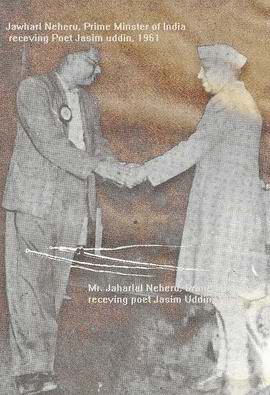

1.Jasim Uddin by Barbara Painter, Washington DC, USA, 1969

Jasimuddin - Poet of the people of Bengal-

A film by Khan Ata 1978Jasim Uddin was born on January 1, 1904, in a small village, Tambulkhana, in the Faridpur district of East Bengal. That was his grandparents village, only eight miles from his parents home in Govindapur. He has described these two villages and their manner of life in his autobiography. Many scenes from The Field and Gipsy Wharf have their setting in these villages. In those books Jasim Uddin is writing of a time when the land of Bengal had fewer problems than present day East Pakistan, with its overpopulation, influx of refugees, chronic floods, epidemics and food shortages. He likes even now to think of those happier days, and writes:

'In every household there were milk cows. Those who did not have cows could go to a neighbour's house and ask for milk. Sitting on my blind great under Danu Mullah's lap as a boy, I used to listen to these stories of ease and prosperity. In my books Nakshi Kathar Math (The Field) and, Sojan Badiar Ghat (Gipsy Wharf) I was remembering the peoples of these villages. Even today this picture of plenty in the villages gives me pleasure when I think about it. Ir I could but change this joyless, needy land of today with all its prejudice for that land of happiness, song and prosperity, I would dance for joy (Jasim Uddin, Jibon Katha, 1964)

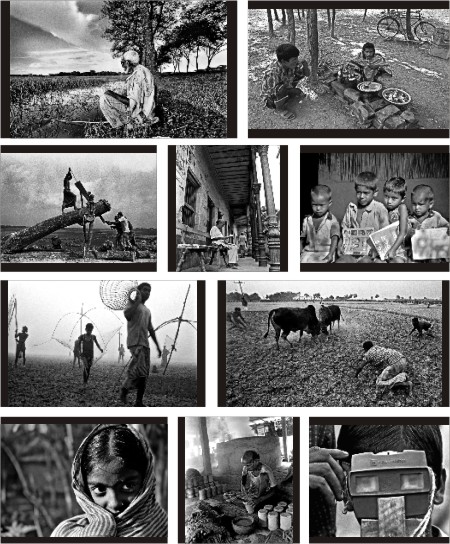

It is the picture of the contented farmer living on his fertile land that gives Jasim Uddin the most pleasure. The heroes in his books either are farmers, such as the boy Rupa in The Field, or the illiterate hero of his novel Boba Kahini, or like Sojan of Gipsy Wharf they want to be farmers. Though his own father did not have much land Jasim Uddin had the satisfaction of knowing that many of his ancestors were prosperous Bengali farmers.

He writes of one in particular, a certain Aradhan Mullah, 'I have heard that Aradhan Mullah was a large land-holder in the village. He was very well to do. He owned fields full of sugar cane. When this cane . was cut the stalks were crushed and juice extracted; the juice was boiled into syrup. The vendors used to carry thousands and thousands of pounds of this syrup in pots hung from shoulder yokes. When they passed through the village carrying it from Aradhan Mullah's house to the markets and bazaars, the village ladies used to come out of their houses to watch. A guest or traveller was never turned away from that house. Stored in his counting house were huge baskets full of fried rice, sweetened rice and coconut confections. Whoever wished could co me and eat. Sometimes at his house as many as two or three hundred people would eat with his family.'(

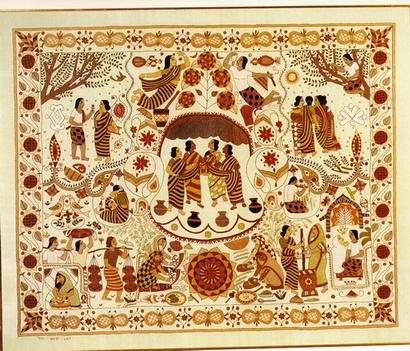

It was a land of plenty in those days with no need for much money or hard work. One might say Laksmi, the goddess of wealth, smiled on Bengal. 'In former days, in every quarter of the village there were song gatherings, Gajir songs, Jari songs and Keccha songs, which kept the villages in a state of excitement. The fields yielded good harvests. With a little scraping of the plough and a flick of the wrist to sow the seed broadcast, green sprouts appeared covering the paddy fields as far as the horizon. The rivers, canals and ponds swarmed with fish. One had only to scoop them out by hand., Very few things were bought with money. For a few sheaves of paddy the blacksmith would forge a plough, the barber would cut hair, the,potter make pots; for a little mustard seed little oil presser wouver mustard oil to every horne. Even now this method of bartel' is in use in the villages.'(Jibon Katha)

These recollections of a happier land, told Jasim Uddin by his blind relative, are, perhaps, doubly attractive to the poet because of the needs of the overpopulated hungry land today valid because as a boy Jasim Uddin knew what it was to be be hungry. He writes:

When I was a boy I had no fine clothes to wear. I did not have winter clothes sometimes, but I do I do not think that I felt any particular sorrow on that account. For no other thing do I blame my mother and father except that, when I was a growing boy, I was driven to seek out those sweet and wholesome foods my body required, looking in the forests and jungles for this or that fruit. When at someone's house rice cakes were being made the housewife would give them to her own boys and girls, then to everyone else. I used to hope after one plate was empty she would ask me to have a cake; one plate was empty, then another. Still the housewife did not look at me. So, heaving a great sleigh, I returned home (Jasim Uddin, Jibon katha, 1964)..

For, when Jasim Uddin was a boy, his family was very poor. His father was the teacher in the village school, a very (dedicated man who sometimes earned only seven rupees a month. Later he became the mullah, the religious leader of the Moslem community in the village. In Jasim Uddin's Own words:

My father's uncle, Jahir Uddin Mullah, was the mullah of our village. For same reason or other he left the country to go to Malda (a village in West Bengal near (Calcutta), and the responsibility for the, office of mullah fell on my father .... If there were a wedding among the farmers of the village father would receive from one to three rupees. ... In the estimation of the village, father now held a position of leadership (Jibon Katha).The poet asserts he gathered material for his plot from actual happenings in his own Faridpur district. 'Iri our Faridpur district there live many poor farmers, Moslem and Namasudra (Hindus). Almost continuously there is a quarrel among them over some insignificant incident. In all these quarrels the wealthy Hindus and Moslems encourage them and drive them down the path of dis aster. Among the rich and the landlords there is no distinction of caste. In the world of the exploiters all are of one dais. If one could see the condition these unfortunate NNamasudrohmasudras and Moslems are left in by the oppression of these people, one could not hold back tears from one's eyes. With just such incidents the plot of this book is constructed.'l

Jasim Uddin's mother brought her family through some difficult days. She was the only woman in the house, which is unusual in Bengal. There were no grandmothers,spinster aunts or other female relations to help her with the housework. When his mother, Ranga-chhutu, wanted to make the rice cakes the boy Jasim was so fond of, she rose before dawn to husk the paddy. When she went to the cooking shed her son sometimes accompanied her. He would sit near her waiting for the first rice cakes to be ready. There is a compliment he pays her cooking:

'To myself I kept praising my mother. My mother knows so much. Receiving the magic touch of my mother's hand, the bits of rice and treacle would become such delicious rice cakes and be transformed into something new. This is the task of every artist. He takes what he has to work with and, manipulating it according to his liking, gives it new life (Jibon Katha.

]asim Uddin's mother came from the village of Tambulkhana. Though only eight miles from the larger village Govindapur, Tambulkhana was almost in the jungle. ]asim Uddin writes of it:I have heard long ago there was no jungle in that place. The prosperous farmers lived in well built bungalows. The village teemed with people. Then there was a cholera epidemic and many fell sick with malaria as well. Where an orchard once flourished, bamboo and vines and creepers began to grow so thickly they made the spot unfit for human habitation. Then jackals, polecats, wild boar, tigers and other animals gradually made their horne there. The farmers who did not move their houses and goods far away had to fight a continuous battle with the wild beasts.(Jibon katja, 1964).

While on a visit to Tambulkhana as a boy, he recalls how a tiger came one night and prowled around their cottage. This village of his grandparents was an exciting place. He enjoyed accompanying his mother there, walking alongside her bearer-born palanquin down the jungle paths.

In spite of his poverty, ]asim Uddin spent an interesting childhood. Recalling those days he writes:

'I look back as far as my gaze will go to the first scenes of the far past of my life. In that land of light and shadow so me things are clear, so me hazy; a few pictures come floating to my mind. On a rainy day, having spread an embroidered quilt on the floor, mother is sitting there sewing. She is humming a tune. . . . Father, rising before dawn, is reciting the prayers. From his throat the intonation made an incomparable impression on my half-asleep boy's mind such that I can never express in words .... Standing at the door is a fakir who wears a string of fiery beads around his neck. He is singing from the book of ]oseph and Zuleka .... After I had played the whole day, and my body was covered with mud and earth, I would return home at sundown. Catching hold of me, mother would wipe me clean with her own sari .... Across the whole sky a storm was raging. Thunder crashed with loud peals. Lying in bed I clasped my arms around father's neck .... All day there was a cloudy sky. Light rain was falling continuously. In the reception room of the landlord, uncle was reciting from a book. I had not yet reached the age to understand what he was intoning. The sound of the recitation mixed with that of the falling rain brought so me kind of detached feeling to my mind .... And just such very small memories come to my mind like pictures. Many very important happenings I have forgotten; but when I find time these pictures come and play on the theatre stage of my thought.

]asim Uddin has, woven some of these memories into his writing. The heroine of The Field of the Embroidered Quilt sews her story on just such a home-made village quilt. In Chapter 4 of Gipsy Whraf the ghosts scatter and the boy Sojan is awakened from his dream by the morning caU to prayer.

In his autobiography ]asim Uddin tells much more about village life as he knew it. He swam in the ponds and canals, fished in thc rainy season, watched the sugar cane being made into treacle, and ate his fair share of this tasty sweet. The boy Jasim built a banana-palm raft and sailed it one early morning to help hirnself to a neighbour's ripe dates. Like his hero Sojan, he knew ,where the weaver bird made its nest and admired the intricate construction. He knew when and wherc the best mangoes and plums were ripe. When the travelling theatre, the Jatra, came to town he and his cousin, Nehaj Uddin, would sneak off and stay up all night listening lo the play. Throughout the year they enjoyed both the Hindu and the Moslem holidays .

In most ways his life as a boy in Bengali villages was like tbat of other boys. He had, however, a most unusual friend, a Hindu ascetic, a sannyasi. The sannyasi came one day his hermitage (called an asram) on the outskirts of Govindapur near the Hindu cremation ghat.

Soon this holy man had many followers, but none more ardent than the small Moslem boy, Jasim. He listened attentively to the sannayasi reaeling the Hindu scriptures. He took pleasure in teneling the fiower garden whieh surrounded the little asram, a necessary adjunct as flowers are used in worshipping the goals. He even cleaned the asram. The sannyasi in turn taught the boy the Hindu scriptures which, like the Bible, are full of exciting stories. He taught him many disciplines and meditations; one which Jasim Uddin mentions praetising was how to overcome sensitivity to cold. The boy was very devoted to this guru (teaeher), and when the sannayasi left the village to make a pilgrimage to the Himalayas, Jasim was very disappointed that he could not accompany him.

For the friendship of the sannyasi and the insight he gave " him into Hindu culture, Jasim Uddin is still grateful. It seems to me his broadmineledness and sympathy for Hindu as well as Moslem tradition are among his best qualities as a writer. Gipsy Wharf is almost a plea for better Hindu-Moslem relations. Certainly he believes that the bonds which unite Bengali people are very strong, and the culture they have, made is both Hindu and Moslem.

Thanking the sannyasi in another passage, Jasim Uddin writes:

When I must give up something today it is not difficult for me to do so. Besides this discipline, the knowledge I obtained when a boy, of the Hindu gods and goddesses, of the method of accomplishing tasks that at first seem impossible, has helped me immensely in my creative work. The literature of this land (Bengal) is not merely Hindu literature, nor can it be said to be a Moslem literature. Since both Hindus and Moslems have written in one language (Bengali), the literature of this land is both Hindu and Moslem. Those who would separate the two and make literature will not last many day, I am sure. Because of the universality of appeal in the world of literature, sectarian thought is out of place there. If my own writing has achieved anything of universal appeal, then it is thanks to that sannasi' (Jibon Katha, 1964) .

The sannasi probably had the strongest influence of any person outside his family on Jasim Uddin. The boy did, however, have other friends who helped him, particularly with his poetry. His interest began when he was very young, perhaps seven or eight years old. He writes:

'Once I went to Samsmsundarpur for my uncle's wedding. This village was almost six miles from our village. On the following morning I rose early and in the distance heard the sound of drumming. When I asked about this I learned that in the neighbouring zamindar's estate-office there was a ballad recitation in progress, and the sound of the drum-beat was coming from there. I followed the sound of the drums and gradually came , closer to the estate-office. As I approached I heard also the inistinct tone of singing along with the drums. That tune drew me as in a dream towards the ballad recital.'

All during the uncle's wedding proeession the lines from the song recital kept running through his mind. As he walked along with the rest of the wedding party, escorting his bridegroom uncle's palanquin up and down the winding roads to the bride's house, the small boy sang aloud snatches from the ballad recitation he had heard.

When he returned to his own village he sought out one of the local poets to engage in a little song contest like that he had heard at the estate-office. He writes,

I have spoken before of Rahim Mallik of the weaver's quarter. Because he is a man of my village I call him uncle. He can compose ballads with little effort. Early one morning I went to see him and said, "Uncle, I want to have a ballad contest with you." '

So the weaver put aside his work and had a contest with the little boy. The weaver composed a ballad which consisted mostly of jokes about things that happened in the village. Then the boy Jasim sang snatches from what he heard at the recital, adding his own lines to that.

At the time of the contest with the weaver Jasim Uddin had no idea he was composing poetry. He was reciting what he had heard and adding his own words in the same tune. He says of that time, 'It was still my belief that books and poetry, like earth and sky, were there from the beginning or else God Himself had created them. Could man make such things!

When he discovered that he was composing poetry Jasim Udein made some effort to write it in a notebook. At first he had some difficulty: 'I had heard that poems had fourteen syllables in every line, and in the first line of a couplet the last syllable rhymed with the last syllable of the second line. Taking up pen and paper I thought and thought but could go no further. Sitting on the river bank I remained gazing at the sand bank on the other shore, but I could not compose a fourteen syllable line. Now and then I was so angry I tore my hair.

'One day It suddenly occurred to me; how would it be if I wrote the words in my notebook in the same ready manner that I composed oral poetry? After writing three or four of my couplets in the notebook I was astonished. There were fourteen syllables in every line and the last syllable of every line rhymed with the second line's last syllable. I doubt whether Columbus discovering America felt such joy as I felt at this discovery. For so many days I was accustomeel to composing my verse to a tune. Without a tune I could not compose the words in poetical metre. Now that I discovered how to find the rhythm for my verse, who could hold me back? I filled notebook after notebook (Jibon Katha, 1964).

Still another teacher Jasim Uddin mentions is Madhu Pandit:

'I only remember something he said one day. I had asked the Pandit, "I want to write Bengali books. You give me some good advice. What shall I do to succeed in this?"

Laughing he replied, "You are a Bengali boy. Whatever you write will be Bengali. For that there is nothing you need do. Whatever you have to say, write it in the same manner as Oll are talking to me. That will be your best composition." AlI my life I have tried to apply the advice of this pandit to my work.(ibid)So, at the age of eight he strated composing his own poetry. When he was still a young lad he visited a dramatics club in Faridpur:

Watching the theatre rehearsals over and over some of the passages of the plays by heart. Standing by riverside in the evening I would recite them in a loud voice. People used to call me mad Jasim (Pagla Jasim). In this manner, reciting one play after another, my weak voice became quite strong. I also learned the art of raising and lowering my voice effectively.

Many times the boy did not have the money to buy a theatre ticket, but he found a way to see the show:

Climbing thehe betel tree, shivering and trembling in the cold, to watch the play. In this manner I saw the plays :Shahjahan, The mogul Pathan, Shonay Shohaga(A Happy Marrage), Raja Harislz Chandra and others. Now and then or crook I got a pass for one or two days' performance. On those days I tried to memorize the whole of the play. Going to the river bank the next day I recited my lines like the characters in the play.1t appears that Jasim Uddin had the makings an actor as well as a poet. In later years, when he was a civil servant, he used to make speeches (educating villagers) for the government in the villages and proved such a good speaker that his audience of village people numbered thousands.

Thus Jasim Uddin started reciting and composing poems at a very early age. By the time he was a student at Faridpur Rajendra College his poetry had already won him some fame. Kobor (Graves) was prescribed as the text for the Matriculation Examination at Calcutta University when Jasim Uddin was still a student in the 1. A. Class (Rajenra College, under Calcutta University)

Jasim Uddin is proud of belonging to the folk tradition of Bengali literature. He was pleased by a recent comment of one critic who, praising his autobiography, said: 'Reading Jasim Uddin's Jiban Katha (autobiography) is like eating country cakes from mother's own hand.'

In a foreword to the translation of Nakshi Kathar Math, Mr Verrier Elwin writes, 'I do not know whether The Field of the Embroidered Quilt can be classed as folk-poetry, but it is obviously poetry about the folk. After nearly ten years of village life I find every detail of the picture, every turn of the story, waking a response in my mind.' What Mr Elwin says of The Field can also be said of Gipsy Wharf. The two poems were written within four years of each other, while Jasim Uddin was still at Calcutta University, doing research under the famous Bengali scholar, Dr Dinesh Chandra Sen. Gipsy Wharf benefited from Dr Sen's comments as well,as those of the famous writer and painter Abanindra Nath Tagore.

There were influences on Jasim Uddin's writing other than folk songs and ballads. Perhaps that is why some hesitate to call hirn a folk poet. He is also a scholar and for many years was a lecturer in Bengali literature at Dacca University. Then during the war he was summoned by the British Government to serve as a civil servant (Jasim Uddin, Prathom Alo, January 3, 2003).

The earliest influence on his poetry, however, was a group of minor folk poets of Bengal. He mentions them as his first teachers: 'From Rabindranath [Tagore] on down many critics have said the flow of my verse is very easy. If that is a virtue then I have learned this from our country's uneducated and half-educated poets. They are the first teachers of my poetic life, the poets Jadab, Parikshit, Ismail, Hari Patani and Hari Acharya. Into every rural househöld of Bengal they have poured an immortal flow of nectar. Deprived of that the Bengali heart would be a dry wasteland.'(Jasim Uddin, 1964).

Hindu and If Jasim Uddin's writing has benefited from influences other than these rustic poets of Bengal, that has in no way made hirn less an expert on Bengali village life.The poet asserts he gathered material for his plot from actual happenings in his own Faridpur district. In our Faridpur district there live many poor farmers, Moslem and I (Hindus).

"But from my boyhood to the present day for the love aud affection which I received from the sannyasi there remains a love and respect in my heart which has not in the least bit been destroyed.For the friendship of the sannyasi and the insight he gave " him into Hindu culture, Jasim Uddin is still grateful. It seems to me his broadmindedness and sympathy for Hindu as well as Moslem tradition are among his best qualities as a writer. Gipsy Wharf is almost a plea for bettel' Hindu-Moslem relations. Certainly he believes that the bonds which unite Bengali people are very strong, and the culture they have , made is both Moslem and Hindu.

Gipsy Wharf and The Field, I think, are among Jasim Uddin's major work, but he is a versatile and prolific writer. Like another famous Bengali poet, Rabindranath Tagore, Jasim Uddin has tried his pen in almost every field. Boba Kahini (Tale of an illiterate man) 1964 . He has written many short dance dramas: Beder Meye 1951 (The Gipsy Girl), Madhumala 1956 (from the fairy tale of Princess Madhumala), Palli Badhu (Village Bride) 1956, the plot of which, he writes, is borrowed from Tagore. Jasim Uddin has also collected and rewritten numerous folk tales and folk music (Jari Gan, Murshida Gan He has published two volumes Bangalar Hashir Galpa (Laughing Tales of Bengal), vol. I, 1961, vol. 2, 1964. Among Jasim Uddin's song books, perhaps the best are Rangila Nayer Majhi (Boatman of the Gay Boat) 1933 anel Padma Par (The Banks of the Padma River) 1949. Foremost of his lyrics are the books Rakhali (Pastoral Poems) 1929, Balu Char (The Sandbank) 1930, Dhan Khet (The Paddy Field) 1932. Other important lyrics written recently are in the books Rupavati 1946 and Sakhina 1960 (both girl's names). Thc first book of lyries published after the partition of India-Pakistan, when the poet moved permanently to Dacca, was the book.Matir Kanna (Sorrows of the Earth) 1955. This book has been translated into Russian.

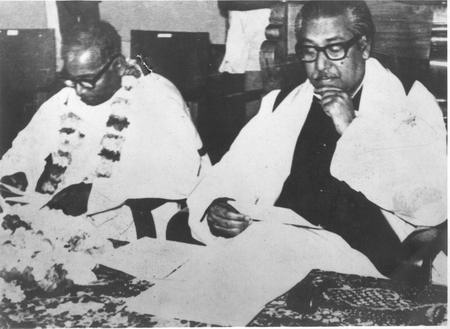

Barbara Painter, Washington, USA 1969Jasim Uddin resided at Jorashako, Kolkatta his best friends are Mohonlal Ganguli, Abinranath Tagore etc. 1929-33

On Translation, and on translating Jasim Uddin

To embark upon translation is immediately to come face to face with a crisis of conscience. Either one intends to take the scholarly approach of being absolutely faithful to the text, 0r else one means to be faithful to the spirit of the work.

This latter is the one I have favoured for this work, and I am guiltily conscious of how wide a field of potential error lies therein. Faced with an Eastern text to be interpreted for "Western eyes, the problem is increased, especially since my job has been to impose literary form at second hand.

I have been greatly indebted to Mrs Painter for the very thorough job she has made of reducing the Bengali to English with a wealth of annotation, and am loath to have her blamed for what some may take as cavalier attitudes on my part.

For my objective has been to please the general reader, to make a living work of a verse-novel whose themes are vital to the understanding of the peoples of the Indian sub-continent and, especially at these times, to the cause of peace. Such themes should take us beyond the littlc questions of grammatieal equivalent and exaet synonym.

Yann Lovelock, Sheffield, June 1967Jasim Uddins's most favourite fish - Hilsha Fish- Tenualosa ilisha

Jasim Uddin writes in his autobiography that when his father bought Hilsha fish from the market, this was a festival in their house. The day Jasim Uddin died he bought Hilsha fish from the market and hilsha fish curry was his last meal

During my (Chitrita Banerji,Eating India: An Odyssey Into the Food and Culture of the Land of Spices," published by Bloomsbury USA, 2007) years as a food writer, I have championed the cause of regional cuisine as the only authentic culinary identity. I have scoffed at the mere mention of "Indian" food or curry powder, which I came across often enough in America. Yet it is becoming more and more apparent, even from faraway America, that an inevitable fusion of influences from disparate areas is changing the nature of regional foods and eating habits in India today.

And in fact, there is nothing new about this trend. The same Bengali cuisine that I wanted the world to know and appreciate, instead of focusing on the ersatz curries and tikka masalas available in Indian restaurants everywhere, has also evolved and changed over the centuries. Even a casual look at the pages of Bengali narratives going back to medieval times shows significant differences from the way we cook and eat in Bengal today. With the passage of the centuries, Bengali cuisine has eagerly taken and absorbed exotic ingredients, and repeatedly been modified by external influences. The same is true of other regional cuisines in the subcontinent.

Bengalis love fish. Mention Bengali food to anyone in India, and the first image it evokes is that of fish and rice. Geography is responsible for the traditions -- from a high aerial perspective you can see Bengal (and historically, this includes both the Indian state of West Bengal and the country of Bangladesh) as an enormous delta in the eastern part of India, crisscrossed by rivers and rills too numerous to count. The smaller ones join up with the major rivers like the Ganges, the Padma, and the Brahmaputra, but eventually, they all find their way into the salty waters of the Bay of Bengal. On the map, you will see the emptying out of this collective water pitcher identified as the Mouths of the Ganges. Fly lower down, and you see the land that makes the delta -- alluvial soil, renewed every year with the silt deposited by flooding rivers, precious as gold to the farmer. The presence of the rivers and the lakes and the rich coastal waters bordered by the mangrove forests of the Sunderbans, have automatically made freshwater fish a major part of the Bengali diet. Moreover, fish here, as in many parts of China, is not merely food. As a symbol of prosperity and fertility, it touches many aspects of ceremonial and ritual life.

HILSA Tenualosa ilisha King of Fishes - Going to Extinct?

Imagine a scenario hundred years from now. The curator of Dhaka Museum is showing a skeletal remains of Hilsa fish, a recently extinct species, to the visiting school children. The once glorious novelty and mouth-watering delicacy Hilsa fish -- a delectable entrée of any common Bengali's dinner -- is completely lost in oblivion. The extinction of Hilsa and a great many other fishes and aquatic lives would be a fait accompli, if a wrong decision is executed by the Indian leaders. According to the recent media reports, a grandiose River Linking Plan is being seriously considered by the ruling BJP leadership of India.

The plan's formal announcement is not yet made. Neither is the detail released to the public domain. The would-be affected neighbouring governments of Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan are ignored and not even consulted. Sifting through the sketchy information from Indian NGOs and western news media, we can sense some aspects of the River Linking Plan and its horrific consequence on India itself and other co-riparian neighbours, especially Bangladesh.

Because of its gargantuan negative consequence on Bangladesh, we should voice our serious concern over this notorious plan and do everything necessary to stop this project. In this article I will address the following questions: what is the project all about and what would be its impact on aquatic life, especially the Hilsa fish of Bangladesh?

The change in river load will drastically change the ecosystem of Bangladesh, wrecking havoc. The runoff from the Indian agricultural land will be contaminated with herbicides, insecticides, and fertilizer. The wastewater disposal from Indian industries will unleash chemical contaminants in downstream rivers, and Bangladesh will be in the receiving end. The diversion of one-third water from the eastern river system will dry-up and silt-up many rivers in dry season, and then over discharge from Indian dams during monsoon will flood the silted rivers. The over-all scenario of Bangladesh will be a cancer alley where death and destruction will loom with impunity, and our favourite Hilsa will be a shadow of the past. (Source: Mostofa Sarwar, Ph.D,. University of New Orleans, USA. , Sept 19, 2003) .

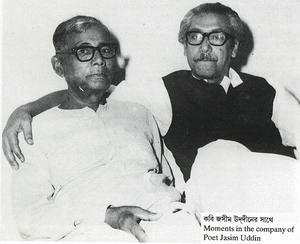

Home2. Memories of Poet Jasim,Uddin by Mary Katherine Donaldson, Boston, USA

Through friendship with Begum Momtaz Jasim Uddin I became aquainted with her husband, Poet Jasim Uddin. She was my tutor in Bengali the year I taught Art History in Dhaka, then Dacca, East Pakistan, in- 1963-64 on a Fullbright Grant from the United States. She often had complimentary tickets to Tagore plays given to her husband and would invite me to go along, since he could not go. The number of complimentary tickets he received indicated hi sprominence in the dramatic arts. Then Mrs. Jasim Uddin invited me to dinner at their horne, where I met him and their daughters Hasna and Asma (a little girl). Soon I was a regular visitor.

Mr. Jasim Uddin was a poet of the people. He had been a disciple of Tagore and lived in his house for three years. Often hc went to folk performances that lasted all night, and he was very generous to poor poets and musicians. (If it hadn't been for Mrs. Jasim Uddin he would have given everything away before the end of the day.) English translations do not always convey the extent of his folk appeal as emphatically as his own words, although he did not consider himself f1uent enough to write in English.

For a time, until thc interruption of the riots, I 'translated' his poetry for him - he put it into English and I polished it. And I learned that when he had said 'she feIt like a lady bug crawling around her bangle', it had been translated 'She feIt like a butterfly.' When he had said 'Her hands were smooth as a bunch of bananas', it had been translated 'Her hands were like a lily.' He argued that the translation was good if it conveyed the feeling of joy and beauty, but said that anyway the poverty of the english language, which had one word for all kinds of love, distributed in some twenty seven in Bengali, made translation of his poetry impossible.

The power of Poet Jasim Uddin's poetry, prestige, and personality was sorely tested the year I was there. A hair said to be of the Prophet was stolen to the north in Nepal, and riots ensued. They began with West Pakistani workmen in the jute mills, but soon spread. Many Hindus, who were accustomed to living peacefully with their neighbors, were killed and much of the Hindu culture in East Paki stan was destoryed.

Poet Jasim Uddin and other gurus among the poets went out into the midst of raging mobs with words of peace. Often with Bengali sayings such as

'Many cows, one milk' he would quiet angry mobs, and he would exhort them,

'Are we idol worshippers, that we should worship the hair of a head?'

Other poets who tried the same things were killed, but he survived despite threats with which Begum Jasim Uddin was bombarded on the phone at horne.Governing bodies recognized his pre-eminence. He received a pension from the government as a Poet Laureate. When Chou En lai, Premier of China, visited Dhaka, he was entertained by Poet Jasim Uddin's play. In thanks Chou En-Iai sent hirn a beautiful chinese silk robe embroidered with dragons and some rare tea. (When they shared the tea with me the Jasim Uddin's wondered whether the Premier would approve, since America was not yet on diplomatie relations with China. This was the first year of that country's opening to the West after years of isolation.)

And, Momtaz told me on a later visit to the U.S., when a new country was born Poet Jasim Uddin was asked what it should be named, and he answered 'Bangladesh.'It is altogether suitable that a festival and a folk and poetry center are to be established in his memory. Jasim Uddin would also have been pleased to have such a center a museum and market for the folk arts, a place where the bengali woman can get her sari of Dhaka Jamdani, her husband can buy a book, their children can pick up toys.....

. It would be nice to have a miniature of an embroidered quilt, such as one of the many mementos Momtaz has brought me, beside Poet Jasim Uddin's book of the permanent display in the Folk Arts Center named after him. It has been a privilege to know Poet and Mrs. Jasim Uddin several members of their family for almost thirty years, even through several members only lived in Dhaka for one. Best wishes to all of you!

Pride of Performance is one of the highest civil award given and conferred by the Pakistan Government to Pakistan's citizens in recognition of distinguished merit in the fields of Literature, Arts, Sports, Medicines, and Science for civilians in most particular cases. The announcement of civil awards, including Pride of Performance, is generally made once a year on Independence Day (14 August), and the investiture ceremony takes place on the following Pakistan Day (23 March) by the President of Pakistan. The Pride of Performance award has no particular standing in Pakistani civil decorations hierarchy, but is regarded as one of the highest honours in Pakistan. Pride of Performance is a civil award given by the Government of Pakistan to Pakistani citizens in recognition of distinguished merit in the fields of literature, arts, sports, medicine, or science for civilians

Kavi Jaseemuddin in 1958 obtained Pride of Performanc (First Award in Pakistan) for- Literature -Poetry -East Bengal- East Pakistan (now Bangladesh)

3. Visit Jasim Uddin House, Ambikapur, Faridpur

Graves

Here, under the pomegranate tree, is your grandmother's grave;

For thirty years my tears have kept it green.

She was a little doll-faced girl when she came to my horne,

And she wept to be done with the play ofher childhood days.

Returned from my travelling onee,

I suddenly knew She had been in my thoughts all the time.

Like the dawn her golden face would blind my eyes,

And from that day I lost myself among small joys of hers.Black is the ink in my inkpot, from the pen with which I write:

Black is the pupil of my eye with which I see the world.

KUMAR RIVER, Ambikapur - THE RIVER OF SORROW

Fayza Haq

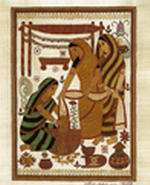

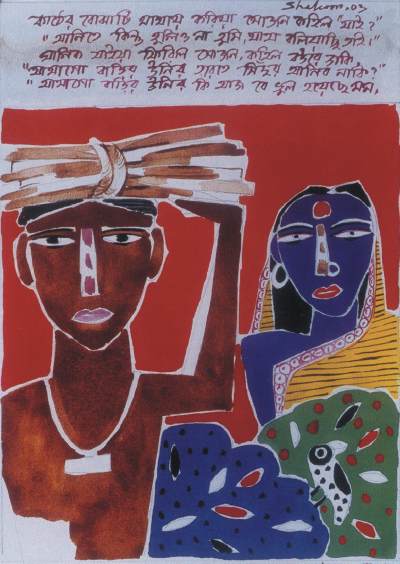

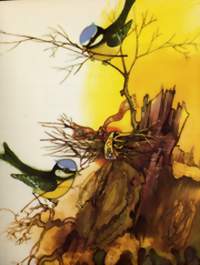

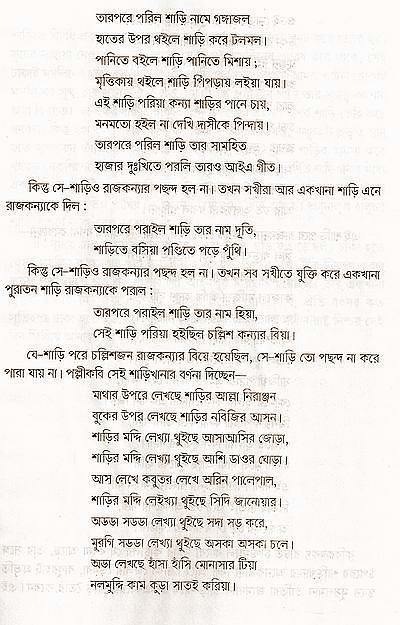

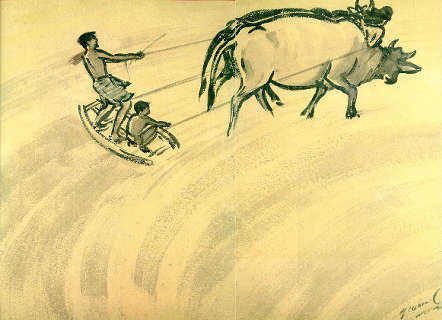

Abdus Shakoor Shah, talking about his ongoing exhibition said, "It was Shubir Chowdhury of the Shilpakala Academy who decided the subject. I spent three months over it. There is some experimentation here for I had to deal with Jasim Uddin's 'Shojon Badhiar Ghat' and 'Nakshi Kanthar Math' as there are characters here like the go between in a marriage and protagonists like Dulali and Sujon and their love affairs. There is the presentation of the 'lathial' and other important personalities called Saju and Rupa. The subject has differed somewhat while I used water, acrylic and oil as before. Thus it is the composition which has changed from before such as when I've put my subjects in a round circle. I did this to bring a variation in my work. However, the vastness of the poems is such that I felt I could not do justice to them in the short time given to me. It would require about seven years to treat the subject adequately. I have treated the subjects briefly and with the help of symbols."Asked to elaborate on his symbols, Shakoor said, "I have presented the ways the poetry has described the girls such as with dark skin but inimitable beauty, the birds have come in standing for freedom, the thatched huts are there with banana trees standing for peace and harmony. The influence of older relatives like uncles and aunts have come in to show strong family bonds that characters like Saju and Rupa enjoyed in their lives and which is there even today in rural existence. The plot of 'Nakshi Kanthar Math' however is a vast canvas that requires at least a year from an artist like myself."

Speaking his treatment of his subjects, Shakoor said, " 'Nakshi Kanthar Math' deals mostly with love affairs. It brings in the setting of a vast area, which I've been unable to bring in. Saju for instance is seen speaking with her father discussing her love and marriage. Again, in 'Sujon Badiar Ghat' there are important characters like Dulali and her friend talking together which I've delineated in a red circle along with leaves and birds. I've used black and blue to bring in the complexion of the bronzed beauties in the villages." Touching on how he formulated his particular style, Shakoor said, "For six years now I've been bringing in the impact of folk art in my work. I did work of that type at times before but I did not have it uppermost in my mind that I should reflect Bangladesh, its language and its culture in my work. While working on this particular theme of Jasim Uddin's poetry I've had the fear that the work might be illustrative which I didn't want. In order to bring in the quality of painting I've maintained my old style keeping in mind the surface and the composition. As for the lettering it is a part of the poems that the paintings are about. I do not consider it as calligraphy as in that one plays with the shapes of the lettering, and forms designs and motifs with them. The writing, however, is an integral part of the composition of the paintings. Calligraphy, on its own, can be an art by itself."

Continuing about the use of flat colours with the contrasting blues and reds, the delineation of the clothes and jewellery, Shakoor said, "I want the viewer to straight away say that he is viewing a Bangladeshi work when he/she sees my painting. I want to maintain my Asian identity and revel in the flat surfaces. The colours are bright while the heroes and heroines are black or blue or even brown and gray. I've been influenced by the works of Jamini Roy, Quamrul Hassan, Qayyum Chowdhury and Rashid Chowdhury. My teacher in India, K G Subramaniam also painted in this flat surface style. I chose folk art for my work by an incident in my life. "My painting won a prize in Japan in 1991 when I was dealing with the problems of the third world countries. I had used four entries with motifs taken from the 'shital pati', and out of 22,000 five countries won the prizes.. I was basically influenced by the Bengal School of Art but I did not use any religious overtures. I've tried to present my human figures and the accompanying motifs of birds, fish, animals and flowers in the simplest possible way. There are six canvases and 34 drawings and paintings on paper.

Abdus Shakoor has had ten solo exhibits and has participated in over 25 international and national exhibitions in India, Italy, France, Russia, UK, Japan, Denmark, Czech Republic, Brazil and Bangladesh. He has won nine awards including the Best Prize at the Lalitkala Academy, Gujrat, India in 1977. He is the head of the department of the Crafts, Institute of Fine Arts, DU. Daily Star, . June 24, 2003 .Abdus Shakoor Saying it with colour

‘This is when I was rethinking about my style and started using folk motifs in my paintings. For me it was the optimum way to present my country through my work. By using original, ethnic symbols, motifs and the language in my paintings, I thought I would be able to contribute in the art movement of our country. It was the beginning of a new era in my career.

I visited several museums to study folk motifs, folk paintings and artefacts of Bengal. I went to the Guru Saday Datta Museum in Kolkata and was very impressed by the huge traditional collection. I realised that with such a treasure of rich ethnic resources in Bengal, why would I choose to go for abstract painting.’ ‘I was highly influenced by Gazir pat, Laxmi sara, alpana, shital pati, nakshi kantha, wood works, wall paintings and other folk art forms. I found the spirit of Bengali nationality in them apart from getting a guideline from them. The works of Jamini Roy had also influenced me in the beginning of my career. But I have developed my own style, adapting it from our folk art. I want to present Bangladesh, the Bengali nationalism, culture and language as my subjects; on the other hand I want to also portray our Asian identity.’

‘I started with random folk motifs in my paintings but later I found my sanctuary in the Maimensingha Gitika, a compilation of folk tales. I paint characters and excerpts of the text from the ballads. A distinct change came into my works. It was 1996 when I began that particular technique and I have not detoured from it since then. In 2000, a curator of a museum in London came to Bangladesh and visited various galleries here, and saw the artworks of different painters. He had heard about my style and came to my house to see my works. He told me that he had finally found the thing he was looking for. He also told me that he could see my country in my paintings. I was pleasantly surprised listening to a professional critic admiring my work.’

He bought fifty of my paintings for the museum and had an exhibition in London. He thought that the best way to present Bangladesh to the people of Britain would be with these paintings.’ At fifty, Shakoor tries to paint every morning and evening. ‘I want to draw new folk motifs with perfection in my canvas. As an artist sometimes I feel like painting spontaneously or whatever comes in my mind. I repeatedly read the books and look for new subjects; if I do, I sketch it first. Sometimes I get only two words, which are enough to build an attractive image for the canvas.’

Besides, Maimensingha Gitika, he also worked on Poet Jasimuddin’s two long poems Sojan Badiyar Ghat and Nakshi Kanthar Math using folk images to mark the birth centenary of the poet. Former director of the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy, Subir Chowdhury, had requested Shakoor to work on the poet. ‘I found many similarities between the images of the Maimensingha Gitika and Jasimuddin’s poems. I drew the faces of Rupai, Saju, Suja and others. I also painted some images symbolically. In 2004 they arranged an exhibition with those paintings.’

‘Young upcoming painters should think about taking up this art form and portray all the tales of the Maimensingha Gitika. As I have been getting older I have limited myself to the characters of Mahua, Malua, Chandrabati, Kajolrekha and Rupabati for my canvas. I like working on those particular characters of the book.’ A suicide scene had impressed the artist immensely. In the book Mahua had taken a knife to kill Nader Chand. Shakoor painted the pale face of Mahua and the back of Nader Chand. ‘Here I used the images of the ballad symbolically.’

Art critics term Shakoor’s works as ‘ethnic’ or ‘regional’. But they also say that his paintings are distinguished with their own characters, which represent Bengal, characters like snakes, peacocks, elephants, birds, flowers and other objects. ‘I have taken these images from the shital pati and nakshi kantha. I also use them as symbols; birds sometimes are symbols of peace, sometimes symbols of sadness and grief. In a shital pati or in a nakshi kantha it is not necessary to identify the type of a bird but the image of a bird is important.’ According to him, when he takes the folk forms he follows the traditional style of their simplicity but when he implements them on his canvas he uses a modern technique. ‘I take the image of a peacock from the shital pati, but I present it in my own style.’

Shakoor uses phrases and sentences from the scripts of the ballads for his paintings. Art critics and the artist himself, thinks that this use of verses enriches his paintings. ‘I choose only human figures, birds and animals; but not images of the rural landscapes. I am just studying the ballads for my new compositions. I have plans to present only the ballads as my subjects of my paintings. It may be considered as the Bangla calligraphy.’

‘I suggest young painters, who are interested in folk art, should study the literature as well as the art. They should not imitate anyone else. They can develop a style of their own. I did not blindly follow Gazir pat; neither the figures nor the images. I have borrowed the style of the scroll, the format and sometimes the division of the panels; but I have used the folk motifs in a modern way’ About the use of colour, he said, ‘I use the colours like children do. My canvas is full of bright colours. I sometimes use earthy or matured colours as per demand. My paintings have a simple look. Not that I like all my paintings, but as a painter, I have to go on.’

The artist usually uses four mediums, ink-drawing, opaque-watercolour, acrylic and oil. Among them he mostly uses ‘opaque-watercolour’ and acrylic. He has also used gouache in a series of his paintings. Although the artist tries to sometime avoid folk motifs, he says, ‘But now, the Bangla folk image is my main stream of painting. I depict and describe the males and females, the ornaments they use or the clothes they wear in the ballads.’ ‘I consciously use a flat surface. I create distance or create perspective. Many of our painters use foreign concepts on their canvases. Abedin Sir (Shilpachariya Zainul Abedin) always discouraged us about that. He used to tell us that we could paint an abstract image but should have your originality documented, so that viewers could identify our works.’ Some artists think that as the language of painting is international they should not be confined to local subjects. Shakoor says, ‘They should keep in mind that all famous artists had established their own individuality in their works. They achieved their individuality by using original, local forms and motifs.’

‘Yes, I do agree that painting has an international ‘language’ but we have seen that the Indian artists have struggled for the last fifty years to establish the fact that painting has also a local ‘language’. It is an irony that artists, who are unable or unwilling to portray their own identity, are looking for global recognition.’ About the repetition of a form, the artist said, ‘If I want to portray the image of Mahua several times, I cannot change the shape of her face. But the expressions of her face will be different in every canvas. Mahua can come again and again in different moods.’

Abdus Shakoor is a teacher at the Institute of Fine Art of the Dhaka University. Commenting on the development of art in Bangladesh, he said, ‘For a small country, the standard can be compared with some major neighbouring countries, including the eastern part of India. If we continue at this pace we will be able to achieve much more in the near future.’ ‘We should be honest with our work. Some of the young painters are doing well. With proper support from the government level they can surely do better in their works. The galleries should take care to give them the money from the sale of their paintings as soon as possible; the artists will be further encouraged. There should be better understanding between the artists and gallery owners, for further development of the art scene in our country.’(New Age, June 2005).1. Album:The Birth Centennial of Poet Jasim Uddin The Painted Verse

2. Jasim Uddin (1904-1976) poet and litterateur

3.The Birth Centennial of Poet Jasim Uddin The Painted Verse

4. Bengali Language

5. The History of Ancient Bengal

5. Romantic Archives: Literature and the Politics of Identity in Bengal

by Dipesh Chakrabarty

( Kimpton Distinguished Service Professor of History and South Asian Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago. His latest book is Habitations of Modernity: Essays in the Wake of Subaltern Studies (Chicago, 2002).)The long Bengali nineteenth century is perhaps finally dying. It may therefore make sense to treat its death as a proper object of historical study. In the context of the remarks made by my friend whose sentiments made me think of the subject of this essay, I want to ask: What was the nature of the bhadralok investment in literature and language that once made these into the means of feeling one's Bengaliness? Here it is useful to pay some attention to the works of Dinesh Chandra Sen, the pioneering historian and a lifelong devotee of Bengali literature.4 Once hailed as the foremost historian of Bengali literature, he was lampooned by a younger generation of intellectuals in the 1930s who faulted his sense of both politics and history. It is the story of the early reception and the later rejection of Sen's work that I want to use here as a way to think about the questions raised by my friend.

A few biographical details are in order. Born in a village in the district of Dhaka in 1866, Dinesh Chandra Sen (or Dinesh Sen for short) graduated from the University of Calcutta with honors in English literature in 1889 and was appointed the headmaster of Comilla Victoria School in 1891 in Comilla in Bangladesh. While working there, he started scouring parts of the countryside in Eastern Bengal in search of old Bengali manuscripts. The research and publications resulting from his efforts led to his connections with Ashutosh Mukherjee, the famed educator of Bengal and twice the vice chancellor of the University of Calcutta (1906–1914 and 1921–23). In 1909, Mukherjee appointed Sen to a readership and subsequently to a research fellowship in Bengali at the university. 5. Sen was eventually chosen to head up the postgraduate department of Bengali at the University of Calcutta when that department—perhaps the first such department devoted to postgraduate teaching of a modern Indian language—was founded in 1919. Sen served in this position until 1932. He died in Calcutta in 1939. Sen produced two very large books on the history of Bengali literature: Bangabhasha o shahitya (Bengali Language and Literature) in Bengali, first published in 1896, and History of Bengali Language and Literature (in English), based on a series of lectures delivered at the University of Calcutta and published in 1911. 6. He also produced many other books including an autobiography. All his life, Sen remained a devoted, tireless researcher of Bengali language and literature. 7.

Sen, today, is truly a man of the past. His almost exclusive identification of Bengali literature with the Hindu heritage, his idealization of many patriarchal and Brahmanical precepts, and his search for a pure Bengali essence bereft of all foreign influence will today arouse the legitimate ire of contemporary critics. It is not my purpose to discuss Sen as a person. But, for the sake of the record, it should be noted that, like many other intellectuals of his time, Sen was a complex and contradictory human being. This ardently and (by his own admission) provincial Bengali man loved many English poets and kept a day's fast to express his grief on hearing about the death of Tennyson. 8. For all his commitment to his own Hindu-Bengali identity, he remained a foremost patron of the Muslim-Bengali poet Jasim Uddin. 9. The inclusion of a poem by Jasim Uddin in the selection of texts for the matriculation examination in Bengali in 1929, when Hindu-Muslim relations were heading for a new low in Bengal, was directly due to Sen's intervention at the appropriate levels. 10. And his patriarchal sense of the extended family did not stop him from encouraging his daughters-in-law to pursue higher studies. 11.

6. For a factual revision of Dinesh Sen’s research findings see the appendices added by Prabodh Chandra Bagchi and Asitkumar Bandyopadhyay to Dinesh Chandra Sen, Bangabhasha o shahitya, ed. Asitkumar Bandyopadhyay, 2 vols. (Calcutta, 1991), 2:868–89.

7. Biographical details on Dinesh Sen are culled here from his autobiography, Gharer katha o jugashahitya (1922; Calcutta, 1969; Supriya Sen, Dineshchandra; biographical note entitled "The Author's Biography" published in Dinesh Chandra Sen, Bangabhasha o shahitya, 1:43–5; and "The Author's Life," in Dinesh Chandra Sen, Banglar puronari (Calcutta, 1939), pp. 1–32. A later reprint of this book (1983) says in a publisher’s note that this short biography given in the first edition contains some factual errors. But the facts stated here seem to stand corroborated by other sources.

8. Supriya Sen, Dineshchandra, p. 19.

9. Sen’s relationship to Jasim Uddin is the subject of the latter’s reminiscence in Smaraner sharani bahi (Calcutta, 1976). Jasim Uddin writes:

Here was a man who took me from one station in life to another. My student life perhaps would have ended with the I.A. [Intermediate of Arts] degree if I had not met him. Perhaps I would have spent my life as an ill-paid teacher in some village school. I think of this not just only once. I think this every day and every night and repeatedly offer my pronam [obeisance] to this great man. [P. 71]Wahidul Alam writes:

I was surprised when in 1929 I read Jasim Uddin's poem "Kabar" in Calcutta University’s selection of Bengali texts for the Matriculation examination. A poem by a Muslim writer in the Matriculation selections! And that too under the auspices of the University of Calcutta? . . . A teacher of mine told me a story about this. There was forceful opposition in [the University's] Syndicate to the inclusion of by a student. But Dr Dinesh Sen was the number one advocate for Jasim Uddin. . . . Apparently, he countered the opposition by saying, "All right, please be patient and just listen to me recite the poem." He had a passionate voice and could recite poetry well. He read the poem with such wonderful effect that the eyes of many members of the Syndicate were glistening with tears. Palli-kobi Jasimuddin Festival -"Nakshi Kanthar Math

The narratives of the rustic Bengal and its people have always been presented artistically in Palli-kobi Jasimuddin's poetry, touching the soul of readers. To pay homage to the poet, Department of Production of Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy (BSA) has arranged a three-day programme at the National Theatre Stage. Secretary of the academy, Ashraful Musaddeq inaugurated the programme on June 3. Media personality Muhammad Jahangir, also the coordinator of dance troupe Nrityanchal, was the special guest. Director, Department of Production, Zinnat Barkatullah delivered the welcome speech.

Muhammad Jahangir said, "Besides academic curriculum at school and college levels, Jasimuddin's works do not get the exposure they deserve. While most of the 20th century Bengali poets are highly influenced by Rabindranath Tagore, Jasimuddin is one of the few who have developed their distinct styles. I believe that by labelling the poet 'Palli-kobi', the urban literature enthusiasts have 'subconsciously' sidelined his creativity. I appreciate the current endeavour of the academy and expect more such elaborate programmes in future." Ashraful Mosaddeq said, "If a poet doesn't offer any new 'form' or 'idea', he/she can never survive the test of time. Jasimuddin is successful in presenting our rural culture in a modern light. To promote his work we will take more initiatives."

After the discussion, Nrityanchal staged a dance-drama titled Nakshi Kanthar Math, based on Jasimuddin's popular narrative poem with the same title. Under the guidance of Zinnat Barkatullah, the troupe revived the show, which was premiered in 1981. Zinnat Barkatullah informed, "In 1981, BSA sent Nakshi Kanthar Math to Italy. Shibly Mohammed, Shamim Ara Nipa and I were the lead performers in the dance-drama. The poem is dramatised by Golam Mujtaba and the dance-drama is directed by Mostafa Manowar. Veteran dancer GA Mannan is the choreographer and Ustad Khadem Hossain Khan is the music composer. Indramohan Rajbongshi and Nina Hamid render the playback for the tunes. Tonight's show maintains the same presentation style of the premier performance." Featuring the tragic love story between Shaju and Rupai, portrayal of rural Bangladesh -- traditions, struggles and way of living as a whole -- is presented eloquently in Nakshi Kanthar Math.

The dance-drama begins with a drought scene. The villagers arrange a socio-religious ritual praying for rain. At the event Rupai (Shibly Mohammed) meets Shaju (Shamim Ara Nipa); it's a classic case of love at first sight. The lovers get married but the bliss does not last long. Tragedy occurs when thugs come to loot the crops of the villagers, resulting in a conflict. Five die and Rupai is wrongly accused. To evade the situation, he sees no other way but to flee.

Rural customs and festivities like harvest, fishing and wedding, have been emphasised, rather than focusing on just the love-story. The dramatisation of solitude by Shibly and Nipa deserve a special mention. Nipa embodied the melancholy of the character Shaju, who pines away for her beloved and succumbs to death. The story ends with Shibly as Rupai, delivering a remarkable performance when the character returns home and finds a nakshi kantha (embroidered quilt), in which Shaju had delineated moments from her lonesome life (Daily Star, June 5, 2007).Dance-drama "Kabor" staged at Jasimuddin Festival

Four dance recitals and the dance-drama Kabor were staged on the second day (June 4) of the ongoing three-day 'Jasimuddin Festival' at the National Theatre Stage. The Department of Production of Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy has arranged the festival. Choreographed by Kabirul Islam Ratan, dance troupe Nrityalok Sanskritik Kendra presented three recitals based on Palli-kobi Jsimuddin's evergreen verses. Young dancers of the troupe presented the first composition based on Tumi jabey bhai, jabe mor shathey amader chhoto ganye, rendered by Kiron Chandra Roy. The troupe also staged two recitals based on Amaye bhashaili re amaye dubaili re and Allah megh de pani de.

Tonatuni staged a dance drama Kabor adapted from the popular poem Kabor by Pallikobi Jasimuddin.

The dance drama starts with the effect of the dawn when the last lines of the Fazr Azan is heard. A very old grandfather comes on stage in feeble steps and starts telling his story to his grandson. The unhappy grandfather tells him about the five deaths in his family. He also recollects the memories of his getting married, the little bride's doll playing, the fair they attended, the bride's bathing with her friends and other insignificant yet happy moments of his life.

Directed by dancer Dipa Khondokar with light directions by famous light director of Kolkata Tapash Sen, the total performance was excellent. Earlier in the programme Tapash Sen, who is known as 'The Magician of Lights', was awarded a medal by the chief guest Minister for Cultural Affairs Selima Rahman. A CD of Jasimuddin's Nimantran, sung by Kiron Chandra Roy, was also launched by the wife of Pallikobi, Begum Mamataz Jasimuddin. To the delight of the audience, Kiron Chandra Roy sang the title song of the CD Nimantran.

Young artistes -- Labonya and Robin -- of dance troupe Shupto Bikash, presented a composition based on Rakhal chhele rakhal chhele barek phirey chao by Jasimuddin. Shafiqur Rahman is the choreographer of the piece. The major attraction of the evening was the dance-drama Kabor based on Jasimuddin's poignant elegy with the same title. Through the 'dramatic monologue' of a grandfather -- looking over his wife's grave -- the tragic experiences of losing near and dear ones are narrated to a grandson. But, the sole intention is not to narrate the stories of 'death'. The elderly character also narrates his passion for the loved ones. And these cherished memories as well as his feelings at the parting of the family members have been presented in flash back scenes.

Director Deepa Khondokar's efforts deserve plaudits, specifically the presentation of rural Bangladesh. The "village fair" scene is vibrant. Set designer Kiriti Ranjan Biswas and noted Indian light designer Tapash Sen creates a realistic ambience. Music for the dance-drama has been composed by Shujeo Shyam. Actor-director-recitor Mujibur Rahman Dilu has done the recitation. Before the show, Mujibur Rahman, also the co-coordinator of the production Kabor, spoke at the programme. The dance-drama is a Tonatuni production (Daily Star, June 6, 2007).Jasimuddin Festival- Songs

The three-day 'Jasimuddin Festival' organised by the Department of Production, Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy, ended on June 5 at the National Theatre Stage. To pay homage to the Palli-kobi, his works were presented through music, dance-drama and recitals. On the last day of the festival, evergreen songs written by Jasimuddin were rendered by 21 leading folk singers of the country. Folk songs belonging to genres like Moromi, Bichhedi, Bhatiali and Shari were performed at the programme. Jasimuddin is widely known for his poems such as Nakshi Kanthar Math, Shojon Badiyar Ghat, Kabor and many more, in which he captured the essence of rural Bengal and the unpretentious lives of peasants. However, most urbanites are not acquainted with his skills as a lyricist and composer. Perhaps many are not aware that familiar folk songs including Amar har kala korlam re, Amaye bhashaili re, Bondhu rongila re, Nishithey jaiyyo phulo bon-e, Nodir kul nai kinar nai re and O amar dorodi were written by the poet.

Most of the songs by Jasimuddin belong to Moromi (devotional) genre. These songs can be interpreted in more than one way; an unmistakable trait of mystic songs. References to relatable characters and elements like "friend", "boatman" and "river", the poet articulated his love for God. The programme began with the rendition of a Bichchhedi (melancholy) song Tumi kaindo na orey amar jabar bela by Sardar M Rahmatullah. Meena Barua sang Ujan ganger naiyya. Kiron Chandra Roy presented Tumi jabey bhai -- a fusion of folk and classical music. An emotionally charged Deepti Rajbongshi's rendition of the devotional song Swarup tui biney dukkho bolbo kar kachhe moved the audience. Stentorian vocals of Malay Kumar Ganguli, Bipul Bhattacharjee, Abu Bakar Siddiqui and Khogendranath Sarkar during presentations of songs -- O amar dorodi, Amaye bhashaili re, Jarey chhere elam obohele and Ami baiyya baiyya kon ghatey respectively were also enjoyable (Daily Star, June 7, 2007)

6. Bengali Folklore and Children's Literature

Barnita Bagchi, INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.21 APRIL 2006 BARNITA BAGCHI, Institute of Development Studies Kolkata (IDSK), Calcutta University Alipur Campus, E-mail: barnita@gmail.com, barnita@idsk.org

Jasim Uddin (1903-1976), who became one of the iconic poets of liberated East Pakistan, namely Bangladesh, was also heavily influenced by Dineshchandra Sen, under whom he worked as Ramtanu Lahiri Assistant Research Fellow from 1931 to 1937, collecting folk literature. His very first book of verse, Rakhali (shepherd) (1927) offered evidence of his passionate love and commitment to rural Bengal as a utopian and lyrical locus. Some of his most famous works were Naksi Kanthar Math (The Field of the Embroidered Quilt) (1929) and Bangalir Hasir Galpa INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.21 APRIL 2006 (Humorous Tales of Bengalis). Again, Jasim Uddin's deep involvement in non-communal socio-political movements championing the cause of Bengali language and literature gives his lyric and folksy poetry a keen edge of commitment and protest. His poems are popular as part of school curricula in West Bengal, India as much as in Bangladesh. Satyajit Ray records in his autobiography that he was taught in school by Jasim Uddin.

In 1968, Ray directed a film which is to date one of the most loved works , among children and adults alike: Goopy Byne Bagha Byne (The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha). The folk-tale like story on which the film is based was written by Ray's grandfather Upendrakishore Roy Chowdhury (1863-1915), a man of numerous talents like his son Sukumar Ray and his grandson Satyajit. It was Upendrakishore who started the legendary children's magazine Sandesh, which was revived by Satyajit and his cousins, and which is still published.

Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne is the story of two simple village lads, who speak a distinctive East Bengal dialect. In Ray's hands, the earthiness, good nature, and simplicity of the lower-caste Goopy, the singer, and Bagha, the drummer, assume a particularly potent positive force when contrasted with the exploitative, parasitic, rapacious malice of the upper caste village elders Goopy is banished by. A bad singer and a bad drummer, Goopy and Bagha are blessed by a marvellously eerie King of Ghosts, who give them three boons whereby they can eat what they want, go where they want, and please people with their music. On their adventures, Goopy and Bagha go off to a country misruled by a wicked, imperialistic, warmongering minister-again, Ray's social commentary, in the context of the anti-US imperialist movement of the late 1960s is obvious. Alongside, Ray created charming, lilting songs that are still on the lips of most Bengalis.

How does the strange bird

flit in and out of the cage,

If I could catch the bird

I would put it under the fetters of my heart

....................................................................

O my mind, you are enamoured of the cage;

little knowing that the cage is made of raw bamboo,

and may any day fall apart

Say Lalon, forcing the cage open

the bird flitted away, no one knows where (Lalon Song).

.

The village birds return home after playing

on the sand bank.

The birds on the sand bank are continuously crying. ( Jasim Uddin)Tuntuna and Tuntuni

There were once two tailor birds called Tuntuna and Tuntuni.... One day Tuntuna said to his wife. "My dear Tuntuni, I wish I had some money...." After many days of searching, he found a pence under a bush. He took it in his beak and carried it to Tuntuni.....

"Tuntuni, we have become rich!".....

They were so happy that they forgot about eating and sleeping. They just danced and singing:

"How much money does the king have?

That's how much money we have"

....When the king heard the words of the birds and made him very angry and ordered to catch them immediately.....

The commander of Chief at last with the help of the fishermen caught the birds.

The king gave the birds to his 101 queens...The birds were passed from one queen to another. The lazy queen did not hold the bird tightly, and first Tuntuna then Tuntuni flew out of her hands.....No one of the queens dared to tell the king what had happened.

... The next day, the king call all the wise men in the land to his court to judge the Tuntunis...

The king ordered the birds to be brought into the court. He waited and waited, but the Tuntunis did not come....

Suddenly, the Tuntunis came flying over the king's head.. and singing:

"Tuntuna, Tuntunni,

Tuntunis tun tun!

All the queens noses

Are as red as roses!

Tun tun, tun tun, tun tun."

The king could control his anger. "Catch those Tuntuni bird," he shouted....

Soon the two birds were caught in the nets, but this time the king would not wait for his wise men to judge them. He took a glass and swallowed tuntuna and tuntuni.

The wise men shook their heads. One of them said to the king's first minister, "The first time the king laughs the Tuntuni birds will fly out of his mouth."

So the first minister ordered a soldier to stand on each side of the king. He said, "When the king laughs, the birds will fly out of his mouth .. You must cut off their heads with your sword as soon as you see them."

Just then one of the queens came to talk to the king. She was the queen who was always laughing. When the king turned to speak to her, the queen began to laugh. Of course, the king has to laughs too.

As soon as the king started laughing the Tuntunis flew out of his mouth. "Zing Zing," went the soldiers swords, but they did not catch the birds. Instead of chopping off the heads of the Tuntunis, the soldier had chopped off the nose of the king. Tuntuna and tuntuni flew round and round the room, singing:

"Tuntuna, Tuntuni

Tuntunis tun tun!

The nose of the king,

Was cut "Zing zing zing"!

Tun tun, tun tun, tun tun."

(From The Folk Tales of Bangladesh by Jasim Uddin)

7. Nandikar plans to recreate Jasimuddin’s world on stage

YOU enter the auditorium hoping to experience yet another typical Bengali production and suddenly find yourself on the windswept sandflats of a distant river.

The roof of the auditorium vanishes, giving way to an open sky, albeit simulated. Welcome to the long overdue new production from Nandikar’s stable, Sojan Badiar Ghat, at the Academy of Fine Arts on March 26.

There are other surprises in store, too. For example, a stage that extends into the auditorium through two bridge-like ramps. “We had worked upon every element meticulously. I promise an absolutely new feel to the audience as soon as they walk in,” said Gautam Haldar, who is at present busy giving the final touches to what he regards as one of his most challenging directorial assignments. After all, directing a stage adaptation of the work of one of opar Bangla’s most elemental poet -- Jasimuddin-- is no easy task.

“I wanted to do something like the Westside Story, but I couldn’t get a Bengali counterpart. Then, five years back, while working on Jasimuddin’s Nakshi Kathar Matth, I suddenly chanced upon Sojan...,” he said. And from then on, this poetry has haunted him and his friends in Nandikar— Debshankar, Partha and others. Nandikar’s driving force, Rudraprasad Sengupta, is also excited about the project. “Not only is it Jasimuddin’s centenary this year; I believe this production which delves into the essential humane elements in a riot-ravaged village community, is pertinent in our times.”

The cast is huge — 50 protagonists — something Sengupta claims has not happened in recent Bengali stage history. Sengupta is also happy that the next generation has finally taken up the responsibility of a Nandikar production. And they are planning a ‘festival’ exclusively for Sojan...sometime in April. This sure promises to be a grand affair (Times of India, 14 March, 2003).Sojan Badiyar Ghat Gypsy Wharf (also in Italien: Zingaro Sugiom)

Nandikar’s latest production is based on Jasimuddin’s verse epic, Sojan Badiyar Ghat. One of the renowned poets of Bengal, Jasimuddin’s folk tales are based on strife, war, love and death that tear apart the two communities, Hindus and Muslims. Sojon, a Muslim youth, falls in love with his childhood friend, Duli, a Hindu girl. Their affair sparks off tension between the two communities, and the duo elope. But in no time, Sojon is traced and imprisoned. Duli is married off to a Hindu zamindar. But as fate has pre-ordained, their paths cross once again and they meet, but this time to give up their lives together for love. This simple and eternal tale of love is intricately woven with the larger reality of communal hatred and the petty political manipulations that go along with it. It is this aspect of the play that makes it meaningful and contemporary. The form of the play is painted on a diverse and ethnic canvas. Folk music and diverse rural activities, including laathi khela, have been extensively used in this production. Bamboo and traditional hand-painted patas contribute to the stage decor. The play has been directed and set to music by Goutam Halder (The Daily Telegraph, Calcutta, India,March 26, 2003).

Abiding tale of love & revolt

SUBHORANJAN DASGUPTA

Pallikabi (village bard) Jasimuddin was born on the first day of 1903, and his birth centenary is being observed this year. But is he merely a village bard or, like Robert Burns, a remarkable poet who challenged the rural-urban and rustic-refined divide?

When one reads his lyrics, like Gourigirir meye (a sensitive yet heartfelt invocation to Goddess Durga) and Anurodh (a chiselled love poem woven in folk rhythm) and then goes on to respond to his two evergreen dramatic poems Naksi-kanthar Math and Sojonbadiar Ghat, one concludes that the label ‘village-bard’ is an example of inadequate salutation.

Both these ballads cross the prescribed limits of folk poetry. In fact, they articulate a secular and humanist vision in a diction that is earth-sprung and elegant. No wonder, both these ‘modern’ ballads, replete with social conflicts, have been dramatised. While Naksi-kanthar Math was given a vibrant, dramatic form by Kalyani Natya Charcha Kendra in 2001, Nandikar’s latest venture has transformed Sojonbadiar Ghat into a collective spectacle. The guiding spirit behind both these splendid productions is Gautam Halder, who has proved with his friends that Jasimuddin can inspire exciting theatre. Perhaps, ‘theatre’ is not the apposite descriptive. For, Nandikar’s centenary homage to the poet integrates the musical, dance-theatre and dialogue-based drama into one indivisible format.

The closely-entwined personal and social layers, both equally intense in this dramatisation, convey the abiding message of love and revolt.

While the Muslim village lad Sojon and his heartthrob Duli, a Nomosudra belle, trample barriers to come together, their village, Simultali, experiences bloody clashes between the two communities, engineered by the high-caste Hindu nayeb of the local landlord. Ultimately, the star-crossed lovers choose death and their last act of defiance perpetuates the message of deathless harmony. In all, 21 musical instruments, 40 singers and 51 actors merge and clash, coalesce and collide on the stage to embody the poet’s ideal. Jasimuddin’s flowing verse leaps and sparkles as the actors and singers turn his words into war cries and laments.

Jasimuddin, who loved to infuse the lyric with the dramatic, would have loved two particular scenes. In the first, Duli lovingly explains the Hindu and Muslim themes of her paintings to Sojon, in an atmosphere of conjugal warmth.

In the second, this syncretic ambience is shattered by the outbreak of sectarian vendetta. Incited by the crafty nayeb, fierce Nomosudras confront vengeful Muslims and their furious dance exposes the futility of it all. A fine excess of songs recreating the world of baul-bhatiyali-ajan-kirtan weaves the protesting, choric design.

We recall Sojon and Duli with a sense of special urgency in our divisive times. They impart the mantra of love and tolerance in world vitiated by the Talibans and Togadias. Finicky post-moderns might find the ‘secular’ storyline grossly simplistic, even Utopian. But neither Jasimuddin nor Nandikar, anchored to the soil, have whitewashed the vitriol and violence ingrained in us. We confront their awesome might but then aspire for the resplendent Utopia from the sphere of our soiled lives. (The Telegraph, Calcutta, India, Thursday, May 15, 2003 )The Telegraph - Calcutta : At Leisure CIMA Gallery The Telegraph ...Gautam Halder ’ s concept , dramatisation and direction of Jasimuddin ’ s poetic work ... Jasimuddin ( 1903 - 76 ) was a pioneering folk revivalist poet

New box-office formula, THEATRE , ANANDA LAL

Going by sheer popularity, the current blockbuster that repudiates the supergroup idea as the only way to draw audiences comes from that tightly-knit and -run unit, Nandikar. For Sojan Badiyar Ghat, you must book your seat days in advance. I am not equating full houses with aesthetic achievement, but Nandikar evidently has given the lie to Bengali groups’ complaints that nobody watches theatre any more.

Part of the magic is the style that Nandikar has developed over the last few years: a vibrant, full-blooded, large-cast, scenographically spectacular, song-and-dance extravaganza, a feast for the eyes and ears. Plus, they go about it with such professionalism and precision choreography that one can only marvel at the discipline and intensive labour underlying what we see on stage. Gautam Halder’s concept, dramatisation and direction of Jasimuddin’s poetic work continue this pattern.

Jasimuddin (1903-76) was a pioneering folk revivalist poet, who settled in East Pakistan after 1947. His verse has a simple, charming rural authenticity that gives it a near-pastoral feel, and many critics consider Sojan Badiyar Ghat as its acme. It tells of the love between a Muslim boy and Hindu girl, who elope, but he is jailed and she married off to a rich zamindar. After his release, the story moves to a Romeo-and-Juliet-like conclusion. Without polemics, it pleads strongly for communal amity.

Halder himself and Sohini Sengupta Halder portray the romantic leads vivaciously, and convey Jasimuddin’s favourite theme of doomed love sympathetically. Both sing (Halder also composed the music) and the huge cast contributes to the colourful ensemble. Sanchayan Ghosh yet again designs impressive sets with bamboo ghats jutting into both flanks of the auditorium. This is not the first time Halder has attempted Jasimuddin; he applied similar treatment to Nakshikanthar Math for Kalyani Natyacharcha Kendra in 2000. It would be interesting if he shifted from Jasimuddin’s poems to his lyrical plays Beder Meye or Pallibadhu for a change, but using a different theatrical approach.Nandikar, a Kolkata-based theatre group, was part of the on-going Ranga Shankara theatre festival.

VIJJAY NAIR

Nandikar, a 40-year-old theatre group from Kolkata, has visited Bangalore a number of times in recent years. They were back recently with three productions, two of which were performed for the ongoing national theatre festival at Rangashankara.

The first play, staged by the group on November 5, was at Ambedkar Bhavan for the Bengali Association. A musical based on poet Jasimuddin’s Sojon Badiyar Ghat was remarkable for the manner it was conceptualised as well as executed.