5. CULTURAL AND FOLKLORE HERITAGE

Tagore patronised others and he himself collected a large

number of folklore materials from his vast estate of East Bengal,

including Bangladesh. He himself wrote : "When I was at Selaidah, I

would always keep close contact with the Bauls (mystic folk singers)

and have discussion with them, and it was fact that I infused tunes

of Baul songs into many of my own songs".

Many people say

that 'Tagore used numerous folklore themes in many of his poems,

songs, dramas, novels and short stories. Other scholars, who made

important contribution to folklore were Upendra Kishore Roy

Choudhury : Toontooni Pal (1910 Book on Toontooni) and Mitra Majumder

Takore: Thakur Mar Jhuli (1906 Grandmother Stories), Monsur Uddin

(collector of Baul songs), Jashim Uddin (who was famous for his

folklore themes in dramas and poetries).

The third phase of folklore movement began in Dhaka, then East

Bengal, in the year 1938, when the Eastern Mymensingh Literary

Society was established. This promoted the collection and study of

folklore. Folklore activities were, however, much accelerated when

the then government established the Bangla Academy in Dhaka in 1955

to promote research work on Bengali language and literature and

collected, preserved and published folklore materials. Folklore

candidates, appointed by the academy, worked in regions rich in

folklore. As a result, folklore materials of high quality poured in

on an unending stream. So far, the Bangla Academy has published many

books on folklore.

Bengali ballads which are called Gatha or Geetika in Bengali are

one of the earliest variety of folksongs. The dates of origin of

Bengali ballads will safely go to up to the Middle Ages, if not

earlier. Divergent opinions have been expressed as to the origin of

ballads. There are two contending groups : (1) communalistic, and (2)

individualistic.

The first group saw in ballads a continuing traditions from the

primitive ages and thought that these were made by a kind of communal

improvisations for communal recreation. Later, critic suggested that

people were too indefinite, too disorganised for such concerted

efforts, and that ballads were composed under the direction of a

leader who brought the necessary discipline in songs and who

functioned as the main organiser and guide.

According to the critics,

after an individual ballad was composed, it passed on from people to

people, community to community through oral traditions. In the

process some were changed, improved and sometimes even deteriorated.

This individualistic theory has been accepted by the scholars at both

home and abroad.

Behind ever art is a man, behind the man is the race and behind

the race is the social and natural environment and these influences

are sure to be reflected on folklore. Bengali ballads give us an idea

of the Bengali society in the Middle Ages, its joy and sorrows,

laughter and tears. Bangladesh is the land of rivers -- almost all

villages are linked with rivers. There is a proverb which

says, "There is not a single village without a river or a rivulet and

a folk poet or a minstrel".

The struggle for existence was not as hard in Middle Ages as it

is today and the minstrels and folk poets had ample opportunity to

enjoy nature and pass care-free-time in composing songs and stories.

Moreover, they were always patronised by the local feudal lords.

It was, of course, Islam that gave the highest acceleration to

the development of the Bengali ballads. The Turks conquered Bengal at

the beginning of the 13th century. Muslims brought with them a huge

store of Persian literature.

The low-caste Hindus for the first time

in their life had the opportunity to talk and mix with the conquering

race. They saw that there were no barriers to caste and creed among

Muslims and that all men were equal in Islam. In due course, the

influence of the Persian romances reached the remote corner of the

country. Gradually, the Hindu society also came to know of this and

humanism like the south wind blew over the literature of Bengal. Even

though these stories and songs were composed earlier, they were

unfortunately collected from the oral tradition only by the second

decade of the 20th century. It is quite obvious that these stories

underwent a great change.

Earlier the poets were patronised by the

feudal lords, but in the later period probably when the poets lost

their patrons in the British period, they became the "property of the

masses rather than the classes". May be, for this reason the quality

of the folk stories and songs, composed in the later period,

deteriorated.

Many stories and songs have been collected till now. The ballads

are usually sung in accompaniment with tabors, drums, and other folk

instruments. Ballad stories are sung by a leader who is

called "Gayen' and he has a group of associate singers called 'Paile'

who join in the chorus in illustrating the episodes.

There are innumerable varieties of folk songs in the riverine

Bangladesh which are sung by different cultural groups in different

parts of the country. The most popular variety of songs can be

divided into many different classes.

The first class of songs can be divided into "Work songs"

or "Occupational songs". These songs include harvest songs, which are

sung at the time of harvest or cultivation; songs of the bullockcart

drivers or palan-quin-bearers sung at the time of carrying passengers

from one place to another; songs sung by labourers when they built

roofs of a house; 'sari-gaan', sung by boatmen in the month of

monsoon, at the time of boat race, etc.

Both Kavi and Jari sometimes go beyond the limit of their

particular subject and in the course of singing introduces modern

topics or amusing national and local events. Sometimes when ritual

singers indulge in personal attacks through the exchange of sharp

wits, the audience bursts into laughter.

We see that all the folk

songs and stories of Bangladesh inform us about the then society. It

depicts clearly how the people used to think, their customs, and what

the principles they used to follow. Through all the folk materials

collected over the years we can learn more about our country's

history and tradition. We learn that Bangladesh has rich cultural and

folklore heritage, which may be compared with any other country of

the world rich in folklore. Since folklore has already been accepted

as a social, cultural and ethnic study, Bangladeshi Folklore will

also have a distinct place in the study.

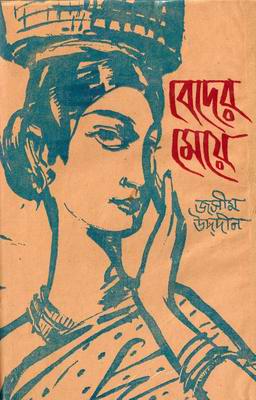

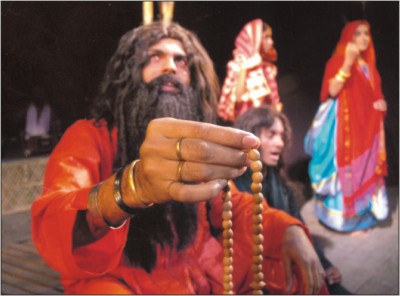

Bedermeye- - Jasim Uddin's famous musical and drama on oppressed and neglected gypsy folk: Part I

Bedermeye- - Jasim Uddin's famous musical and drama on oppressed and neglected gypsy folk: Part 2

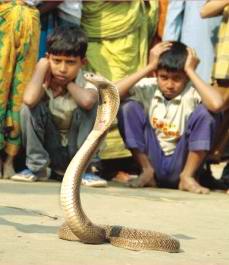

Snake Charmer / Babu Selam Lyric and Music Jasim Uddin, dance by Shibli & Nipa

Babu Selam Bare Bar A gypsy song Music and Lyrics by Jasim Uddin

O babu, many salams to you

my name is Goya the Snakecharmer,

My home is the Padma river.

We catch birds

we live on birds

There is no end to our happiness,

For we trade,

With the jewel on the Cobra's head.

"We cook on one bank,

We eat at another

We have no homes,

The whole world is our home,

All men are our brothers

We look for them

In every door….."

(Jasim Uddin)

Bangladesh snake charmers

Bangladesh has an estimated 500,000 snake charmers, who rove the country like gypsies or live in riverboats.

Some 5,000 have settled with their families in Porabari village, 32 km (20 miles) from Dhaka, where every household boasts a basket full of snakes, even though few charmers are teaching their children their art. Bangladesh has an estimated 500,000 snake charmers, who rove the country like gypsies or live in riverboats.

Some 5,000 have settled with their families in Porabari village, 32 km (20 miles) from Dhaka, where every household boasts a basket full of snakes, even though few charmers are teaching their children their art.

"This is not because we no longer love snakes or dislike to play them for a living," said Alamgir Hossain, 45, who holds the title of "sorporaj" or "snake king", the highest honor in the community.

"I grew up with the snakes, played with cobras, and, maybe you can say, romanced with them," said the father of six.

"So did most members of the clan. They play snakes to crowds of villagers for money. But those days have changed."

Now many of Porabari's charmers have taken other professions with more predictable incomes, like pulling rickshaws or growing rice and vegetables. Most send their children to school.

Urbanization, deforestation and other environmental changes have also decreased Bangladesh's snake population. Even though the government has banned the killing of snakes, villagers often kill serpents that have bitten or killed others.

Hossain won his title after many years of devotion, practice and training in Bangladesh and India's Assam state. Today, few have the patience or inclination to do the same.

He said he was one of only six living "sorporaj" in the country -- five of his predecessors were killed by snake bites.

In Porabari, children play with snakes without fear, draping them around their necks like garlands.

Female snake charmers often sell talismans and "medical" advice to illiterate villagers. Male charmers are often called upon to cure people who have been bitten by poisonous snakes and are seen as "ujhas" or paramedics.

Hossain said Porabari's charmers make most of their money from selling snakes to the other charmers who descend on the village for the weekly snake market.

"I try to buy nearly 100 snakes in each consignment, for 400 or 500 taka ($6-7) each, and then sell them for a minimum profit," Hossain said. "But high quality snakes, like the king cobra, are rarely found and cost nearly 5,000 taka a piece." Hossain said Porabari's charmers make most of their money from selling snakes to the other charmers who descend on the village for the weekly snake market.

"I try to buy nearly 100 snakes in each consignment, for 400 or 500 taka ($6-7) each, and then sell them for a minimum profit," Hossain said. "But high quality snakes, like the king cobra, are rarely found and cost nearly 5,000 taka a piece."

Despite his elevated position in the community, Hossain said he had no intention to allow his children to follow in his "risky" footsteps.

"But we cannot live without snakes," he said. "We love them like we love our children."(Masud Karim, Reuter, June, 1, 2007)

($1=69 taka)

Members of a bede (river gypsy) community show a cobra spreading its hood at a human chain rally jointly organised by the community and Grambangla Unnayan Committee at Shahbag in the city yesterday. The rally was held to press home the demand of education for gypsies' children. Members of a bede (river gypsy) community show a cobra spreading its hood at a human chain rally jointly organised by the community and Grambangla Unnayan Committee at Shahbag in the city yesterday. The rally was held to press home the demand of education for gypsies' children.

Although in most Bangladeshi villages there is some local snake charmer, the main snake artistes, however, are the wandering snake charmers of Bangladesh, the Bedes. It turns out, there are three types of sub-professions within the Bedes. The groups are “Shapure”, “Sowdagar” and “Misisganni”. The group that is most heard of, of course are the Shapures. Some of these Shapures make their living by catching and selling snakes. Other Shapures train their snakes a range of tricks so that they can become entertainers.

Nowadays, snake charmers are far less prevalent in Bangladesh than they were before, and this is not surprising. Even though their numbers of dwindling, plenty of professional snake charmers can still be found around the Bangshi river in Savar, the Dhaleswari in Munshiganj and the Padma.

A gripping saga

Palli Kabi Jasim Uddin's "Beder Meye" staged

Padatik Natya Sangsad staged Palli Kabi Jasim Uddin's timeless tale Beder Meye at Bangladesh Mahila Samity Auditorium recently. The play is directed by Irene Parvin Lopa.

As the title implies, the play is the saga of a bede girl. Named Champabati, her life changes forever when she is abducted by the morol (village headman). Despite fervent appeals, her husband (Gaya), fails to rescue her. He then leaves the village and marries another girl. Subsequent events lead to a dramatic denouement. Padatik Natya Sangsad staged Palli Kabi Jasim Uddin's timeless tale Beder Meye at Bangladesh Mahila Samity Auditorium recently. The play is directed by Irene Parvin Lopa.

As the title implies, the play is the saga of a bede girl. Named Champabati, her life changes forever when she is abducted by the morol (village headman). Despite fervent appeals, her husband (Gaya), fails to rescue her. He then leaves the village and marries another girl. Subsequent events lead to a dramatic denouement.

The cast comprises Wahidul Islam, Mominul Haque Dipu, Saida Samsi Ara, Shafiqur Rahman Sagor and Arefa Sultana Lina, among others (Daily Star, June 30, 2006).

Beder Meye is the 28th production of Padatik.

|

Song

5. 1. Songs of Jasim Uddin

Nishite Jaio Phulobane.. Music & Lyrics by Jasim Uddin, Singer: S. D. Burman

Dhire se Janain hindi from Nishite jaio: Music & Lyrics by Jasim Uddin, Singer: S. D. Burman

Bhatiali

Bandhu Rangila Music & Lyrics by Jasim Uddin, Singer: S. D. Burman

O Amar Darodi, Lyric & Music by Jasim Uddin, Singer: Abbasuddin

Nadir Kul Nai Music and Lyric Jasim uddin, Singer: Abdul Alim

O Amar Darodi Music & Lyrics by Jasim Uddin, Singer: Nirmallendu Chaudhuri

Amay Bhasalire..Lyrics and music by Jasim Uddin, Singer: Ferdausi Rahman

Ujan Ganger Naya Music &Lyric by Jasim Uddin, Singer:Nina Hamid

Tora Ke Ke Jabilo Jal ante Music and Lyrics by Jasim Uddin, Singer: Abbasuddin

Gahin Ganger Naya Bhatiali Song, Music and Lyrics by Jasim uddin; Singer: Syed abdul Hadi

Ami baya jaiya kon ghate Bhatiali Song, Music and lyrics by Jasim Uddin

Sharup tui BineMusic and lyrics by Jasim Uddin

Amay Bhasali Re.. Music and Lyrics by Poet Jasim Uddin, Singer: Runa Laila

O Amar Darodi Age Janle Music and lyrics by Poet Jasim Uddin, Singer: Runa Laila

Amay Bhasaili Re In Bengali and Urdu Music and lyrics by Jasim Uddin, Singer: Alamgir

Modern version Amay Bhasaili Re In Bengali and Urdu Music and lyrics by Jasim Uddin, Singer: Alamgir

Bandhu Rangila Rangila Music and Lyrics by Jasim Uddin Prod. Azad Rahman

Amy Baya Jai Kon Ghate Music and lyrics by Jasim Uddin

Boideshi Kanna Famous Bhatiali song Music and lyrics by Jasim Uddin

Love Songs

Kemon Tomar Mata-Pita Kemon Tader HieaMusic and lyrics Jasim Uddin- Afolk dance

Age Janinare dayal Music and Lyrics by Jasim uddin, Singer Neena Hamid

Amar Bandhu binodia Music & Lyrics by Jasim Uddin, Singer: Farida Parveen

Amar Bandhu Binudia Music and Lyrics by Jasim Uddin, Singer: Neena Hamid

Nishite Jaio Phule Bane Music & Lyrics by Jasim Uddin, Singer: Sabina Yesmin

Amay Ato Rate, Music & Lyric by Jasim Uddin, singer: Abbasuddin

Amar Galar HarMusic & Lyrics by Jasim Uddin, Singer: Sabina Yesmin

Oi Shon kadamo Tale Music and Lyric by Jasim Uddin, Singer: Abbasuddin Ahmed

Amar sonar Moina Pakhi Music and Lyrics by Jasim uddin, Singer: Neena hamid

Rangila Rangila - Lyrics and Music by Jasimuddin, Singer: Kiran Chandra Roy

Amar sonar Moina Pakhi Music and Lyrics by Jasim uddin, One of the best song of CloseUp1

Amay Ato Rate Keno Dak Dili Lyric and Music by Jasimuddin- Closeup I

Jaler Ghate Kadomtole- Music &Lyrics: Jasim Uddin, Singer: Abbasuddin

Murshidi Song

Rasul Name Music & Lyrics by Jasim Uddin, Singer: Farida Parveen

Patrioc Songs

Gypsy Songs

Snake Charmer / Babu Selam Lyric and Music Jasim Uddin, dance by Shibli & Nipa

Babu Selam Bare Bar A gypsy song Music and Lyrics by Jasim Uddin

Jasimuddins folksongs delight the audience

F O L K L O R E R E S E A R C H

I N E A S T P A K I S T A N BY ASHRAF SIDDIQUI and A. S. M. ZAHURUL HAQUE

Indiana University, USA

Jasimuddins Asmani released

Asmanider dekhte jadi tomara sabe chao Rahimuddir chhotao barhi Rasulpure jao. If you want to see Asmani, you can go to Rahimuddi’s house in Rasulpur –

wrote Pallikabi Jasimuddin in his famous poem on Asmani, a poverty-ridden rural girl in Rasulpur. Asmani is still alive and now 110 year old. A music company called Sweet Song Products released a music album titled ‘Asmani’ sung by Shamim Afroj Shima at Shaukat Osman Auditorium of Central Public Library on Monday.

The organisers arranged the programme to provide financial help to Asmani, the protagonist of the Pallikabi’s poem of the same title. Managing director of the music company Ridwana Afrin Sumi in her address of welcome said that they want to help Asmani of Jasimuddin’s poem who is still languishing in poverty. ‘We want to help her by giving a part of the sale money from the music album,’ she added.

Former secretary Syed Marghub Murshed was present as chief guest while Mohammad Shamsul Huda, senior vice-president (sales and marketing) of satellite television channel ATN; Mohammad Saidul Haque, executive director of Human Rights Review Society; Selim H Rahman, managing director of Hatil Complex Limited; Nargis Banu, director of Prashika and Imtiaj Mahmud Bhuiyan, chairman of Intellect Trade Link were present as special guests. Rezaul Karim, managing director of Organic Health Care Limited presided over the function. The speakers appreciated the initiatives of the music company in helping Asmani. They said that sufferings of this elderly rural woman were passionately described in the poem by Jasimuddin. The readers of this poem still feel for her but many do not know of her present situation.‘The music company has rediscovered the lady and presented her through the songs in front of the whole nation,’ they added.

Music director Lokman Hakim conducted the programme, followed by a solo performance by the singer.Shima started the soiree singing Asmani, the title song of the album.

Some Remake Songs

Poet Jasim Uddin, Faridpur Region Folk, Bangladesh - 2v

Kobi Jasim Uddin, Faridpur Region Bhatiali (Folk), Bangladesh - 4

Kobi Jasim Uddin, Faridpur Region Folk, Bangladesh - 3

A Tribute to Poet Jasimuddin Bangla Song

Nodir Kul Nai

O Amar Dorodi remix by Sree

PROTIDAN - By Jasim Uddin Recited by Shimul Mustafa

Back to Content

5.2 Old Nazrul Geeti- 78 rpm recorder in 30's

Born into a poor Muslim family, Nazrul received religious education and worked as a muezzin at a local mosque. He learned of poetry, drama, and literature while working with theatrical groups. After serving in the British Indian Army, Nazrul established himself as a journalist in Kolkata (then Calcutta). He assailed the British Raj in India and preached revolution through his poetic works, such as 'Bidrohi' (The Rebel) and 'Bhangar Gaan' (The Song of Destruction), as well as his publication 'Dhumketu' (The Comet). His impassioned activism in the Indian independence movement often led to his imprisonment by British authorities. While in prison, Nazrul wrote the 'Rajbandir Jabanbandi' (Deposition of a Political Prisoner). Exploring the life and conditions of the downtrodden masses of India, Nazrul worked for their emancipation.

Nazrul's writings explore themes such as love, freedom, and revolution; he opposed all bigotry, including religious and gender. Throughout his career, Nazrul wrote short stories, novels, and essays but is best-known for his poems, in which he pioneered new forms such as Bengali ghazals. Nazrul wrote and composed music for his nearly 4,000 songs (including gramophone records) collectively known as Nazrul geeti (Nazrul songs), which are widely popular today. At the age of 43 (in 1942) he began suffering from an unknown disease, losing his voice and memory. Eventually diagnosed as Pick's disease, it caused Nazrul's health to decline steadily and forced him to live in isolation for many years. Invited by the Government of Bangladesh, Nazrul and his family moved to Dhaka in 1972, where he died four years later, in 1976.

In films, we can found Kazi Nazrul Islam as a film director, storyteller, musician, lyricist and actor. Nazrul debuted his film career through the film titled 'Dhruba.' Besides direction, he also acted and directed the music of the film. Then he has had also written story and directed of the films 'Patalpuri,' 'Gora,' 'Bidyapati,' 'Shapurey,' 'Dikshul,' 'Nandini,' 'Chaurangi' and others. Therefore, he also set up film related institution Bengal Tiger Pictures.

However, many films had been made on the basis of the written story of Kazi Nazrul Islam.

ANGUR BALA ....OLD SONG.... AMAR JABAR SHOMAY

Nishi Bhor Holo - Angurbala 78 rpm

Nahay Nahay Prio .. Angur Bala

Kmono Daki--- Angur Bala 78 rpm

Ganguli Mor Ahato..- Angur Bala- Nazrul Geeti.

Bidayya sandha Ahsilo, Angur Bala

Ato Jal Kajol Choke- Angur Bala

Aashile E Bhanga Ghare- Legendor ANGUR BALA

Firoza Begum - Ogo Priyo tobo Gaan

Firoza Begum - Mora Aar Jonome

Angur Bala sings Classic O Sajna

Others

Ghor bhulano surey - Nazrul geeti

chowk gelo- nazrul sangeet by Firoza Begum

Nazrul Geeti - Amar Jabar Shomoy Holo

Brojo Gopi Khaley Hori... sabiha Mahboob

Nazrul geeti

Nazrul was a very dear friend of Jasim Uddin. Nazrul visted Jasim Uddin's parent house at Village Ambikapur, Faridpur twice in 1930s.

Kazi Nazrul Islam, popularly known as rebel poet (vidrohi kobi), was born on the 25th May 1898 at Churulia in the district of Burdwan, West Bengal, India. He was an exceptional talented person in Bangla literature. This patriot, poet, composer writer, political figure or the myriad minded man edited a politico-cultural magazine "Dhumketu". Nazrul was a very dear friend of Jasim Uddin. Nazrul visted Jasim Uddin's parent house at Village Ambikapur, Faridpur twice in 1930s.

Kazi Nazrul Islam, popularly known as rebel poet (vidrohi kobi), was born on the 25th May 1898 at Churulia in the district of Burdwan, West Bengal, India. He was an exceptional talented person in Bangla literature. This patriot, poet, composer writer, political figure or the myriad minded man edited a politico-cultural magazine "Dhumketu".

When still a school student in his teens Nazrul joined the newly recruited Bengali regiment (1916) and sent to Mesopotamia some months before the armistice. The regiment was not given a chance to face battle but all the same Nazrul got his fill of the fighting gusto which later-found expression in poetic effusion and warmth.

His first two significant poems, Pralayollas (Exhilaration at the Final Dissolution) and Vidrohi (Rebellion) appeared early in 1922 and his first book of poem Agnibina (The lute of fire) was out before the year was over. The book was received with an enthusiasm never experienced in India before or since. After he joined the Kollol group and wrote mostly deft and pungent verse and songs galore.

Nazrul Islam wrote a good numbers of valuable poems, songs, novels, dramas. He had a good command on classic Indian song. He could sing, recite and act with considerable proficiency.

Nazrul was an emotional soul, but his emotion was unstable and volatile. Those who came in personal contact with him were moved by his irresistible enthusiasm and sincerity. But his literary output falls far short of his merit, except the early poems in Agnibina. After Agnibina his best known books of poems and songs are Dolonchampa(1923), Biser Bansi (The poisonous flute, 1924), Bhangar Gan (Songs of break-up, 1924), Puber Haoya (The east wind 1925) and Bulbul(1928).

In Nazrul’s works we find that the poet tried to establish women’s long cherished freedom in the conservative society, which gave his creations an added dimension. But unfortunately, because of the poet’s prolonged illness, we failed to get more from this literary genius. This is the high time to conserve the poet’s works, especially the authentic musical notations of his songs.’

Dr Ashraf Siddiqie, a renowned folk exponent said, ‘The Institute seeks to preserve and spread Nazrul’s songs and literature. Up to the present, we have preserved and brought together about 2,000 old gramophone records of Nazrul songs. On the poet’s 29th death anniversary, we bring out an audio CD titled Padmer Dheu Re which is a recollection of the old Nazrul songs in authentic form, by the great artistes like Indu Bala, Angur Bala, Sachin Deb Burman and others of the poet’s own time. We need to publish various publications on Nazrul too.

Abdul Hye Shikdar said, ‘We require Kazi Nazrul Islam’s songs and writings for our development as a nation, and the institute is there to nurture our culture through Nazrul’s works. But there is need for discussions and seminars on the National Poet. His songs and poems need to be made more popular. Awards should be given to those who have done exceptional work on Nazrul (New Age, August 29, 2005)..

Nazrul as Music Director- Film Dhruba

When the National Poet of Bangladesh Kazi Nazrul Islam appeared on the literary stage in Calcutta in the early 1920s with a bang he instantly drew the enthusiastic attention of the appreciative readers of Bengal. As a versatile genius Nazrul traversed almost all the branches of literature, such as, poetry, drama, music, novels etc. Nazrul had another identity; he was closely related to the movies. He was a film director, dialogue writer, music composer and music director. He worked both in Bangla and Hindi films. He worked in more than a dozen films. When the National Poet of Bangladesh Kazi Nazrul Islam appeared on the literary stage in Calcutta in the early 1920s with a bang he instantly drew the enthusiastic attention of the appreciative readers of Bengal. As a versatile genius Nazrul traversed almost all the branches of literature, such as, poetry, drama, music, novels etc. Nazrul had another identity; he was closely related to the movies. He was a film director, dialogue writer, music composer and music director. He worked both in Bangla and Hindi films. He worked in more than a dozen films.

In 1931 Nazrul was offered a prestigious position of music director at Pioneer Films Company. Before Nazrul, no Bangalee Muslim glorified such a respectable post in the world of cinema of Indian subcontinent. Nazrul was related to cinema from 1930 to 1941. During this time he worked in more than 12 movies, such as, Dhruba (1934), Patalpuri (1935), Bidyapati (Bangla version, 1938), Bidyapati (Hindi version, 1938), Nandini (1941) etc.

1933 was a remarkable year for the Bangla cinema. Nazrul's first movie Dhruba began to be prepared. On the first day of 1934 Dhruba was released in Kolkatta. In this cinema Nazrul was the director, songwriter, music composer, singer, and actor. In this movie there were two directors; Nazrul and Saityendranath Dev. It was produced and released by Pioneer Films.

Dhruba included many melodious songs- as many as 18. Among these 18 songs 17 were composed by Nazrul himself, and only one song was composed by Girish Chandra Ghose, a prominent dramatist, who wrote the story of Dhruba. Master Prabodh sang six songs, Angur Bala sang four, Nazrul sang three songs. Parul Bala sang two songs. There were some duets also; Kazi Nazrul Islam and Master Prabodh sang a duet, Angur Bala and Master Prabodh sang another duet song.

It is unknown to the researchers, yet today, as to who was the singer of the song which was written by Girish Chandra Ghose. But it is known to us that Nazrul was the music composer of that song. In Dhruba, Nazrul portrayed the role of Narod.

The Story of Dhruba is just like a fairy tale. In ancient time there was a king named Uttanpad. The name of his wife was Suneeti who was a very pious lady. Everyday she used to worship the idle of Vishnu. So god generously gave them all kinds of wealth. The only lacking of the family was that this couple had no child who would be the next successor to the kingdom. Suneeti, who was extremely devoted to her husband, wanted the king to marry again. Accordingly the king married Suruchee, a beautiful princes. Many days had passed, but Suruchee also failed to give birth to a child. Suruchee was very beautiful but also very cunning. Afterwards, she conspired and the king exiled Suneeti, the first queen, to a forest. One night the king dreamt that his ancestors ordered him to offer meat, from Mrigoya (hunting), to deities. That is why one day the king went a-hunting.

But there rose a terrible rainstorm and the king lost his way. At last he begged shelter standing at the door of a hut. He was given shelter in that hut which was actually the dwelling place of the exiled queen Suneeti. After five years Suneeti came to the touch of her god. In that forest Suneeti gave birth to a child, a boy. The boy was named Dhruba. Day by day Dhruba began to grow as a prince in the hut of the forest. His mother informed him that king Uttanpad was his father.

When Dhruba was only five, once he went to the palace of his father and begged shelter and clothes from his father. The king could recognize him and took him to his arms. The king wanted him to ascend the throne but the second queen Suruchee was in the way. Dhruba came back to his mother crying. At long last the king Uttampad brought the queen Suneeti and their son Dhruba to the place.

In the film Dhruba, Nazrul played the role of Narod. Other central characters were Dhruba - Master Prabodh, king Uttanpad - Joy Narayan, first queen Suneeti - Angur Bala, second queen Suruchee - Sharifa. Nazrul's Dhruba is a milestone in the history of Bengali cinema.

1933 was a remarkable year for the Bangla cinema. Nazrul's first movie Dhruba began to be prepared. On the first day of 1934 Dhruba was released in Kolkatta. In this cinema Nazrul was the director, songwriter, music composer, singer, and actor. In this movie there were two directors; Nazrul and Saityendranath Dev. It was produced and released by Pioneer Films.

Dhruba included many melodious songs- as many as 18. Among these 18 songs 17 were composed by Nazrul himself, and only one song was composed by Girish Chandra Ghose, a prominent dramatist, who wrote the story of Dhruba. Master Prabodh sang six songs, Angur Bala sang four, Nazrul sang three songs. Parul Bala sang two songs. There were some duets also; Kazi Nazrul Islam and Master Prabodh sang a duet, Angur Bala and Master Prabodh sang another duet song.

In the film Dhruba, Nazrul played the role of Narod. Other central characters were Dhruba - Master Prabodh, king Uttanpad - Joy Narayan, first queen Suneeti - Angur Bala, second queen Suruchee - Sharifa. Nazrul's Dhruba is a milestone in the history of Bengali cinema.

Angur Bala

Angurbala had recorded about 300 songs for the Gramophone Company of which 50 were Nazrul songs. "The most interesting experience was when I met Kazi Shaheb for the first time," went on the legendary artiste. Recalling those eventful days, Angur said, "We waited impatiently to meet him. We thought that he would be a bearded man, dressed up in alkhella, with a toopi on his head. However, we were charmed to see a completely different person attired in a gerua panjabi, a yellow silk turban and strings of beads around his neck. A creative genius of his stature never seemed distant.

"Kazi Shaheb would compose tunes focusing on the speciality of the artiste. Sometimes he would just explain the notations and then say in his usual manner 'Angur, it's now up to you to add the sweet angur (grape) flavour of your voice.' That is how I remember Nazrul," reminisced Angurbala.

Amar Jabar Bela - Angur Bala - Old Nazrul Song

Biday Sandhya Aasilo: Angur Bala

Eto Jal O Kajal_Angur Bala_Nazrulgeeti

Nishi Bhor Holo_Angur Bala.

Aamar Jabar Samay Holo Dao Biday_Angurbala Devi

Nahe Nahe Priyo_Angur Bala

Kemone Rakhi Aankhi Bari_Angur Bala

Gaan Guli Mor_Angur Bala

Aashile E Bhanga Ghare_Angur Bala.

Indubala Devi... Thumari Tilang

Angur Bala was basically a stage actress and a singer par excellence. She learnt singing from Amulya Majumdar, Jeet Prasad, Ram Prasad Mitra and Ustad Jahiruddin Khan. At the age of 8, she appeared in stage. In the mean time her first disc was released from HMV under the supervision of Mr. Cooper. She became a singer star within a very short span of time. During this time she was introduced to Kazi Najrul Islam who then joined the gramophone company as a trainer. Under Kazi Najrul Islam’s supervision Angur Bala recorded her first Nazrul Geeti. Parallel to her singing career, Angur Bala continuded her stage acting. Nripen Basu introduced her to Bengal Theatrical Company where she played the lead role in the drama “ Muktar Mukhti” and was highly acclaimed. She acted for a long time in Minerva Theatre. Thereafter she joined the Star Theatre. The important productions of Star theatre she was associated with were “Poysha Putra”, “Chandidas”, "Mamata Shakti”, “Bidrohini” and “Siraj-ud-doula”. She made her film debut in the 1933 film “Jamuna Pulinay” directed by Priyonath Ganguly. Her important films were “Dhruba”, “Abartan”, “India”, “Khona” and “Debjan”. She also acted in several Hindi and Urdu films like “Nasib Ka Chakkar, “Maa ki Mamata”, “Char Darbesh” etc.

She received D.Litt. form Kalyani University. She also received Natak Academy Award. She died in Kolkata on 7th January, 1984.

"Can you explain what a ghazal is?" questioned Arjumand Banu. While I was looking for words, she explained in simple words, "Ghazals originated from Persian poetry based on love. It was Kazi Nazrul Islam who introduced Bangla ghazals that created a massive impact in the music scene. The songs with an exclusive pattern and melody took the music lovers by storm. This was in the year 1926. Nazrul was then hardly 27." There is no end to learning, I thought to myself. That day is firmly etched in my mind.

It was in the same year ('74) that the virtuoso singer Angurbala visited Dhaka. She was the first to record two of Nazrul's ghazals Eto jaal O kajal chokhey and Bhuli kemoney in 1929 for the Gramophone Company that stirred the music aficionados to great heights. Never had they heard such songs with such passionate lyrics and tunes. Surely Nazrul's genius was unparalleled.

From basuuudun Channel Youtube

89 video music etc.- basuuddin Channel - YouTube

Back to Content

5.3 Jasim Uddin: AFC’s First

Collection of Bengali Folksong, Indian Folklife, by JENNIFER CUTTING, Folklife Specialist, and

STEPHEN WINICK, Writer-Editor

In 1958, the American Folklife Center (AFC)

Archive acquired its first recording of Bengali

folksong. Fifty years later, AFC repatriated this

material to Bangladesh, sending a copy to the Folk

Culture Museum at Jasim Uddin House in Faridpur.

The repatriation reflected the American Folklife

Center’s ongoing and evolving commitment to the

preservation and stewardship of intangible cultural

heritage, and to providing communities of origin with

access to their materials.

The field recording in question features Bengali

folklorist and poet Jasim Uddin (1904-1976), known

in Bengali as “Pallikabi,” or “The People’s Poet.”

It contains ten performances of Uddin singing

traditional Bengali folksongs, and providing commentary and English translations for the collectors.

The Jasim Uddin Recording: a Summary

Uddin organized his recording session according the

life-cycle customs of Bangladesh. Hence, his fi rst

selection is what he terms a “birth song,” and this is

followed by a children’s song.

The latter demonstrates

that Uddin was a traditional singer in his everyday life;

upon hearing the recording, Uddin’s son, Dr. Jamal

Anwar, commented: “My father used to sing [this] to

me. I still remember the song….”

The third piece is among the most interesting selections.

It is a rain song, which, Uddin says, unmarried girls

would sing while marching in a procession from house

to house in times of drought. Interestingly, Uddin

described this custom more fully in his poetry:

Into this village came a band of girls

At such a season of dearth;

Singing the song of the marriage of rain,

Th at rain might fall on the earth.

Five girls in a chain, five painted flowers,

But she is without compare,

Who stands in the centre in colour of gold,

The fairest of the fair. 1

Uddin then sings a rhythmic work song, which he states

is for tasks “like pulling a boat for a long distance”;

two war songs for “when the head man of the village is

exciting his comrades to fi ght”; and a narrative song,

“in which the King’s daughter is dressing herself.”

Following the narrative piece, Uddin sings a love song,

and gives a full translation into English, including the

following lines:

“Oh, my beloved friend, had I known

that there would be so much pain…I wouldn’t have

come under the branch of the cottonwood tree, and I

wouldn’t have seen your beautiful face. If you come

to my house, people will scold thee. But if you do not like to, don’t come

to my house, but come to my neighbor’s house and talk loudly so that

I can hear. And, my friend, wherever I go, whatever place I see…

whoever sees me says:

‘This is the girl who has left house and hearth,

and fallen in love with a foreigner.’”

Uddin’s last performance is a mourning song. He

explains that in all of

the previous songs, the words are more prominent

than the tunes. In the mourning songs, he says, the

opposite is true, and the tune may be wordless: “The

village woman in East Bengal…when her daughter

is dead, she cries loudly; she doesn’t care whatever

language may come to her mind; she shouts; only she

is expressing her feelings with some tune.” Uddin

sings the mourning song, and follows it with another

that uses the same tune, prefacing the latter with the

introduction: “There is a little variation in this tune

where the witch doctors are invoking the spirits from

outside to punish them.”

The duration of the recording is fourteen minutes

and two seconds. In this brief span, Jasim Uddin

provides us with Bengali songs on the most important themes of human life: birth and death, childhood

and parenthood, love and confl ict, nature and magic, the fertility of the earth and the ferocity of war.

He organizes the songs to illustrate the life cycle as lived in a Bengali village, revealing himself to be a

knowledgeable tradition-bearer, as well as a thoughtful professor and scholar. Though the recording technique

is crude by today’s standards (e.g. the tape recorder is turned off after almost every song, which interrupts

the continuity and causes the listener to miss parts of Uddin’s explanations), the sound quality on the

recording is very clear, allowing Uddin’s musical and poetic mastery to shine.

Jasim Uddin—Folklorist and Poet

Jasim Uddin was born on January 1, 1903, in

Tambulkhana, a village in the Faridpur district of East

Bengal. As he related in his 1964 autobiography Jibon

Katha, Uddin began reciting and writing poems at

a very early age. “After writing three or four of my

couplets in the notebook I was astonished. There were

fourteen syllables in every line and the last syllable of

every line rhymed with the second line’s last syllable….

Now that I had discovered how to fi nd a rhythm for

my verse, who could hold me back?” By the time

Uddin was a student at Faridpur Rajendra College, he

had already won acclaim as a Bengali poet.

Uddin’s poetry was rooted in the rural Bengali village

life he knew as a child; his language was the language

of the farmers, the fi shermen, the boatmen, and

the weavers of Bengali country villages. Though he

never achieved the international renown of his fellow

Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, Uddin’s work

is well known throughout India and Bangladesh,

and has been translated for school curricula in both

countries.

It has also been translated into European

languages, including English. Tagore himself admired

Uddin, and wrote that “Jasim Uddin has opened a

new school, a new language which is immortal.”

At the time of Uddin’s birth, eastern Bengal was part

of British colonial India. During his childhood, it

was severed from western Bengal and made a separate

province (Eastern Bengal and Assam), which angered

Bengali nationalists. Although the region rejoined the

rest of Bengal in 1912, in 1947 it was again ceded

to become East Pakistan.

In 1971, with help from

neighboring India, this contested land became a

sovereign nation, the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

All of these tumultuous events occurred during

Uddin’s lifetime, and involved the religious division between Muslims and Hindus, as well as the lesser

prestige and political power of Bengali language and

culture relative to the majority cultures of India and

Pakistan

As a Bengali nationalist in this critical period, Uddin

was aff ected by the political and religious divisions of

the era. However, he remained personally opposed to

division within Bengali culture. Although he was a

Muslim, he grew to love and respect the Hindu culture

of his neighbors. In his memoirs, Uddin stressed his

strongly held belief that Bengali culture, especially

literature, belongs to both Hindus and Muslims.

“Th ose who would separate the two [cultures] and

write literature will not last many days, I am sure,” he

wrote.

Uddin was himself aff ected by this issue. In the 1920s

one of his poems was included in the matriculation

exam at the University of Calcutta, which caused some

controversy among the Hindu majority; his inclusion

was defended by his mentor and friend, Professor

Dinesh Chandra Sen. Uddin also treated the theme

of religious division in his own writings, especially the

long narrative poem “Gipsy Wharf ”, which depicts a

romance between a Muslim boy and a Hindu girl. In

attempting to depict both communities fairly, Uddin

created a work that spoke to most Bengali people, and

that has survived the test of time.

Uddin was also an important folklorist. From 1931 to

1937, as a Ramtanu Lahiri Scholar at the University of

Calcutta, he collected several thousand rural Bengali

folksongs under the guidance of Professor Sen. In

1938 he left Calcutta to teach at the University of

Dhaka. In 1944 he joined the government of East

Pakistan in the Department of Information and

Broadcasting. He retired as the deputy director of that

agency in 1962. During the course of Uddin’s career,

he collected over ten thousand folksongs, making him

one of the most successful folklore collectors of his

time. In addition, he wrote important articles and

books on the interpretation of Bengali folksongs,

folktales and other genres. Th is scholarly activity

gives the AFC recording even greater interest for

international scholars in ethnographic disciplines such

as folklore, ethnology, and ethnomusicology.

The Jasim Uddin Recording: An Archival

History

Staff at the American Folklife Center did not become

aware of the importance of the Jasim Uddin recording

until September, 2008, when Dr. Jamal Anwar, Uddin’s son, contacted AFC to request a copy for

the Folk Culture Museum at Jasim Uddin House

in Faridpur, Bangladesh. AFC staff made the copy,

thus repatriating this small sample of Bengali cultural

heritage.

The original recording was made on July 24, 1957, by

Sidney Robertson Cowell and her husband, composer

Henry Cowell, who were conducting fi eld research in

Asia. The recording came to the AFC Archive as part

of the Sidney Robertson Cowell Duplication Project,

and its history is recounted in a memo written on

May 14, 1958, by Rae Korson, then the Head of the

Library’s Archive of Folk Song, to Harold Spivacke,

then Chief of the Library’s Music Division:

“Mrs. Cowell recorded twelve double-track tapes of

various sizes and has now very generously off ered to

permit the Library of Congress to duplicate them

for the collections in the Archive of Folk Song.

The Cowells have expressly avoided depositing the

recordings elsewhere in the hope that, by being in

the Library of Congress, these important sound

documents would be available to the greatest number

of scholars. The countries represented in this widely

varied collection are Iran, India, Pakistan, Burma,

Th ailand, and Malaysia.”

During the 1950s, southern and southeastern Asia

were represented in the Archive only by thirty-nine

short commercial discs from India, a single reel

of Pakistani music for the sitar, and two reels of

songs and instrumental music made in the Library’s

recording studio by a visiting Th ai musician. For

that reason, Korson explained, “we feel that for this

area in particular, we must take advantage of every

opportunity which presents itself.” Fortunately,

Spivacke agreed, and the duplication project went

forward; as a result, the recording has not only been

preserved at the Library, but repatriated to Bangladesh,

where it can be heard in the museum at Faridpur.

Since the 1950s, AFC has greatly expanded its

holdings of South Asian materials. The full list of

AFC’s South Asia collections can be consulted in our

online fi nding aid, South Asia Collections in the Archive

of Folk Culture, at http://www.loc.gov/folklife/guides/

SouthAsian.html

Endnotes

1 Uddin, Jasim (Jasimuddin). 1939. The Field of the

Embroidered Quilt: A Tale of Two Indian Villages (translated

from Bengali to English by E.M. Milford). Calcutta:

Oxford University Press, Indian Branch.

|