|

1. Introduction

Purbabanga-Gitika a collection of folk ballads of East Bengal. These ballads, composed orally and performed among the rural communities, are important resources of bangla literature. The ballads were collected from Mymensingh, Netrakona, Chittagong, Noakhali, Faridpur, Sylhet and Tripura. The main collectors of these ballads include chandra kumar de, dinesh chandra sen, ashutosh chaudhuri, jasimuddin, Nagendrachandra Dey, Rajanikanta Bhadra, Bihari Lal Roy and Bijay Narayan Acharya.

Purbabanga-Gitika a collection of folk ballads of East Bengal. These ballads, composed orally and performed among the rural communities, are important resources of bangla literature. Purbabanga-Gitika a collection of folk ballads of East Bengal. These ballads, composed orally and performed among the rural communities, are important resources of bangla literature. The ballads were collected from Mymensingh, Netrakona, Chittagong, Noakhali, Faridpur, Sylhet and Tripura. The main collectors of these ballads include chandra kumar de, dinesh chandra sen, ashutosh chaudhuri, jasimuddin, Nagendrachandra Dey, Rajanikanta Bhadra, Bihari Lal Roy and Bijay Narayan Acharya.

Purbabanga-Gitika a collection of folk ballads of East Bengal. These ballads, composed orally and performed among the rural communities, are important resources of bangla literature.

The ballads were collected from Mymensingh, Netrakona, Chittagong, Noakhali, Faridpur, Sylhet and Tripura. The main collectors of these ballads include Chandra Kumar De, Dinesh Chandra Sen, Ashutosh Chaudhuri, Jasimuddin, Nagendrachandra Dey, Rajanikanta Bhadra, Bihari Lal Roy and Bijay Narayan Acharya.

Over 50 ballads are included in the collection, among them Dhopar Pat, Maisal Bandhu, Kanchan Mala, Kamala Ranir Gan, Madankumar O Madhumala, Nejam Dakater Pala, Dewan Isha Khan, Manjur Ma, Kaphenchora, Bheluya, Hatikheda, Aynabibi, Kamal Sadagar, Chawdhurir Ladai, Gopini-Kirtan, Suja-Tanayar Bilap, Baratirther Gan, Nurunnechha O Kabarer Katha and Paribanur Hanhala.

Most of these ballads were composed in the 14th century, with some being composed in the 16th and 17th centuries.

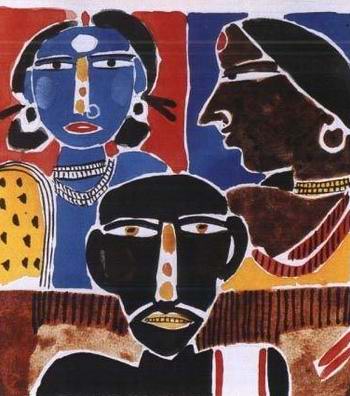

The composers of these ballads were uneducated or half-educated farmers or boatmen. Their themes included love affairs, rivalry between different zamindars, and significant events effecting the life of the people. These were composed in the form of rhymes or panchali. Later, groups of singers used to set them to music and perform them in villages.

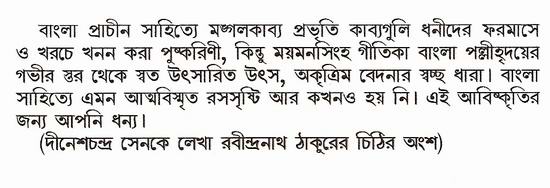

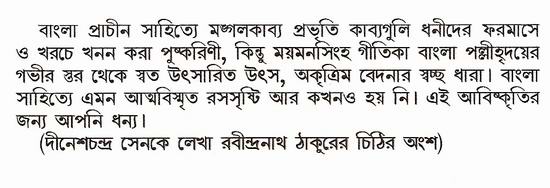

Chandrakumar De started publishing some of these folk ballads from 1913. These attracted the attention of Dineshchandra Sen who met Chandrakumar. With his help Dineshchandra collected quite a few of these ballads from the villagers. Calcutta University provided financial support for the collection which was published as Purbabanga-Gitika in 1926. Dineshchandra translated these ballads into English. The collection, titled Eastern Bengal Ballads, was published in four volumes by Calcutta University in 1923.

Volume 1: Eastern Bengal Ballads : Mymensigh (1923), contains ten ballads: Volume 1: Eastern Bengal Ballads : Mymensigh (1923), contains ten ballads:

Mahua (1-30pp), Malua (31-80), Chandravati (81-102), Kamala (103-138), Dewan Bhavna (139-162), Kenaram the Robber Chief (163-180), Rupavati (181-204), Knaka and lila (205-242), Kajal Rekha (243-282), and Dewan Madina (283-312.

Back to Content

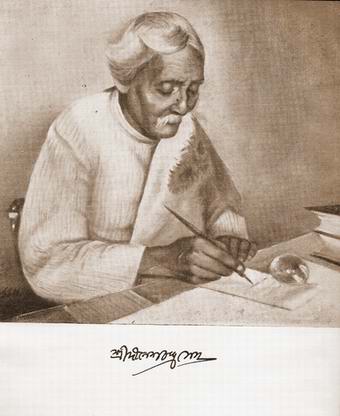

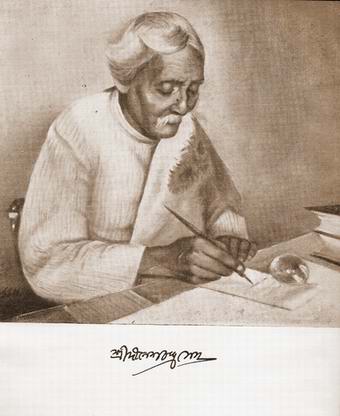

2 Rai Bahadur Dinesh Chandra Sen (1866-1939)

|

Dr. Dinesh Chandra Sen was pioneer in recovering the rich treasure of folk songs, ballads and literature of Bengal and builder of the Department of Bengali Language and Literature of the university of calcutta.

Here it is useful to pay some attention to the works of Dinesh Chandra Sen, the pioneering historian and a lifelong devotee of Bengali literature.4 Once hailed as the foremost historian of Bengali literature, he was lampooned by a younger generation of intellectuals in the 1930s who faulted his sense of both politics and history. Here it is useful to pay some attention to the works of Dinesh Chandra Sen, the pioneering historian and a lifelong devotee of Bengali literature.4 Once hailed as the foremost historian of Bengali literature, he was lampooned by a younger generation of intellectuals in the 1930s who faulted his sense of both politics and history.

Born in a village in the district of Dhaka in 1866, Dinesh Chandra Sen (or Dinesh Sen for short) graduated from the University of Calcutta with honors in English literature in 1889 and was appointed the headmaster of Comilla Victoria School in 1891 in Comilla in Bangladesh.

While working there, he started scouring parts of the countryside in Eastern Bengal in search of old Bengali manuscripts.

The research and publications resulting from his efforts led to his connections with Ashutosh Mukherjee, the famed educator of Bengal and twice the vice chancellor of the University of Calcutta (1906–1914 and 1921–23).

In 1909, Mukherjee appointed Sen to a readership and subsequently to a research fellowship in Bengali at the university.

Sen was eventually chosen to head up the postgraduate department of Bengali at the University of Calcutta when that department— perhaps the first such department devoted to postgraduate teaching of a modern Indian language—was founded in 1919.

Sen served in this position until 1932. He died in Calcutta in 1939. Sen produced two very large books on the history of Bengali literature:

Bangabhasha o shahitya (Bengali Language and Literature) in Bengali, first published in 1896, and

History of Bengali Language and Literature (in English), based on a series of lectures delivered at the University of Calcutta and published in 1911.

He also produced many other books including an autobiography. All his life, Sen remained a devoted, tireless researcher of Bengali language and literature.

Dinesh Chandra Sen wrote and edited about 55 books in Bangla and twelve books in English in addition to a large number of research articles published in various learned journals. Apart from Banga Bhasa O Sahitya, his works include Ramayani Katha (Tales of Ramayana), 1904; Behula (a folk tale), 1907; Vaidik Bharat (Vedic India: based on stories from the Vedas), 1922; Pauraniki (Tales from the Puranas), 1934; and Brhat Banga (Greater Bengal: a social history) in two volumes, 1935. His major English works include History of Bengali Language and Literature (1911), Sati (1916), The Vaishnava Literature of Medieval Bengal (1917), The Folk-Literature of Bengal (1920), Bengali Prose Style, Chaitanya and His Age (1922), Eastern Bengal Ballads of Mymensingh in four volumes (1923-1932) and Glimpses of Bengal Life (1925).

THE HISTORY OF ANCIENT BENGAL

The territory inhabited by Bengal-speaking people goes beyond the boundary of Bengal, which stretches from the Himalayas in the north to the Bay of Bengal in the south, from Brahmaputra, Kangsa, and Surma in the east to Nagar, Barakar and Suvarnerekha in the west. The majority of people in the western areas are Hindus, while in the east Muslims predominate. Although there are strong feeling towards Bengali and Bangladeshi nationalism, broadly speaking the term Bengal designates the Bengali-speaking area.

In most characteristic feature of the Bengali landscape is its vast river system which characterizes the Bengali people and their literature. Among the main rivers the Ganges and the Padma are the two most important and these are referred to in many literary compositions, including the carya poems. Bengal was famous in ancient times for river and sea crafts. The arts of navigation, boat building and maritime warfare developed because of the many rivers and the long seacoast. Bengal carried on a large sea trade mostly through the ancient seaport of Tamralipta. River and sea voyages are often characterized in Bengali folklore and literature, particularly in the Manasa and Chandi poems composed later than the caryas.

Being situated in the extreme east of India, Bengal served as the connecting land link between the sub-continent, Burma, South China and the Malay Peninsula and Indo-China. Bengal not only acted as intermediary in trade and commerce but also played an important role in the cultural association between the diverse civilizations of South East and Eastern Asia. An inscription in the Malay Peninsula of the fourth or fifth century A.D. records the gift of a great captain Buddhagupta, who was probably Bengali. It is also said that it was a Bengali prince, Vijaya, the Pala period. There is an affinity between the scripts used on Javanese sculptures and the proto-Bengali alphabets. The influence of ancient Bengal was of Tibet and China.

Diverse civilization and cultures met in the Bengal delta. Various races entered India during pre-historic times through the North West of the Indian sub-continent and lived there until they were driven further east. Bengal continually attracted people from outside.

There are many accounts and references which point out that the ancient people of Bengal were different in race, culture and language from the Aryans who compiled the Vedic literature. The original inhabitants of Bengal were non-Aryan. Many linguists and anthropologists believe that the early tribes of Bengal were Dravidian, but belonged to a separate family1

It used to be accepted that the Brahmins and other high castes of Bengal were descended from the Aryan invaders who imposed their culture upon the primitive barbarian tribes of Bengal. Although we know very little of pre-Aryan Bengali civilization, it is now generally held that the foundations of the agriculture -based village life, which is also believed to be one of the foundations of Indian civilization, were laid by the Nishadas or Austric -speaking peoples of Bengal. According to Dr. S. K.Chatterji, the Austric tribes of India belonged to more then one group of the Austro- Asiatic section, i.e. to the kol, the khasi and the mon -khmer group.

It may be presumed that Bengal had developed a culture of its own which was non-Vedic and non-Aryan. It is true that the Aryan culture, and the Vedic, Buddhist and Jaina religions influenced Bengal. The primitive culture became absorbed but it also influenced its adopted religion

The rise of the anti-Brahmin and the anti-sacrificial ideas of the Buddhists and the Jains among the eastern people or Bengalis shows that other strong traditions were established before the Brahmins came and that Vedic ideas brought by the Brahmin did not inspire the masses. According to Dr. Dinesh Chandra Sen, the country was for centuries in open revolt against Hindu orthodoxy. Buddhist and Jain influences were so great that the Hindu code of Manu prohibited all contact of the Hindus with this land; hence Brahminism could not thrive there for many centuries. With the revival of Hinduism the Sanskrit pundits did not accept works in Bengal were carried away to Nepal and Burma as Buddhism was gradually suppressed in India by the Brahmins. Sanskrit scholars from outside Bengal who brought about a Hindu revival in Bengal abhorred the simple Bengali language.

Sen's literary output

Along with the proliferation of Sen's literary output, his worldly status had also gone up. In 1909, he was appointed reader in the Department of Bengali Language and Literature of Calcutta University and was entrusted with the responsibility of building and developing the new faculty. He was made Ramtanu Lahiri Professor in 1913. Calcutta University conferred on him the degree of Doctor of Literature in recognition of his work in 1921 and Jagattarini Gold Medal in 1931.

Sen, today, is truly a man of the past. His almost exclusive identification of Bengali literature with the Hindu heritage, his idealization of many patriarchal and Brahmanical precepts, and his search for a pure Bengali essence bereft of all foreign influence will today arouse the legitimate ire of contemporary critics. It is not my purpose to discuss Sen as a person. But, for the sake of the record, it should be noted that, like many other intellectuals of his time, Sen was a complex and contradictory human being. This ardently and (by his own admission) provincial Bengali man loved many English poets and kept a day's fast to express his grief on hearing about the death of Tennyson. 8. For all his commitment to his own Hindu-Bengali identity, he remained a foremost patron of the Muslim-Bengali poet Jasim Uddin. 9. The inclusion of a poem by Jasim Uddin in the selection of texts for the matriculation examination in Bengali in 1929, when Hindu-Muslim relations were heading for a new low in Bengal, was directly due to Sen's intervention at the appropriate levels. 10. And his patriarchal sense of the extended family did not stop him from encouraging his daughters-in-law to pursue higher studies.

Sen was a complex and contradictory human being. This ardently and (by his own admission) provincial Bengali man loved many English poets and kept a day's fast to express his grief on hearing about the death of Tennyson. For all his commitment to his own Hindu-Bengali identity, he remained a foremost patron of the Muslim-Bengali poet Jasimuddin. The inclusion of a poem by Jasimuddin in the selection of texts for the matriculation examination in Bengali in 1929, when Hindu-Muslim relations were heading for a new low in Bengal, was directly due to Sen's intervention at the appropriate levels. 10. And his patriarchal sense of the extended family did not stop him from encouraging his daughters-in-law to pursue higher studies.

( Prof. Dipesh Chakrabarty, Kimpton Distinguished Service Professor of History and South Asian Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago. His latest book is Habitations of Modernity: Essays in the Wake of Subaltern Studies (Chicago, 2002).

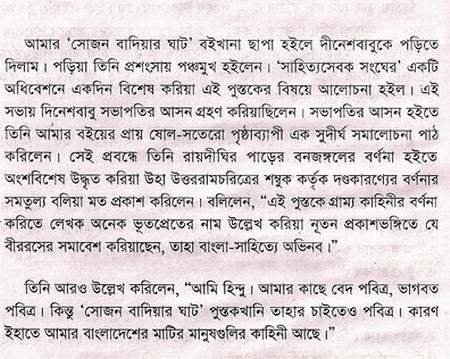

Sen’s relationship to Jasim Uddin*

By the time he was a student at Faridpur Rajendra College his poetry had already won him some fame. Kobor (Graves) was prescribed as the text for the Matriculation Examination at Calcutta University when Jasim Uddin was still a student in the 1. A. Class (Rajenra College, under Calcutta University)

I was surprised when in 1929 I read Jasim Uddin's poem "Kabar" in Calcutta University’s selection of Bengali texts for the Matriculation examination. A poem by a Muslim writer in the Matriculation selections! And that too under the auspices of the University of Calcutta? . . . A teacher of mine told me a story about this. There was forceful opposition in [the University's] Syndicate to the inclusion of by a student. But Dr Dinesh Sen was the number one advocate for Jasim Uddin. . . . Apparently, he countered the opposition by saying, "All right, please be patient and just listen to me recite the poem." He had a passionate voice and could recite poetry well. He read the poem with such wonderful effect that the eyes of many members of the Syndicate were glistening with tears.

-

Wahidul Alam, "Kabi Jasimuddin," Alakta, 5 no. 2 [1983]; quoted in Titash Chaudhuri, Jasimuddin: Kabita, gadya o smriti

The poet asserts he gathered material for his plot from actual happenings in his own Faridpur district. 'In our Faridpur district there live many poor farmers, Moslem and Namasudra (Hindus).

"But from my boyhood to the present day for the love aud affection which I received from the sannyasi there remains a love and respect in my heart which has not in the least bit been destroyed.For the friendship of the sannyasi and the insight he gave " him into Hindu culture,J asim Uddin is still grateful. It seems to me his broadmineledness and sympathy for Hindu as well as Moslem tradition are among his best qualities as a writer. Gipsy Wharf is almost a plea for bettel' Hindu-Moslem relations. Certainly he believes that the bonds which unite Bengali people are very strong, and the culture they have , made is both Moslem and Hindu.

Sen’s relationship to Jasimuddin is the subject of the latter’s reminiscence in Smaraner sharani bahi (Calcutta, 1976). Jasimuddin writes:

Here was a man who took me from one station in life to another. My student life perhaps would have ended with the I.A. [Intermediate of Arts] degree if I had not met him. Perhaps I would have spent my life as an ill-paid teacher in some village school. I think of this not just only once. I think this every day and every night and repeatedly offer my pronam [obeisance] to this great man. [P. 71]

|

|

It was at this time that Dinesh Chandra turned into an enthusiastic collector of the surviving fragments of Bengal's past. He moved from village to village collecting old Bangla manuscripts, folk songs, folk myths and legends and folk language and ballads, realising that, unless collected, these treasures would soon perish and disappear forever. Based on his empirical research, in 1986, he published his first monumental work entitled Banga Bhasa O Sahitya (Bangla Language and Literature), the first comprehensive and scientific study by any Bengali scholar so far. This work fetched him instant recognition as a scholar of rare ability.

(* Poet Nazrul Islam taught Jasim to write his name like Jasim Uddin (ud-din), Jasim Uddin followed Nazrul's advise)

Back to Content

3. Baromashi

Sen in the first volume presented baromashi songs or the songs of twelve months. In these songs each of the twelve months of the year presents, as it were, a bioscopic scene of the landscape of Bengal.

The earliest poetic tradition of the country was that bengali poem could not be complete withoutbaromasi or an account of the twelve month. We have found baromasi even from the days of aphorisms of Dak and Khana in the ninth century (Dinesh Chandra Sen).

Kamalar Baromasi

Kamalar Baromasi collected by Poet Jasim Uddin in Faridpur, Bangladesh about thirty years ago. The song represents songs of separation with the happy end (Dr. Dusan Zbavitel, The Development of baromasi, Folklore of Bangladesh, Bangla Academy,1987):

In this month of Agrahayan, all four ridges

are solid.

Paddy of different colours ripened in my fields

I shall prepare rice from paddy of various colours

The merchant of my heart is not at home, to whom

shall I give it?

In this month of Paush, there is the darkness of

Paush.

nights being dark, thieves go from one house to

another.

let the thieves come, I am not afraid of them.

Father and brother are the ring round my body and

my father-in-law, the merchent.

In this month of Magh, coldness is like poison

Kamal lays the bed with cotton mat in the inner

house.

Laying in the bed with the cotton mat she looks at the

room-

Why does the room of the poor woman look empty?

The cotten robe, the cotton mat, the cotton pillow on

her breast.

You sinful cotton pillow, there is no answer in thy

mouth!

|

|

In this month of Phalgun, householders sow the seed. In this month of Phalgun, householders sow the seed.

The girl a cup full of poison.

I shall eat poison, i shall eat venom, I shall die,

But shall never (again) marry a boatman.

The boatman is the great scoundrel, a servent of the

business.

Having married me, he went away and never cared

about me.

In this month of chaitra, the wind chaitali is at its

height.

The wife whose merchant at home is very proud

What a wife is she whose merchant is not at home?

I am unhappy wife, I am dying in pains.

In this month of Baisakh, there is spinach and jute

leaves.

All people eat spinach, the limbs of the wife are

bitter.

She cooked and prepared spinach and poured it on a

plate.

My dear merchant is not at home, whom shall I give it?

In this month of Jaysto hot is the sun

Hundred of mangoes are ripe and huge jack-fruits

I would eat mangoes, I would eat jack-fruits,

milk of five cows.

If my dear merchent were at home, we would play

together.

In this month of Ashar, there is new water in Ganges,

The milkwoman shouts :"Take curds! Take Curd!

Whose curds who will take, who would like to eat it?

The merchant is not at home, my days pass in fasting.

In this month of Sraban, householder cut the paddy

the kora-bird calls, sitting on the rice stalk.

Dakcalls, damphala calls, bora calls, sitting there,

the call of the cruelkokil made my ribs split.

In this month of Bhadra tal-fruits (palm) are ripe in the trees,

The young girl went out with a plate in her hands.

She took her plate, she took a box, she took a quilt on

her head

Wandering around she went where her dear merchant

had gone.

In this month of Ashwin there is the new

Durga festival.

Let the brahmin wives offer flowers (to the goddess)

Let them offer offer flowers, let them take the offerings

home.

If my dear mervhant comes home, I shall offer to

him.

In this month of Kartik , betel-buds are on the

trees.

The dear merchant comes home, with an umbrella

over his shoulder.

Back to Content

3.1 Months of the Bengali/Indian Civil Calendar

Days Correlation of Indian/Gregorian

|

|

1. Chaitra 30 |

March 22 |

| 2. Baisakh-31 |

April 21 |

| 3. Jyaistho-31 |

May 22 |

| 4. Asahar -31 |

June 22 |

| 5. Sravan |

July 23 |

| 6. Bhadra--31- |

August 23 |

| 7. Ashwin-30 |

September 23 |

| 8. Kartik--30 |

October 23 |

| 9. Agrahayan-30 |

November 22 |

|

| 10. Paus--30- |

December 22 |

| 11. Magh--30- |

January 21 |

| 12. Falgun--30 |

February 20 |

* In a leap year, Caitra has 31 days and Caitra 1 coincides with March 21.

The history of calendars in India is a remarkably complex subject owing to the continuity of Indian civilization and to the diversity of cultural influences. Early allusions to a lunisolar calendar with intercalated months are found in the hymns from the Rig Veda, dating from the second millennium B.C.E. Literature from 1300 B.C.E. to C.E. 300, provides information of a more specific nature.

Before the introduction of the Bangla Calendar, agricultural and land taxes were collected according to the Islamic Hijri calendar. However, as the Hijri Calendar is a lunar calendar, the agricultural year did not always coincide with the fiscal year. Therefore, farmers were hard-pressed to pay taxes out of season. In order to streamline tax collection, the Mughal Emperor Akbar ordered a reform of the calendar. Accordingly, Amir Fatehullah Shirazi, a renowned scholar of the time and the royal astronomer, formulated a new calendar based on the lunar Hijri and solar Hindu calendars. The resulting Bangla calendar was introduced following the harvesting season when the peasantry would be in a relatively sound financial position. In keeping with the harvesting season, this new calendar initially came to be known as the Harvest Calendar, or Fôsholi Shôn.

The new "Fôsholi Shôn" was introduced on 10 March / 11 March 1584, but was dated from Akbar's accession to the throne in 1556. The new year subsequently became known as Bônggabdo or Bangla Shôn ("Bengali year").

The zero year of the Bangla calendar coincides with the zero of the Islamic Hijri calendar since it was introduced by a Muslim Mongol conqueror of India, Emperor Akbar, descendant of Babar, Tamerlane and Chenghis Khan. Today the two calendars have diverged and have two different years.

The Bangla calendar was made a solar calendar to better coincide with harvest times and facilitate better collection of taxes. This caused the difference between the Hijri year and the Bangla year. The Hijri lunar calendar is 11/12 days shorter than the solar year and so has raced ahead. The Hijri year today (January, 2003) is 1422 while the Bangla year is 1409.

The Bengali Calendar in use today was created by Emperor Akbar (or rather someone under him) on March 10 or 11th 1584/5 AD. It amalgamated the old Indian calendar and the Islamic Hijri (Arabic) calendar and was originally called Tarikh-e-Elahi... now Bangla Shaal (possibly the name of the old calendar). That was not, however, year zero. Since Akbar had ascended the throne in the year 1556 AD and his new calendar was backdated to that year which was the year 963 in the lunar Hijri era (Islamic calendar). So the new Bangla calendar began at 963 with zero coinciding with the zero of the Hijri calendar.

The months, Boishakh, Joishtho, Asharh, Srabon, Bhadra, Ashwin, Kartik, Agrahayon, Poush, Magh, Falgun, Chaitra are used. Boishakh, Joishtho, etc. are Bengali names as opposed to non-Indian names used by Akbar. The Bangla names from the older calendar prevailed.

Originally in the region, the first of Chaitra was the beginning of the new year but a new date was selected by Akbar and his administration. It was a date selected from both the Arabic and the Bengali calendars. In 963 AH (Hijri) the first arabic month, Muhurram, had coincided with Baishakh (Boishakh). So the first of Boishakh (Pahela Boishakh) was selected as the first day of the year replacing Chaitra first. Even though the names of the original

Translated by: ZBAVITEL Dušan - ceský indolog

|

References:

D.-k.: L'orientalisme en Tchécoslovaquie (též angl., nem. a rus.), Praha 1959;

(s E. Heroldem a K. Zvelebilem), Indie zblízka, Praha 1960 (nem. 1961);

Rabíndranáth Thákur. Vývoj básníka, Praha 1961;

Ocenka Tagorom Dviženija svadeši posle 1905, Moskva 1961;

Bengali Folk-Ballads and the Problem of their Authenticity, Calcutta 1963;

(s J. Markem), Dvakrát Pákistán, Praha 1964 (nem. 1966, rus. 1966);

(s kol.), Bozi, bráhmani, lidé. Ctyri tisíciletí hinduismu, Praha 1964 (rus. 1969);

The Rise of Modern Literature in Asia, with Special Reference to Bengal, Calcutta 1966;

Lehrbuch des Bengalischen, Heidelberg 1970, 3. vyd. 1997;

Non-Finite Verbal Forms in Bengali, Praha 1970; (s kol.), Moudrost a umení starých Indu, Praha 1971;

Bangladéš. Stát, který se musel zrodit, Praha 1973;

Bengali Literature, Wiesbaden 1976;

(s kol.), Setkání a promeny, Praha 1976 (pol., 1983);

Jedno horké indické léto, Praha 1982 (rus. 1986);

Staroveká Indie, Praha 1985; (s kol.), Bohové s lotosovýma ocima, Praha 1987 (2. vyd., 1997);

Divadlo južnej Azie, Bratislava 1987;

Sanskrt, Brno 1987; (s D. Kalvodovou), Pod praporem krále nebes. Divadlo v Indii, Praha 1988;

Hinduismus a jeho cesty k dokonalosti, DharmaGaia, Praha 1993;

(s J. Vackem), Pruvodce dejinami staroindické literatury, Trebíc 1996;

Otazníky staroveké Indie, Nakladatelství Lidové noviny, Praha 1997.

Note: I am very grateful to the Bengali Academy Dacca, for having been given an oppertunity to consult their collection, and to my friend, the Poet Jasim uddin, dacca, who placed to my disposal some baromasiscollected by him. - Dr. Dusan Zbavitel,Oriental Institut Praha, czechoslavakia.

Poet Jasim Uddin collected more than 10 thousands folk songs. During his life time Bangla Academy refused to publish the collection with interpretation and for this ground he refused to accept the Bangla Academy literary Award in 1975. It took seven years to publish Jari Gan by the Bangla Academy. It is pity that academy did not show any intrest. It is a great national loss that the academy did not take any action to preserve our national heritage.

Back to Content

4. Ballet - Pala

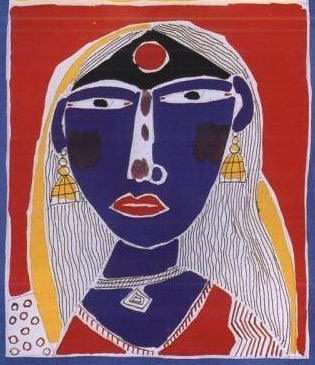

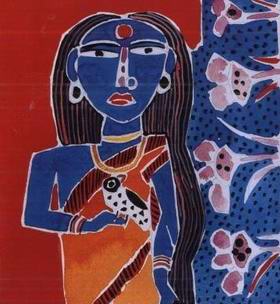

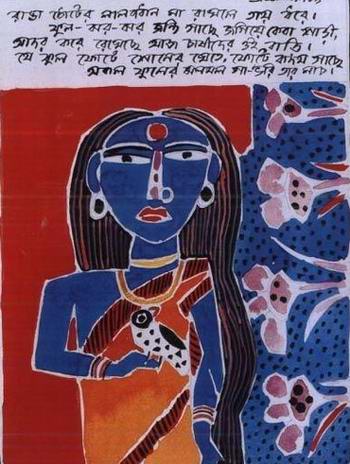

4.1 Chandrabati is the first woman Bangali poet

Kishoreganj a northern district of Dhaka, is enriched with archaeological heritage. People are very proud of and talk a lot about their rich cultural heritage. Poems of Chandrabati are a hot topic. They talk very highly about Jangalbari, and about boating on the haor. We decided to visit Chandrabati's house Jangalbari. Kishoreganj a northern district of Dhaka, is enriched with archaeological heritage. People are very proud of and talk a lot about their rich cultural heritage. Poems of Chandrabati are a hot topic. They talk very highly about Jangalbari, and about boating on the haor. We decided to visit Chandrabati's house Jangalbari.

Chandrabati is the first woman Bangali poet whose tragic life has touched many hearts. She was born in the 16th century in a Brahmun family. Her parents were Dija Bangshidash and Sholochona. Chandrabati was guided by her father, another historical personality well-known for his gathas or odes such as Mahua and Komola.

Beautiful Chandrabati was in love with a Brahmin boy called Joychandra. The two were to get married when suddenly Joychandra jilted her for another woman. Chandrabati, heart broken decided to remain celibate all her life. Seeing her in such grief Chandrabati's father advised her to occupy herself reciting the Ramayana and in praying. Her loving father Dija also made a separate Shiva temple for her to pray next to his manasha temple.

Chandrabati devoted herself to reciting and, writing odes and in praying. Some of her well-known odes are: Malua, Dossho Kenaram and Ramayana Katha (incomplete). Beautiful Chandrabati was in love with a Brahmin boy called Joychandra. The two were to get married when suddenly Joychandra jilted her for another woman. Chandrabati, heart broken decided to remain celibate all her life. Seeing her in such grief Chandrabati's father advised her to occupy herself reciting the Ramayana and in praying. Her loving father Dija also made a separate Shiva temple for her to pray next to his manasha temple.

Chandrabati devoted herself to reciting and, writing odes and in praying. Some of her well-known odes are: Malua, Dossho Kenaram and Ramayana Katha (incomplete).

Joychandra soon realised that he still loved Chandrabati and tried to win her back. As the legend goes, one day while Chandrabati was praying in her closed-door temple, Joychandra came to her begging to come back. As she was not opening the door, Joychandra wrote a love letter on the temple wall with red malati flowers. When Chandrabati opened the door, it was too late-- Joychandra had committed suicide by drowning himself in the river next to the temple. Chandrabati could not bear this sight and she too took her own life.

The government has declared these two temples as national heritage sites, but conditions of these temples are worsening according to Tulshi Das. He says that there is a school in Chandrabati's name but the historical house, which was built by Dija, is totally damaged.

Tulshi Das, descendant of Chandrabati, Das hopes that the government and individuals will come forward to repair this historical place and build a heritage museum in memory of Chandrabati.

Ancient wisdom, as handed down in the form of legends and folklore, offers the best escape route from the sufferings of a world full of unhappiness, discord and hatred. Being staged as part of Ganakrishti's annual theatre festival, Chandrabati is a simple tale of love and longing that inspires and re-awakens in us faith in the fundamental virtues and values of life. Based on a popular story from Maimansingha Geetika, a collection of centuries-old Bangladeshi pala (ballads), the play narrates the life of its eponymous protagonist. Friends since childhood, Chandrabati and Jayananda fall in love and decide to get married. However, impressed by the beauty of another woman, Asmani, Jayananda sends letters to her, expressing his feelings of admiration. Despite being aware of Jayananda?s pledge to Chandrabati, Asmani informs her father about Jayananda, and he is forced to marry Asmani. Shocked and betrayed, Chandrabati becomes a recluse and spends her days in worship, finally refusing a repentant Jayananda when he returns. Direction: Manish Mitra.

Event: Play in Bengali, Chandrabati, produced by Kasba Arghya (The Telegraph, July 23, 2005) Ancient wisdom, as handed down in the form of legends and folklore, offers the best escape route from the sufferings of a world full of unhappiness, discord and hatred. Being staged as part of Ganakrishti's annual theatre festival, Chandrabati is a simple tale of love and longing that inspires and re-awakens in us faith in the fundamental virtues and values of life. Based on a popular story from Maimansingha Geetika, a collection of centuries-old Bangladeshi pala (ballads), the play narrates the life of its eponymous protagonist. Friends since childhood, Chandrabati and Jayananda fall in love and decide to get married. However, impressed by the beauty of another woman, Asmani, Jayananda sends letters to her, expressing his feelings of admiration. Despite being aware of Jayananda?s pledge to Chandrabati, Asmani informs her father about Jayananda, and he is forced to marry Asmani. Shocked and betrayed, Chandrabati becomes a recluse and spends her days in worship, finally refusing a repentant Jayananda when he returns. Direction: Manish Mitra.

Event: Play in Bengali, Chandrabati, produced by Kasba Arghya (The Telegraph, July 23, 2005)

Back to Content

4.2 Chandraboti

Chandraboti was a sixteenth-century poet from Mymensingh who has been immortalized as the heroine of Joy-Chandraboti, a Mymensingh Geetika. The ballad tells the story of Chandraboti’s love for Joychandra. The two were to get married when Joychandra rejected her for a Muslim girl. Joychandra tried to return to Chandraboti, but Chandraboti rejected her former lover, who committed suicide by drowning himself. Chandraboti’s father suggested that she occupy herself by translating the Ramayana from Sanskrit to Bangla. Chandraboti started the work but died before she could complete it. Dinesh Chandra Sen included Chandraboti’s Ramayana in Purbabanga-Gitika. The following is a transcreation by Nuzhat Amin Mannan of poet Nayan Chand Ghosh’s Chandraboti. |

Chandraboti

1. Dear Alien

Do women not carry water

From where you come?

Are river banks not allowed

To the female sex!

Do men bring in the drinking water, carry the vessels?

Have your forefathers always scolded you for

Looking at a woman?

Is it unbearable the thought of a woman touching water,

water that gives life… all too precious

to be trusted in the hands of women…

by the way where is it that you come from?

Over here women go to the river everyday,

And no ones stares the

The way you did today!

|

2. Divinest Chandraboti

I do not know

What women carry or do not carry

at home or in other parts of the world.

I cannot have lived at all

Not having seen, before yesterday, you Chandraboti.

Oh, was there a river too??!

Where I come from

Women are sweet, docile, tulsi-tending, husband-worshipping

Son-giving, everything a man could ask for

And did I still stare at Chandraboti?

I did IF she made me

Stare

Or breathe

Or live

Or die.

Yours, Joydev

|

3. Dear Joydev

How thoughtful of you

To leave your letter

Among the flowers I had collected

For my father, the Acharya’s pooja!

Had I not had a wasp to displace settled among

that bed of white jui and crimson hibiscus

how would I have known that

an alien whom I may now call Joydev

not only stares

but also snoops

on women unawares!?

You must try harder Joydev.

I read a little and

Do not easily

Swoon

at sweet nothings

Specially those

From men

Who know what artifice to use

To make menials of fawning women.

Truly, Chandra.

|

4. Chandra

Chandra fawn for me! So that I can make a menial out of Chandra?

Why mock me, Chandra?

I gathered that you read voraciously.

My artifices are simple

Naïve, a lot more down to earth

Than yours that you collect from your books

As a bee gluts itself on the honey it takes.

Tell me honestly,

Without artifices that make virgins virtuous…

Have you not felt as I

Unabashedly declare I did?

Did not your blood rush

to touch my letter,

I, the Snooper, did not imagine you turning crimson

I saw you, wet and trembling, standing among the morning dew

in a white saree, your hair like Meghdoot’s clouds.

I could have given my life to cling to the moment I laid my eyes on you,

Loving you, I did no wrong

If your dawn rituals are done out of obsequiousness to a God one cannot see

My rituals to follow Chandra, to worship her flesh and soul

should not appear unseemly!

Truly, Deeply, Madly Yours, Joy.

|

5. Sutra

I have professed I read a little

I have not, however, come across any Virgin’s Manual for Fooling Men!!

I do not know how to deceive whatever artifices I may possess,

I know of a simple sutra though

Written by a bachelor (?) sage.

The sutra proclaims that

Joy is ephemeral

And suffering real

What Joy gives easily (no puns here on your name)

Is taken away summarily on a whimsy.

Suffering is the more faithful love

Who sits, sighs, woos you to the end.

I trembled this dawn, Joydev, as I was cold,

Turned crimson because I felt caught

In fetters that I did not think existed for Chandraboti.

Yes, I am flesh and blood and everything in between that

Makes us weak and unwise!

You did not do anything wrong to love me because

No sanyasi’s sutra clouds your mind.

I on the other hand have been warned

And I know I am out of my mind

To tell Joy that I love him back.

-Bewildered, Chandra

|

6. Bewildered

I trembled too, Chandra, because I was hot

And not just with desire

But because I felt a bewildering sort of peace.

I pledge myself a slave to Chandra,

in dreams,

in waking moments and in slumber.

I will hold you, hold me forever too, Chandra

Mock me some more, tell me I am raving.

But banish sutras, my Chandra, that bewilder you

Be my wife, my mate, my soul!

Enraptured, Chandra’s Joy

|

7. Riverbank

Why do I tremble so, she is ravishing, I am hot

with desire

with a bewildering weakness, She’s exquisite, perfect!

I will hold you, woman without a name

Mock me, tell me I am raving, unfaithful

Remind me that I have pledged myself to Chandra.

No, banish such thoughts, this Moslem beauty that bewilders me

Shall be my wife, my mate, my soul!

|

8. The Bride-to-be

Oh this red is too red for me

And oh dear! must I wear those too

The filigree gold chains and anklets?

Pardon me, I can dress myself.

I know Joy wouldn’t care if his

Bride came in ashes or in alta

We will pay homage to the sacred fire together

And I’ll wear my vermillion and shanka

Only for Joy, my husband, my equal, my other self.

|

| 9. How’s that !

“She is extremely stupid, if I may say so

Imagine reading all those books, such a father’s daughter

Being so stupid!”

“Did you see her shed her gold chains and forget that her aanchal trailed?”

“And wipe all those alpanas we made with her dragging feet

Silly girl, to think men can be constant!”

“But Joydev marrying a Muslim

forsaking our ancestral Gods,

Isn’t that so over the top?”

“I knew this would happen, told her just as much!”

“Did you now, how come?”

“Strange you should need to ask.

Doesn’t falling in love tell you something

does it not have an ominous ring?”

“Oh, Oh, poor Chandraboti ,

what will she do, who will have her now?”

“Silly girl, to think men can be constant!”

|

10. Lost in Translation

Chandra, hate me

As I deserve

But I must tell you

Of my grief

I don’t know how it was

I married someone I did not love

And forsook, left my Chandra, shindoor-less

Waiting for me in her bridal wear.

Like in a foreign tongue,

Something incomprehensible

Was jibber-jabbering in my head

My heart, I wish…Chandra

You had left me my heart as an amulet!

My well-read Chandra,

Read in my unabashed anguish,

I love you more than myself

Translate my monstrous regret

As my sincerest protestations of love.

Sweet Chandra, hate me as I deserve

But have me back!

Jalal/Joy

|

11. Statue

This is not you

Chandra

The Gods have substituted

My Chandra with a blankness

stone for flesh

And stillness for breath

Ah! Chandra I know you love me still

But are blind to your Joy, to his fate, to his life!

I am raving, it wasn’t you, it was I who was blind,

Blind in love for Chandra, blind in my errant ways,

blinded now by your glistening reserve.

Tell me, Chandra, tell me you are human

Like the rest of us, that blemishless

Though you are, you understand

Frailty and Weakness, and Corruption

Not only as discourse,

but also as human passions

We are not statues or Gods

Chandra, speak to me one more time

And I will be gone,

Forever, leaving you

My unwed wife!

in your barren temple.

|

12. Temple Door

How quiet it grows all of a sudden!

How peaceful

How monstrous looks the dawn

Red, vermillion, gold!

Or may be it’s just my reddened eyes that makes it look so vile

Old temple threshold, hold me, protect me

Ancients guide me

What poor comfort my books are now

And you Gods that stare and stare

Chandra’s tears are too human to mean anything to you my Gods!

Well, here’s a new dawn

A fresh deluge of torture

Forget, remember, forget, and with ferocity remember

I had Joy and lost Joy and could have had him again!

No, he left me, left his Gods,

He wanted me, he repented his errant ways

No, he left me, left his Gods.

He wanted…Enough,

Women go to the river here every day

I can do it again.

How quiet it grows all of a sudden!

And how sharp the air is today

How cold the water’s touch

I tremble, Joydev, are you here? Bloated with peace at last?

Why, Joydev, the river? you always hated water!

|

Chandroboti- East Bengal Ballet -Original Text in Bengali

Back to Content

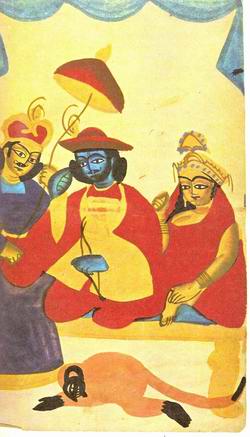

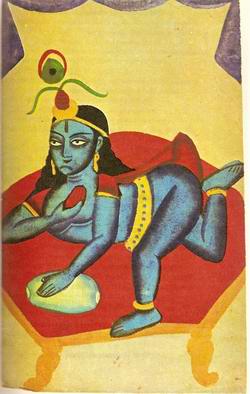

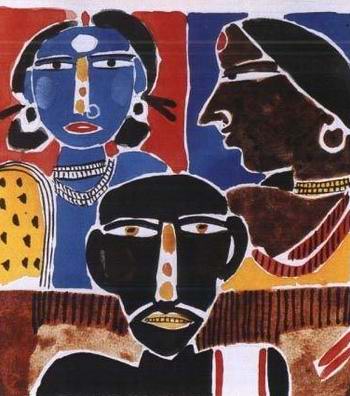

4.3 Sonai Bibir Pala A play glorifying humanism

The narratives of our rural bards are wonderful treasures of literature. Beer-narayaner Pala, derived from Purba Bango Geetika (East bengal Ballet), is a love story of a Hindu Zamindar's son named Beernarayan and an ordinary Muslim girl named Sonai Bibi. However, young playwright Raihan Aktar's play Sonai Bibir Pala, an adaptation of Beernarayaner Pala, is not just a love story. Through the tragic end of the central characters' affair, the playwright has dealt with a contemporary issue -- the conflict between religion and humanism. The narratives of our rural bards are wonderful treasures of literature. Beer-narayaner Pala, derived from Purba Bango Geetika (East bengal Ballet), is a love story of a Hindu Zamindar's son named Beernarayan and an ordinary Muslim girl named Sonai Bibi. However, young playwright Raihan Aktar's play Sonai Bibir Pala, an adaptation of Beernarayaner Pala, is not just a love story. Through the tragic end of the central characters' affair, the playwright has dealt with a contemporary issue -- the conflict between religion and humanism.

On September 10, the Centre for Asian Theatre (CAT) staged the first show of Sonai Bibir Pala at the National Theatre Stage in Dhaka. The show followwed on the heels of the premiere of the play last June 25, at the International Theatre Festival in Taipei.

To the acoustics of dhol and mandira, the troupe entered the theatre hall and recreated a procession on the stage. In the midst of the gathering, the gayen (bard) began narrating the love story of Sonai Bibi and Beernarayan.

Director Kamaluddin Nilu has not only used the narrative technique (the traditional form of pala gaan), he has blended several other theatrical forms as well. Particularly in the 'post-marriage scene', Sanskrit theatre forms like Parikrama (circular movement) and Patti (using of curtain) have been used. And in the composition of the 'Zamindar's court scene', the artistes have followed the typical rhythmic high-pitched voice modulation used in jatra.

The smooth transition of sequences in the play is the specialty of Nilu's directorial approach. Fifteen artistes on the stage have played different characters as well as given a choral rendering. There is a small interval during the transformation of 'characters' and 'choirs', which gave strength to the theatrical presentation. However, the blending of kirtan tune with palagaan was not effective.

Only a few stage crafts have been used. The light design is simple. Shamima Akhtar, as Sonai Bibi, enthusiastically threw herself into her role. Her body language, especially in the last scene when her beloved is being punished by his zamindar father, moved the audience. Young talent Shahadat Hossain was not in his best element. His spontaneous performance in the role of Beernarayan could have been more entertaining. The rest of the cast was impressive. In fact, Sonai Bibir Pala is a good example of teamwork (Daily Star, September 12, 2005).

|

Purbabanga-Gitika a collection of folk ballads of East Bengal. These ballads, composed orally and performed among the rural communities, are important resources of bangla literature. The ballads were collected from Mymensingh, Netrakona, Chittagong, Noakhali, Faridpur, Sylhet and Tripura. The main collectors of these ballads include chandra kumar de, dinesh chandra sen, ashutosh chaudhuri, jasimuddin, Nagendrachandra Dey, Rajanikanta Bhadra, Bihari Lal Roy and Bijay Narayan Acharya.

Purbabanga-Gitika a collection of folk ballads of East Bengal. These ballads, composed orally and performed among the rural communities, are important resources of bangla literature.

Purbabanga-Gitika a collection of folk ballads of East Bengal. These ballads, composed orally and performed among the rural communities, are important resources of bangla literature. The ballads were collected from Mymensingh, Netrakona, Chittagong, Noakhali, Faridpur, Sylhet and Tripura. The main collectors of these ballads include chandra kumar de, dinesh chandra sen, ashutosh chaudhuri, jasimuddin, Nagendrachandra Dey, Rajanikanta Bhadra, Bihari Lal Roy and Bijay Narayan Acharya.

Purbabanga-Gitika a collection of folk ballads of East Bengal. These ballads, composed orally and performed among the rural communities, are important resources of bangla literature.  Volume 1: Eastern Bengal Ballads : Mymensigh (1923), contains ten ballads:

Volume 1: Eastern Bengal Ballads : Mymensigh (1923), contains ten ballads:

Here it is useful to pay some attention to the works of Dinesh Chandra Sen, the pioneering historian and a lifelong devotee of Bengali literature.4 Once hailed as the foremost historian of Bengali literature, he was lampooned by a younger generation of intellectuals in the 1930s who faulted his sense of both politics and history.

Here it is useful to pay some attention to the works of Dinesh Chandra Sen, the pioneering historian and a lifelong devotee of Bengali literature.4 Once hailed as the foremost historian of Bengali literature, he was lampooned by a younger generation of intellectuals in the 1930s who faulted his sense of both politics and history.

In this month of Phalgun, householders sow the seed.

In this month of Phalgun, householders sow the seed.

Kishoreganj a northern district of Dhaka, is enriched with archaeological heritage. People are very proud of and talk a lot about their rich cultural heritage. Poems of Chandrabati are a hot topic. They talk very highly about Jangalbari, and about boating on the haor. We decided to visit Chandrabati's house Jangalbari.

Kishoreganj a northern district of Dhaka, is enriched with archaeological heritage. People are very proud of and talk a lot about their rich cultural heritage. Poems of Chandrabati are a hot topic. They talk very highly about Jangalbari, and about boating on the haor. We decided to visit Chandrabati's house Jangalbari.

Beautiful Chandrabati was in love with a Brahmin boy called Joychandra. The two were to get married when suddenly Joychandra jilted her for another woman. Chandrabati, heart broken decided to remain celibate all her life. Seeing her in such grief Chandrabati's father advised her to occupy herself reciting the Ramayana and in praying. Her loving father Dija also made a separate Shiva temple for her to pray next to his manasha temple.

Chandrabati devoted herself to reciting and, writing odes and in praying. Some of her well-known odes are: Malua, Dossho Kenaram and Ramayana Katha (incomplete).

Beautiful Chandrabati was in love with a Brahmin boy called Joychandra. The two were to get married when suddenly Joychandra jilted her for another woman. Chandrabati, heart broken decided to remain celibate all her life. Seeing her in such grief Chandrabati's father advised her to occupy herself reciting the Ramayana and in praying. Her loving father Dija also made a separate Shiva temple for her to pray next to his manasha temple.

Chandrabati devoted herself to reciting and, writing odes and in praying. Some of her well-known odes are: Malua, Dossho Kenaram and Ramayana Katha (incomplete).

Ancient wisdom, as handed down in the form of legends and folklore, offers the best escape route from the sufferings of a world full of unhappiness, discord and hatred. Being staged as part of Ganakrishti's annual theatre festival, Chandrabati is a simple tale of love and longing that inspires and re-awakens in us faith in the fundamental virtues and values of life. Based on a popular story from Maimansingha Geetika, a collection of centuries-old Bangladeshi pala (ballads), the play narrates the life of its eponymous protagonist. Friends since childhood, Chandrabati and Jayananda fall in love and decide to get married. However, impressed by the beauty of another woman, Asmani, Jayananda sends letters to her, expressing his feelings of admiration. Despite being aware of Jayananda?s pledge to Chandrabati, Asmani informs her father about Jayananda, and he is forced to marry Asmani. Shocked and betrayed, Chandrabati becomes a recluse and spends her days in worship, finally refusing a repentant Jayananda when he returns. Direction: Manish Mitra.

Event: Play in Bengali, Chandrabati, produced by Kasba Arghya (The Telegraph, July 23, 2005)

Ancient wisdom, as handed down in the form of legends and folklore, offers the best escape route from the sufferings of a world full of unhappiness, discord and hatred. Being staged as part of Ganakrishti's annual theatre festival, Chandrabati is a simple tale of love and longing that inspires and re-awakens in us faith in the fundamental virtues and values of life. Based on a popular story from Maimansingha Geetika, a collection of centuries-old Bangladeshi pala (ballads), the play narrates the life of its eponymous protagonist. Friends since childhood, Chandrabati and Jayananda fall in love and decide to get married. However, impressed by the beauty of another woman, Asmani, Jayananda sends letters to her, expressing his feelings of admiration. Despite being aware of Jayananda?s pledge to Chandrabati, Asmani informs her father about Jayananda, and he is forced to marry Asmani. Shocked and betrayed, Chandrabati becomes a recluse and spends her days in worship, finally refusing a repentant Jayananda when he returns. Direction: Manish Mitra.

Event: Play in Bengali, Chandrabati, produced by Kasba Arghya (The Telegraph, July 23, 2005)

The narratives of our rural bards are wonderful treasures of literature. Beer-narayaner Pala, derived from Purba Bango Geetika (East bengal Ballet), is a love story of a Hindu Zamindar's son named Beernarayan and an ordinary Muslim girl named Sonai Bibi. However, young playwright Raihan Aktar's play Sonai Bibir Pala, an adaptation of Beernarayaner Pala, is not just a love story. Through the tragic end of the central characters' affair, the playwright has dealt with a contemporary issue -- the conflict between religion and humanism.

The narratives of our rural bards are wonderful treasures of literature. Beer-narayaner Pala, derived from Purba Bango Geetika (East bengal Ballet), is a love story of a Hindu Zamindar's son named Beernarayan and an ordinary Muslim girl named Sonai Bibi. However, young playwright Raihan Aktar's play Sonai Bibir Pala, an adaptation of Beernarayaner Pala, is not just a love story. Through the tragic end of the central characters' affair, the playwright has dealt with a contemporary issue -- the conflict between religion and humanism.