evident that the Kukis and Mizos migrated in the CHT in the early 15th. century. Movement of ethnic tribes at that time caused due to crop failure, being defeated in intertribal and intratribal conflicts, for occupation of conquered land, etc. The Chakma and Marma groups entered in the CHT in comparatively recent years compared to the Kukis and Mijos probably being ousted from the Arakan State by the Arakanese. The Chakmas entering in the CHT defeated the Kukis and pushed them toward the north-east region. Marma group migrated in the CHT almost simultaneously with the Chakma group from Myanmer because of the above reasons. Several ethnic tribes now live in the CHT region are discussed briefly in this article to figure out their overall social and cultural structures.

Chakmas the dominant ethnic group migrated in CHT from Arakan under protection of the Arakanese king probably during the early 15th century. Excepting in the Bandarban district Chakma group constitute majority all over the CHT region. The most recent written records and in the history of Chakmas in CHT it is not clear enough to avoid varying assumptions regarding their stay.

Arakanese origin of the Chakmas become evident from the fact that they speak in Arakanese mixed Chittagonian Bangla with a written script of Arakanese variant characters. They live scattered throughout the CHT on hill, in valleys, towns and growth centres. The Tonchuingya group are similar to that of Chakma group in racial origin, language, history and culture except that they live on the high hills of Kaptai, Belaichhari, Rajasthali and Rangamati areas.

The Chakma royal family claims to have descended from a Kshatriya prince who migrated from the Kalapanagar an ancient city at Himalayan foothill now in Myanmar. They fought many battles with the Arakanese during the 12th and 13th centuries and with Muslims in the north subsequently. During the early 15th century Chakma group ousted from the Arakan was granted shelter at Alikadam, Ramu and Teknaf areas by a Chittagonian ruler.

The British East India Company appointed the Chakma king as Chief of an area for collection of revenue from the users of land like that of the Zaminders in plain lands. The British rulers in 1873 compelled the Chakma chief to live at Rangamati amongst his subjects instead of living at Rajanagar in seclusion.

The Chakma group in general believe in Buddism as faith. They have many clans that are oath bound to help each other to build a strong fraternal relationship amongst the clans. Each Chakma clan has a Dewan who is assisted by Khishas for collection of revenue. Chakmas are used to arranged marriage and allow inter clan marriage when no visible relationship exists between them. The marriage is solemnized by tying a long cloth (jargot) around the waist of the bride and bridegroom. The couple feeds each other a morsel of cooked rice at tied state.

The marriage is complete after loosening of the jargot. Elders of the family and clan then bless the newly wed-couple. They burn the dead in riverbank after observing six days of mourning. The relatives of the dead during the mourning days refrain from taking meat or fish. On the seventh day they visit the cremation site and lay full meal to the dead there.

The Marma group is second biggest in population in CHT living mostly in Bandarban and Khagrachari districts. They are divided into Northern Mong and Southern Mong Circles in CHT. The Myanmer invaders drove the Northern Mongs belonging to the Palengsa clan from Arakan during late 18th century. Initially they settled at Cox’s Bazar and Sitakunda areas and moved to the present locations in the early 19th century after the East India Company initiated a cotton farm there for the Myanmar immigrants.

The Southern Mongs belonged to the Regrayesa clan migrated in CHT earlier then the Palengsa clan. They claim to have migrated with the prince of Pegu in 1599 when the Myanmar ruler occupied Pegu with the support of Arakanese king and took with him the princes, a prince and 30,000 talaiang followers of Pegu prince. The Arakanese king later married the princes of Pegu and sent the prince as ruler of Chittagong in 1614 AD. The Pegu Prince Maung Shaw Ryne ruled Chittagong, Noakhali and Bakerganj until he was pushed back by the Portuguese invaders in 1620 leaving the prince to take rule over the Bohmong Circle only.

The Mughals in 1666 conquered the region ending the Arakanese rule in Chittagong. Despite the defeat most of Talaiang people continued staying in CHT while the king Bohamong Gee did flee to Arakan to returned back to CHT and settled at Bandarban hearing defeat of the Moghuls to the British in 1858 after the Shipahi mutiny taking over control of the CHT.Marma group

The Marma group have the language called Maghi a Arakanese-Mganmarian dialect written in Myanmarian characters. They consider Myanmer as centre of cultural life. The Marma women wear blouse and men wear dark coloured loincloth. They maintain patriarchal family structure. Marmas belive in Buddism. Male members of the clan arrange marriages amongst the Marma groups where the girls’ consent is considered important in marriage solemnization. Pre-marital courtship in Marma groups is allowed. They burn the dead keeping the corps for seven days to mourn a death.

4.The Tripura group

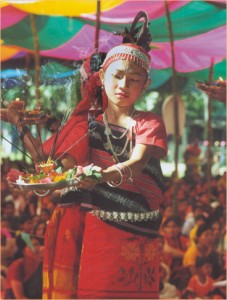

The Tripura groups are scattered throughout the CHT with relatively dense population in Khagrachari district. They migrated from the Bordo area of Assam and from Tripura state. The Tripura group migrated in CHT following a religious conflict between the Kshatriya king of Tripura state and their group and during the war between the Mughals and Arakanese. The Tripuras claim to be the most ancient immigrants in the region claiming their origin since 600 BC. They had their prime during the early 13th century when the Tripuras controlled entire Chittagong division. Tripura state was subsequently overrun by the Mughals in 1773 after a long war and was controlled by the British East India Company in 1816. There are nearly 36 clans amongst the Tripuras group of which only 8 live in Bangladesh. The Ushai clan predominate at Bandarban while the Riang clan dominate elsewhere. The women in the Tripura group enjoy little right in the male dominated families. Marriage is arranged and intermarriage amongst clans is permitted. They burn their dead like that of Hindus. In recent years nearly 30 percent Tripuras embraced Christianism. The women wear the home-spun khamis while the men wear dhotis. They speak in Hallami and consider the dialect as their own.

5. The Moorang group

The Moorang group migrated in the CHT from the Arakan state being ousted by the Khumis during the early 18th century. They resemble the Mongoloid characters only in traces and speak in a Tibeto-Myanmarian language. The Moorang group live on remote eastern slope of high hills in Bandarban district with dense concentration in Chimbuk , Lama, Kankabati and like areas.

The Moorang tribe has five clans and the designations are derived from different plant species.

Moorangs are animist in faith believing in an universal spirit called Turai though Orang is the most respected spirit of the Moorang group. They have no priest hence the religious rituals are performed by themselves. They blame the cows for being deprived of a formal religion by them. They, according to sayings believe God once called their leader to bring the formal religion like the other groups. The leader at that time was too busy in Jhum to respond to the call of God. So, a cow was sent in his place to bring religion from the God. The divine scripture handed over to the cow was written on a banana leaf. The cow on its way back became tired and hungry and at a stage eaten up the banana leaf thus making the Moorangs devoid of any formal religion. In retaliation to this sad incident the Moorang group kill a cow through a festival called Kumlang or Shachiakum after the autumn harvest each year. The Moorang houses are unique in architectural design with bedrooms, living room. cooking place and spacious burenda. The houses are constructed with huge quantity of bamboo, timber and thatching grass.

The Moorangs love music, song and romance. The pre-marital courtship amongst young boys and girls is permitted amongst the Moorangs. When a couple finally decides to marry the boy pretends as if he has eloped the girl hiding with the girl inside deep forest. After hiding of the couple the entire community immediately initiate a search in the forest throughout the night to find them. The mock search results in a failure usually. The couple come out of hiding next morning as victorious and elders in the community settle their marriage fixing a dowry payable to the father of the girl in silver coins. The formalities are completed with the provision of a grand feast. The Moorang group burn their dead in a festive ceremony killing cattle and hang the head bone of the cows at burning place near the chharas. The larger the number of bones hanged is more prestigious to the dead and the family.

6. The Bawm and Pankhu

The Bawm and Pankhu are the small ethnic groups living at Kaptai, Sajek, Ruma and Rowangchhari thanas. These groups claim their origins on the southern slope of the Chin-hills in Myanmar and Zau plateau region in the Arakan. They migrated to the CHT being ousted from Myanmar by the Khumis. Bawm and Pankhu groups still retain their original vicdict of maintaining hostility with the Buddists. Most of their worships are directed to the “Khozing” considered as the patron of the tribe and ruler over the Jhum and forests. In recent years the Bowm and Pankhu groups have become Christians being converted by the western Missionaries. They have their own languages that are written with Roman script provided by Christian Missionaries.

Marriage in these groups is solemnized through courtship between the couple but with the consent of parents. Women are mostly elder than men at the time of marriage and the later dominates the family. They bury their dead with no formal mourning.

7. The Khiang group

The Khiang group live in Ruma, Thanchi, Rowangchhari and Bandarbon region. This group migrated in CHT during the 18th Century after the Myanmer king conquered Arakan state. Their language is related to the southern Chin language in Myanmer.

The burn their dead like the Hindus. They are animist by but are presently influenced greatly toward the Buddhism. The Chaks live in Naikhongchhari migrated from the Arakan state. Culturally they resemble to the Chakma group to a great extent.

8. The Khumi group

The Khumi group migrated in CHT from the Kaladar river basin of Arakan hill area. They claim that the migration in CHT occurred during the 17th century along with the Moorong, Marma and Shendhu groups. They speak in a dialect closely resembling the Moorang dialect. This dialect as per their claim maintains purity not being influenced by other dialects. Khumis though have 22 clans of which only two live in the CHT. The Khumis are oath bound to help the clans though they are ill-famed for militant habits and inherent jealousy to the other groups but are proud remembering that they compelled the Moorang, Bawm, Pankhu and Shendu groups from the Arakan state in the past.

The original faith of Khumis resembles to the faiths belonged by Pankhu, Banjugi, Lushai and Khiang groups. Marriage customs of this group encourage free mixing and pre-marital courtship amongst men and women. They do not allow marriage within same clan like the Moorang group. The Khumi women usually wear a 12 cm wie home-spun khami keeping the upper part uncovered like the Moorang women. They burn the dead and bones of dead are collected and stored in a small house made for the purpose within a community.

9. The Lushai group

The Lushai group live in the Sajek valley of Baghaichhari thana. They are in fact Mizos who crossed over the Lushai hill to migrate to the CHT. The Lushai group were ill famed for their tribal feud, head hunting and lunching raids on Christianity. The Lushai language is now written using Romanised script introduced by Christian Missionaries.

The Lushais chose the bride themselves and arranged marriages are rare in the group. They are now largely Christians and the Church is the main social institution around which the socio-cultural activities rotate.

10. Economic activities

The natural resources of the CHT include

- RF (274,155 hectare),

- USF (339,859 hectare),

- PF (7,968 hectare) and

- Plantation Forest (82,156 hectare).

- Total area of inland water including the Kaptai lake area available for fisheries is 89,737 hectare.

In addition there remains enormous scope for development of horticulture, ethno-botanical plant species, medicinal plant species, cultivation of can, bamboo and few other plant species as industrial raw materials raw materials, etc. Management of wildlife species that include 116 mammals, 578 birds and 124 reptiles both in the plantation and natural forests can also be highly paying for the CHT people and for the nation at large. Greatest prospect of the CHT in fact lies in the proper development of tourists industries. The ecological and ethnological diversities, the mountainous terrain, the artificial lake can be capitalized for enhancing development of tourists’ industry in CHT. The vicinity to the largest seaport of the country and to the Cox’sbazar sea beach is the additional advantage for development of tourists’ industry in the region. It is also likely to have a big hydrocarbon potential (Anwar, 1980).

The CHT area being a flood calamity free zone can be utilized for cultivation of novelty crops like baby corn, onion, melons, guava, papya, lemon, citruses, good quality banans and various vegetable species through organic farming for marketing to the international ships touching the Chittagong port. This will no doubt require development of proper cultivation method, authentic certification of quality, standard packaging and establishment of linkage with the international markets through reputed and dependable agencies.

But what is required to be done urgently at the moment for developing and managing the biological, physical and cultural resources of CHT properly and scientifically. Development of the CHT resources and to harness optimum benefits from such investment the CHT should be an open and safe for the national and international tourists and for the local ethnic groups. All concerned stakeholders can achieve this through restoration of peace in the region through implementation of the Peace Accord in just manners instead of creating issues for bargaining. A long time has been past since signing of the Peace Accord adopting the policy of no compromise by the stakeholders. This has not only delayed advancement of the region to the detriment of peoples’ interest but also proved discouraging to the donors already. Hence, it is high time for all concerned to realize the reality and to initiate fruitful discussion to resolve the difference that might exist between them. Unless the local resources including human resources are fully mobilized the overall poverty of ethnic groups in the region cannot be alleviated. Ethnic distrust that recently developed in the region is an outcome of severe poverty that engulfed the CHT mainly due to eco-degradation amongst several other regions (Dr. Mir Muhammad Hassan , August 27 2006). Apparently most of the ethnic groups look alike in their physical appearance, traditional apparel, habits and overall living conditions and surroundings. But the differences amongst the ethnic groups whatever minor may be are recognizable by CHT people and by the specialists. The do not like coexistence of other ethnic groups and of being dominated by another tribe. Several ethnic groups e.g. Moorang, Pankhu, Khumi, Kuki, Tangchuinga, etc prefer moving to the remote places if their villages become exposed to easy excel due to road construction. This may a reason why they are still deprived of civic facilities e.g. water supply, heath and sanitation, education, marketing of products, etc.

The CHT region though has very high potential for forestry, horticulture and tourism development despite that the ethnic groups including the settlers from plain land live below the poverty line. High population growth rate by new birth, migration of plain land settlers and floating squatters have adverse impacts on the resource potentials of the CHT. The apparent population density of CHT (±60 persom/km2) though is thin. This is because area of arable land in CHT is less than 4.0 percent of the total land area.

Jhum cultivation

The economic activities in CHT to which the indigenous groups involved are Jhum cultivation on hill slopes, sedentary agriculture in valleys, horticultural plantation, forestry activities, plantations of industrial crops e.g. tea, rubber, medicinal plant, etc. Other off-farm activities include fishing in Kaptai lake, labour in transport industry, handicraft manufacturing using bamboo, cane and wood, furniture factories, small trading, weaving, tourism related activities, etc. Share of the indigenous communities in the economic activities of the CHT excepting Jhum cultivation may not be proportionate to the population percentage they occupy.

The big industries like the Kaptai Hydel Power project, Forestry development projects, Karnafuli Paper Mills, Karnafuli Rayon Mills, etc. and other forestbased industries are not healthy enough to benefit the local people adequately. The indigenous communities of the CHT are not also in favour these industries because they find little benefit for them in those industries that occupied large chunks of their Jhum lands.

11. Peace Accord

The CHT area since past three decades turned to a politically unstable region due to racial distrust developed between the Bengalees and indigenous groups under Chakma leadeship that resulted in armed conflict between the government force and CHTJSS force initiated by M.N. Larma supporters. The conflict continued unabated until the Peace Accord was signed in February 7, 1997 between GoB and CHTJSS lead by Shantu Larma. Though 10, years passed already since then but the CHTJSS leadership is totally unhappy on the progress made so far toward implementation of the Peace Accord and blame the GoB for the failures. GoB on the other hand claims its big success toward implementation of the Peace Accord.

The greats hurdle that exists between the two parties despite the different claims in complete implementation of Peace Accord is no doubt the land settlement issue and withdrawal of army from the CHT.

The Land Commission formed by the GoB for resolving the land issues can claim little success so far to resolve the land issue to the satisfaction of settlers and of the indigenous people. Unlike in the plain land areas the use right of land in CHT particularly for the indigenous groups is determined by customary right than by title documents.

The DCs of CHT districts on recommendation of Headmen and tribal Chiefs are empowered to lease the Khash land to an individual belonging to the indigenous community for a specified period for settlement, agriculture and for other types of uses. Under the CHT Act of 1900 no plain land people were allowed buying land in the CHT. But Section 34 of the CHT Act has been amended in 1979 to permit settlement of plain land people despite vehement opposition from the indigenous groups. And following that amendment nearly 5,00,000 refugees from plain land have been settled on CHT land sometime in complete defiance of customary right of the indigenous groups. This has pushed the ethnic distrust virtually to the point of no return. Presently the land occupancy in CHT is classed as owned, leased, khash and non-specified. The settlers in most case have lease documents in their possession while the indigenous groups occupying the land through generations have no title document in possession except in the Registrar of Headmen that in reality is the ill-maintained documents. Moreover, the situation has aggravated further due to the negligence of Land Ministry, corruption of officers as individual and politicisation of land issue since past three decades. The natural resources of the CHT depleted rapidly reaching to the bottom level because of the above factors within three decades.

The BNP- Jamat regime that vehemently opposed signing of the Peace Accord by the AL regime pursued a policy of sitting idle on it. This has not only widened the gap between the government and CHTJSS leadership but also generated distrust of the indigenous groups both on CHTJSS and GoB leadership. The situation again has almost reached to the breaking point e.g. worse ever since signing of the Peace Accord. Hence, a third force might appear in the scene any moment that may not be palatable to either of the concerned parties presently involved.

It is a pity to mention that most people controlling the country including the enlightened public know little if at all regarding their live style, joys and sorrows of nearly 1.5 million indigenous people of our country living in remote areas. Consequently they feel that they are being exploited ruthlessly by the vested interests those are not untrue fully. Most people in Dhaka because of their total ignorance think that CHT is the resident of Chakmas and Moghs who are just wild races are fighting the Bangladesh army on flimsy or no genuine grounds. So, preferred a military solution of the problem that failed since the past three decades. It is stated here that 11 indigenous communities living in CHT are not manning the Shanti Bahiny. Marmas and Tripuras definitely are not very willing participants in Shanti Bahiny because of their internal feud with the Chakmas while the smaller groups e.g. Moorang, Kuki, Khumi, Banjogi etc. are neither very much acquainted regarding the Shanti Bahiny nor they prefer a Chakma domination on then in the CHT. The rights of all the smaller ethnic groups and the exiting century old tribal feud amongst the ethnic groups deserve consideration in dealing with all issues reached in consensus between the Chakma dominant CHTJSS and GoB for implementing the Peace Accord to ensure lasting peace. The issue of 5,00,00 plain land settlers definitely comes in picture particularly in dealing with the land issue, the crux of the problem since 1980. The task of resolving the land settlement issue taking all the factors in consideration may not be that easy hence would require time for dealing as a continuous process.

The country's constitution, framed in 1972, is the proof of such willful negation of the right to be different. It has had policy implications on ethnic groups as a whole. Initially there had been a forceful demand from the ruling regime that the ethnic groups in the country should accept "Bangalism" as their identity. This ideological posture contradicts the historical language movement of 1952 and then the liberation war in 1971, fought in the name of the recognition of Bengali identity as a language and as culturally different. The historic opportunity for an harmonious multi-cultural Bangladesh was lost and set the stage for three decades of struggle. The subsequent history of the country is a testimony of the immediate backlashes of this policy adoption.

Rights of adivasis have been denied

Mr. Manabendra Narayan Larma, the then sole MP from the Jummas of Chittagong Hill Tracts protested the move for framing the country's constitution on a single nationality. He insisted that the constitution should be based on multi-ethnicity. He demanded that the adivasis have rights to be different with distinct cultures, customs, history, traditions and they are not Bengalis His demand was forcefully turned down. The result was the formation of the Shantibahini and the struggle for autonomy by the Jummas in the Chittagong Hill region lasting for almost three decades. The struggle was concluded through a peace treaty in 1997 led by Joyotiridra Bhudipriya Larma, Chairman, Parbataya Chattagram Jana Sanhati Samity

Garos and Hajongs who were freedom fighters earlier in 1971 (90 percent of Garos, Koch, and Hajongs residing along the border of greater Mymensingh had to take refuge in India during the liberation. Hundreds of them joined freedom struggle). Being frustrated for the willful ignorance of their sacrifice and contributions to the 1971 liberation war, they justified joining the 1975 insurgency as an opportunity to promote their rights.

It is indeed a paradox that the nation imbued with an ideology of nationalism would adopt a hegemonistic attitude towards other nationalities in the country. A chance for the development of multi-ethnic and multi-cultural society was missed. Consequently in many cases the rights of adivasis have been denied -- such as in the case of the Modhupur Forest where century-old roads are blocked with 6 feet high brick walls, ancestral lands taken, livelihood bases robbed -- and all these are done without discussion and consultation. Modhupur National park will be built for providing recreational facilities for the affluent middle class of Dhaka.

Demands of ethnic groups are vibrant and grow stronger. The voice that was raised in 1972 for equality, fraternity and for constitutional recognition still vibrates in the depths of indigenous people's minds, in the murmuring forests and alleys of hills where they live, and it is getting louder and is trumpeting in the streets of the capital. It is time policy makers and the people of good-will in the country open their ears and eyes to the rightful demands of 45 ethnic communities numbering almost 2.5 million. It is encouraging to see that thousands of voices from the mainstream Bengalis -- printed media and civil society groups, are raised in support of the ethnic communities and their rightful demands (Albert Mankin, a Garo, heads CIPRAD (Centre for Indigenous Peoples Research and Development) and is vice-chairman of Bangladesh Adivasi Forum, August 9, 2004).

Indigenous cultures certainly enrich us in various ways. And they have great potentials to contribute to the national development process through their proven virtuosity in different crafts. But they have been complaining of certain infringements on their lives which cannot be trifled with. Land grabbing and impingement on their habitats are two of their major concerns. The decision to turn a big area in Modhupur, inhabited by the Garos, into an eco-park has had an adverse effect on their lives. They feel intimidated and threatened. They are being pushed to the sidelines as the encroachment on their lives is getting more and more unmanageable. If we sincerely want them to be mainstreamed, then this is not the way to go.