|

|

Grameen bank

|

If you take a flower

You have to give

A

heart like flower.

Give flowers in return

They give

false flowers.

.....................

How will you

carry such a flower?

A flower cannot carry another

flower.

Jasim

Uddin

|

|

1. INTRODUCTION

2. Conventional bank do not lend to the

poor

3. Credit for the ultra-poor

4. Extension and Interaction with Officials

5. Improvements in Well-Being

6. Household Decision-Making

7. Samman/Dignity

8. The Market

9. Savings

10. Village phone programme

11. Pension fund and other savings

12. Self-reliance for GB

13. High Cost of Microcredit

14. The Struggle for Survival and Credibility among the

Religious NGOs (Non-Governmental

Organizations) in Bangladesh

15. CONCLUSION

16. REFERENCES

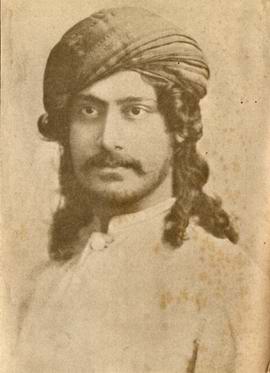

Grameen's Success - Rabinranath Tagore knew 100 years

ago

The success of Grameen project

is entirely due to the responsiblity and participatation by

the women. Rabinranath Tagore knew this. The success of Grameen project

is entirely due to the responsiblity and participatation by

the women. Rabinranath Tagore knew this.

In traditional rural society women's place considered to be

high and respectful., as woman is made mother by Nature.

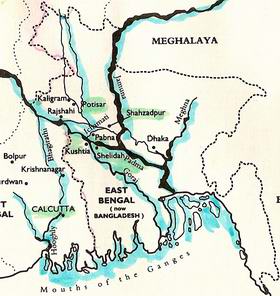

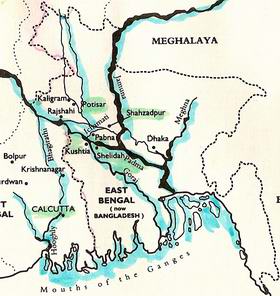

Rabinranath Tagore, the Noble Prize laureate, wrote on 18th

August 1893, Potisar (Padma, downstream of the Ganges),

also Rabinranath Tagore named the boat "Padma",

Bangladesh:

For some time I have been remarking that man

is angular and incoherent, women rounded and

complete. Woman's way of speaking, dressing, moving and

behaving is an integral harmony with her duties in life. And

the main reason is that for ages Nature has defined these

duties and modified these duties and moulded her feelings to

fit to them. . In all her being and doing she unites grace

and skill, her nature and her work, like a flower and its

scent. She acts without conflict or hesitation."

Man's character, by contrast, is uneven, formed by

the various occupations and influences that have left their

mark upon him both inwardly and ouwardly.

......

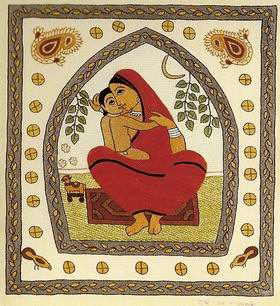

Woman was made mother by Nature and cast in

that mould. but man has no such primal design, no star

perpetually to gude him

(Rabinranath

Tagore, Glimpses of Bangal, His letters to his niece Indira

Devi)

|

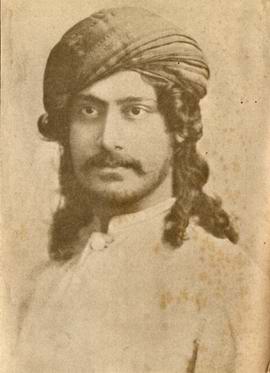

Rabindranath Tagore – The Poet And The Man An Analytical

Perspective

Glimpses of Bengal

1. INTRODUCTION

In Bangladesh, the unintended

consequences of the microcredit system with NGOs as partners have

been far-reaching. The very structure of social production that

focused on 'man as the breadwinner' has changed to accommodate a

substantial and permanent role for women as income-earners. In Bangladesh, the unintended

consequences of the microcredit system with NGOs as partners have

been far-reaching. The very structure of social production that

focused on 'man as the breadwinner' has changed to accommodate a

substantial and permanent role for women as income-earners.

'The Grameen Bank' project, an invention of a simple method by a

man from the world's poorest country has become a model for so many

developed and developing countries of Asia, Europe, America and

Africa for changing the fate of their underprivileged people. First

Tagore, then Amartya Sen and finally our very own Dr. Yunus. This is

the type of news that can make a Bangladeshi proud.

The IFAD-government of Bangladesh, Agricultural Development and

Intensification Project (ADIP) covers four districts: Gazipur,

Tangail, Kishoreganj and Narsinghdi. This study of 20 saving and

credit groups (SCGs) formed under the ADIP project in these four

districts of Bangladesh was undertaken to assess the impact of

microcredit institutions on gender relations and women’s agency.

During our fieldwork (from March 17 to 31, 2003), we looked at the

process through which microcredit has enabled the transformation of

a part of women’s domestic labour into an income generating

activity. We looked at the sectors of economic activity in which

this credit is invested and the productive assets acquired by the

members of the SCGs.

Grameen Bank was initiated in 1976 by

Professor Muhammad Yunus as an action research project of Chittagong

University. In a village near the university called Jobra, he found

that the poor did not have access to small amounts of capital to

engage or build on their tiny livelihood activities. The only source

of capital were loans from money- lenders at exorbitant rates of

interest. As an experiment, he began a project to provide small

loans to poor women in Jobra to engage in income generating

activities. In all cases, the poor women took loans from the

project, invested their money, and generated enough income to pay

back their loans and keep a profit. Grameen Bank was initiated in 1976 by

Professor Muhammad Yunus as an action research project of Chittagong

University. In a village near the university called Jobra, he found

that the poor did not have access to small amounts of capital to

engage or build on their tiny livelihood activities. The only source

of capital were loans from money- lenders at exorbitant rates of

interest. As an experiment, he began a project to provide small

loans to poor women in Jobra to engage in income generating

activities. In all cases, the poor women took loans from the

project, invested their money, and generated enough income to pay

back their loans and keep a profit.

The word "microcredit" did not exist before the seventies. Now it

has become a buzz-word among the development practitioners. In the

process, the word has been imputed to mean everything to everybody.

No one now gets shocked if somebody uses the term "microcredit" to

mean agricultural credit, or rural credit, or cooperative credit, or

consumer credit, credit from the savings and loan associations, or

from credit unions, or from money lenders. When someone claims

microcredit has a thousand year history, or a hundred year history,

nobody finds it as an exciting piece of historical information.

The Grameen Bank operates on the premise that

the poor remain poor, not because they do not work or do not have

skills, but because the institutions created around them keep them

poor. Charity is not a solution to poverty, but rather fosters

dependency, thus perpetuating poverty. All human beings are born

with unlimited potential, and merely require an opportunity to

unleash that potential. Professor Yunus argues that credit provides

that opportunity and should therefore be considered a human

right. The Grameen Bank operates on the premise that

the poor remain poor, not because they do not work or do not have

skills, but because the institutions created around them keep them

poor. Charity is not a solution to poverty, but rather fosters

dependency, thus perpetuating poverty. All human beings are born

with unlimited potential, and merely require an opportunity to

unleash that potential. Professor Yunus argues that credit provides

that opportunity and should therefore be considered a human

right.

The success of this approach shows that a number of objections to

lending to the poor can be overcome if careful supervision and

management are provided. ‘For example, it had earlier been thought

that the poor would not be able to find remunerative occupations. In

fact, Grameen borrowers have successfully done so. It was thought

that the poor would not be able to repay. But in reality, the

repayment rates reached were 97 per cent. It was thought that poor

rural women in particular were not bankable. The numbers say

otherwise, they account for 97 per cent of borrowers today. Indeed,

from fewer than 15,000 borrowers in 1980, the membership had grown

to nearly 100,000 by mid-1984. Group savings have reached 7,853

million taka, out of which 7,300 million taka are saved by women.

Many people mistakenly consider Yunus as the pioneer of micro-credit in Bangladesh. When Rabindranah Tagore established a bank for the peasants at Potisor in Pabna, he did not coined the term micro-credit. The poet-turned-philanthropist made a huge amount of grant to help poor farmers. He failed to recover the loan, not even 20 per cent. We know about Kabuliwala (Afgani)was who generously gave collateral-free loan to anybody. NGOs later institutionalised it. BRAC was the first NGO that advanced collateral-free micro-credit in its Sulla Project on an experimental basis in 1974 as a package for post-flood rehabilitation. It has become a regular programme of BRAC since 1976 with 12 per cent rate of interest per year.

The government in 1983 established the Grameen Bank (GB) as a non-profit organisation to implement a group-based credit programme for productive self-employment, though it started as an action-research project in 1976. However, it was Yunus who preached credit as a right of the poor. He considers credit as a human right. His hypothesis has been: the poor are bankable.

|

Myth of recovery

The micro-credit programme provides easy access to credit for the poor, as it is collateral free. It also extends awareness service, development education and training on various social and vocational aspects to the beneficiaries for effective utilisation of the credit. Efforts are made to make the poor creditworthy. In spite of these efforts, many borrowers default and ultimately drop out.

When the default rate is very high and the repayment rate declines to an alarming level, it threatens the survival of the institution. Performance of some NGOs has been poor and some of them had to abandon the programme. For some NGOs, the default rate was more than 90 per cent. Low repayment rate has its demonstration effect on others, which often spreads a default culture.

Increased amount of credit is sometimes a problem. A survey conducted by ASA shows that competition of NGOs involved in micro-credit programme in the same area often creates an unhealthy situation and influences in creating default. Organisations like BRAC, Grameen Bank and Proshika provide large amounts of credit to their clients. In an environment of poor infrastructure and hostile attitude of the bureaucracy, the poor people do not have the capability to utilise a large amount through investment as capital. When the loan amount is beyond the capacity, they cannot generate desired income.

GB and some national NGOs have been able to keep their recovery rate high. But there is scepticism about their claim. In the backdrop of low rate of return on labour, high degree of uncertainty and natural disasters, a high rate of repayment to the tune of 99-100 per cent on a regular basis seems to be a miracle. What makes such a high rate possible? The following have been observed in this respect.

Many borrowers have access to multiple sources of credit.

Borrowers are assured of repeat loans. Defaulters’ loan is adjusted with fresh loan and shown as ‘recovered’. Staffs are at a race to show their performance.

Borrowers have multiple sources of income.

Borrowers have to sell assets to clear themselves when in trouble.

Borrowers are intimidated to repay loan.

NGOs incur high staff cost to keep vigilance.

Yunus makes nation proud Shares Nobel Peace Prize with his

Grameen Bank

After independence in 1971 and

restoring democracy in ’91, Bangladesh witnessed the biggest

achievement as Professor Muhammad Yunus and his Grameen Bank

were declared yesterday to win the Nobel Peace Prize 2006 for

pioneering the use of micro-credit to benefit poor

entrepreneurs. Prof Yunus is the first Bangladeshi and also

the third Bangalee after poet Rabindranath Tagore and

economist Amartya Sen to win the Nobel Prize. Grameen Bank,

founded by Prof Yunus, has been instrumental by offering loans

to millions of poor Bangladeshis, many of them women, without

any financial security, in improving their standard of living

by starting businesses with the tiny borrowed sums After independence in 1971 and

restoring democracy in ’91, Bangladesh witnessed the biggest

achievement as Professor Muhammad Yunus and his Grameen Bank

were declared yesterday to win the Nobel Peace Prize 2006 for

pioneering the use of micro-credit to benefit poor

entrepreneurs. Prof Yunus is the first Bangladeshi and also

the third Bangalee after poet Rabindranath Tagore and

economist Amartya Sen to win the Nobel Prize. Grameen Bank,

founded by Prof Yunus, has been instrumental by offering loans

to millions of poor Bangladeshis, many of them women, without

any financial security, in improving their standard of living

by starting businesses with the tiny borrowed sums

"Lasting peace cannot be achieved unless large

population groups find ways in which to break out of poverty.

Micro-credit is one such means," said Ole Danbolt Mjøs,

chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee. "Muhammad Yunus has

shown himself to be a leader who has managed to translate

visions into practical action for the benefit of millions of

people, not only in Bangladesh, but also in many other

countries." Prof Yunus and Grameen Bank were chosen for the

prestigious award from among 191 candidates, including 168

individuals and 23 organisations.

Yunus, dubbed "Banker to the

Poor", began fighting poverty during a 1974 famine in

Bangladesh with a loan of $27 out of his pocket to help 42

women buy weaving tools to save them from the clutches of the

moneylenders. "They got the weaving tools quickly, they

started to weave quickly and they repaid him quickly," said

Mjøs. "Yunus and Grameen Bank have shown that even the poorest

of the poor can work to bring about their own development,"

the Nobel Committee said in its citation. Yunus, dubbed "Banker to the

Poor", began fighting poverty during a 1974 famine in

Bangladesh with a loan of $27 out of his pocket to help 42

women buy weaving tools to save them from the clutches of the

moneylenders. "They got the weaving tools quickly, they

started to weave quickly and they repaid him quickly," said

Mjøs. "Yunus and Grameen Bank have shown that even the poorest

of the poor can work to bring about their own development,"

the Nobel Committee said in its citation.

Today the

bank claims to have 6.6 million borrowers, 97 per cent of them

women, and provides services in more than 70,000 villages in

Bangladesh. Its model of micro-financing has inspired similar

efforts around the world. "Micro-credit has proved to be an

important liberating force in societies where women in

particular have to struggle against repressive social and

economic conditions," the Nobel Committee noted.

Prof

Yunus and the bank will share in the $1.4 million prize as

well as a gold medal and diploma (The Daily Star, October 14,

2006).

Nobel Laureate Professor Muhammad Yunus termed the accolade

a great pride for the country and said it will encourage him

further to dedicate himself for improving the lives of the

poor. Soon after hearing the news of getting the Nobel Peace

Prize, professor Yunus said a world free from poverty is his

dream and he will work to make Bangladesh as a poverty-free

nation.

The entire nation went euphoric as soon as

international media reported on Friday afternoon that

Professor Muhammad Yunus had won this year’s Nobel peace

prize. The proud nation greeted him for his being the

first-ever Bangladeshi to win a Nobel prize as well as for his

accomplishment and that of his famed Grameen Bank. People from

all walks of life—from the head of state to the homeless, from

learners to professionals—greeted the news with joy.

|

Helen Todd spent a year in two villages in Bangladesh following

the lives of women who have been borrowing from the Grameen Bank for

a decade. She focuses on the day-to-day processes of how they

generate money from their tiny loans, what they do with the

resulting income, and how much control they retain over it. In stark

contrast with nonmembers, most Grameen women emerge from this study

as strong individuals, successfully battling for positions of power

in their families and for respect in their villages. Moreover, the

Grameen women's gains have been sustainable, since most of them have

invested in access to land. Through the vivid stories of individual

women, Todd paints a picture of women empowering themselves with the

crucial ingredient of continued access to credit over the course of

a decade (Dhaka Courier, 17 November, 2006).

Back to

Content

2. Conventional bank do not lend to the poor

Bangladesh, experts and others say, is less poor than we

think. Yet few are convinced, and nobody tells us who can make us

smile. Once the state could control prices to some degree, but in

this laissez-faire world of non-accountability the free market

becomes an excuse for not keeping misery under control. If nobody

can keep the prices down, of what use is the state, anyway. Might as

well hand the state over to the "syndicate" or an NGO or whoever,

some might say. Bangladesh, experts and others say, is less poor than we

think. Yet few are convinced, and nobody tells us who can make us

smile. Once the state could control prices to some degree, but in

this laissez-faire world of non-accountability the free market

becomes an excuse for not keeping misery under control. If nobody

can keep the prices down, of what use is the state, anyway. Might as

well hand the state over to the "syndicate" or an NGO or whoever,

some might say.

In Bangladesh the poor brown trash are

impossibly hungry. At least 25 percent of the people are half-fed,

often unfed. Between 1972 and 2006, we have been able to manufacture

a new category of wretched people, the extreme poor. These people

own endless mouths which chew on nothing because their jaws find no

food. Economic abstraction makes good fodder for seminars, but it

doesn't make that much sense where the hunger grows. These people

are the colour-coded poor. They carry cards to identify their status

of extreme poverty. These cards, one hopes, will give them access to

the facilities of the state. It's a plea, not a demand. In their

world, rights have limited meaning. The system is built on

occasional morsels of mercy from the state. There is a feeling that

it might be best to keep a distance from the powerful. Nobody is

quite sure about the grammar the state uses to talk to the poor.

"The poor are so poor that we can get nothing from them.

They have nothing to be robbed of. If their lives improve, the

criminals will go after them and that will make our lives insecure.

Should we work to help them?" This is the grammar of a society's

language, where impoverishment has become a protection from

criminals, a collective security blanket of sorts. The poor have

finally become too poor to cause any worry (Afsan Chowdhury,

November 2006).

What actually are the characteristics of these "Poor People"?

Basically they are that part of the society who are relatively most

deprived from income, wealth, education, social security and

political power. They are the defeated victims of an unequal

competition in an intrinsically unequal society. In Bangladesh there

is going on a continuous process of unequal and unjust competition

through which a greater section of the middle class is slowly

becoming the member of a lower middle class and after a brief period

of life and death struggle to hold on they also ultimately in most

cases slide down to swell the ranks of the poor. Now days in the

literature you will find another category: "Poor Becoming Extreme

Poor!"

Conventional banks, however, do not

lend to the poor. Banks require collateral and have complicated

procedures that the poor cannot satisfy. The poor are therefore

exploited by money-lenders and traders who operate a system of usury

in villages which is equivalent to bonded labour and slavery. In

another difference with normal banks, ‘Grameen Bank branches are

located in rural areas, whereas the branches of conventional banks

usually locate themselves as close as possible to the business

districts and urban centres. In perhaps the biggest difference, the

first principle of Grameen banking is that clients should not go to

the bank, it is the bank that should go to the people. Conventional banks, however, do not

lend to the poor. Banks require collateral and have complicated

procedures that the poor cannot satisfy. The poor are therefore

exploited by money-lenders and traders who operate a system of usury

in villages which is equivalent to bonded labour and slavery. In

another difference with normal banks, ‘Grameen Bank branches are

located in rural areas, whereas the branches of conventional banks

usually locate themselves as close as possible to the business

districts and urban centres. In perhaps the biggest difference, the

first principle of Grameen banking is that clients should not go to

the bank, it is the bank that should go to the people.

General features of Grameencredit are :

a) It promotes credit as a human right.

b) Its mission is to help the poor families to help themselves

to overcome poverty. It is targeted to the poor, particularly poor

women.

c) Most distinctive feature of Grameencredit is that it is not

based on any collateral, or legally enforceable contracts. It is

based on "trust", not on legal procedures and system.

d) It is offered for creating self-employment for

income-generating activities and housing for the poor, as opposed

to consumption.

e) It was initiated as a challenge to the conventional banking

which rejected the poor by classifying them to be "not

creditworthy". As a result it rejected the basic methodology of

the conventional banking and created its own methodology.

f) It provides service at the door-step of the poor based on

the principle that the people should not go to the bank, bank

should go to the people.

g) In order to obtain loans a borrower must join a group of

borrowers.

h) Loans can be received in a continuous sequence. New loan

becomes available to a borrower if her previous loan is repaid.

i) All loans are to be paid back in instalments (weekly, or

bi-weekly).

j) Simultaneously more than one loan can be received by a

borrower.

k) It comes with both obligatory and voluntary savings

programmes for the borrowers.

A member is considered to have moved out of poverty if her

family fulfills the following criteria:

1. The family lives in a house worth at least Tk. 25,000

(twenty five thousand) or a house with a tin roof, and each member

of the family is able to sleep on bed instead of on the floor.

2. Family members drink pure water of tube-wells, boiled water

or water purified by using alum, arsenic-free, purifying tablets

or pitcher filters.

3. All children in the family over six

years of age are all going to school or finished primary school.

4. Minimum weekly loan installment of the borrower is Tk. 200

or more.

5. Family uses sanitary latrine.

6. Family

members have adequate clothing for every day use, warm clothing

for winter, such as shawls, sweaters, blankets, etc, and

mosquito-nets to protect themselves from mosquitoes.

7. Family

has sources of additional income, such as vegetable garden,

fruit-bearing trees, etc, so that they are able to fall back on

these sources of income when they need additional money.

8.

The borrower maintains an average annual balance of Tk. 5,000 in

her savings accounts.

9. Family experiences no difficulty in

having three square meals a day throughout the year, i. e. no

member of the family goes hungry any time of the year.

10.

Family can take care of the health. If any member of the family

falls ill, family can afford to take all necessary steps to seek

adequate healthcare.

Grameen Bank has been effective because it has been

designed to be supportive of the needs of the poor. Grameen Bank

does not require its members to be literate and its rules are

simple. Each loan is disbursed without collateral with a collection

of principal, interest and savings on a weekly basis, to make

payments easy and manageable. A group mechanism ensures that each

member is part of a system of peer support. Centre meetings take

place at which members gather at their own doorstep to repay their

loans and discuss their projects. The meetings help create an

inter-linking network for the members and ensure an accountable and

transparent system.

|

When the whole country is going on a shopping frenzy (eid

festival), models in flashy designer clothes adorning pages of

different magazines and newspapers trying to coax customers

into buying the latest Hindi-film inspired kameez or sari,

there exist in this city hundreds and thousands of children,

lost and abandoned, who have to struggle day and night to make

ends meet. This is a story of sheer exploitation and utter

indifference; a story where mothers are forced to sell their

newborns for the price of a two-litre mineral water bottle; a

story where children start working as young as five to grow up

stunted and malnourished. |

The sixteen decisions

While providing small loans to the poor is an economic

intervention,

a Grameen Bank loan begins a process of deep transformation in

the lives of its members.

The poor women work hard to bring a host of positive changes in

their lives as their economic condition improves.

The aspirations of the members became incorporated into Grameen

Bank's Sixteen Decisions:

a social charter which the members themselves developed,

encompassing issue such as keeping family size small,

sending children to school, eating green vegetables, drinking

clean water, and

keeping the environment clean.

Today, all the children of Grameen

Bank members are in school. Studies show that Grameen Bank members

have lower birth rate than non-members. Their housing is better and

the use of sanitary latrines is higher than non-members. Their

participation in social and political activities is higher than that

of non-members, and reflects how seriously the members implement

these decisions. Today, all the children of Grameen

Bank members are in school. Studies show that Grameen Bank members

have lower birth rate than non-members. Their housing is better and

the use of sanitary latrines is higher than non-members. Their

participation in social and political activities is higher than that

of non-members, and reflects how seriously the members implement

these decisions.

Back to

Content

3. Credit for the ultra-poor

82

percent of the people live on less than $2 a day - Inefficient and

ineffective government and incongruent external influence .

To explode the myth that micro-credit is not useful for the

poorest of the poor, Grameen Bank began in 2004 a programme to give

loans exclusively to beggars. When GB invites beggars to join the

program, it does not discourage them from begging, instead the bank

offers them the option of carrying popular consumer items, financed

by Grameen Bank, when they go out from house to house. They may

choose to beg or sell the items at their convenience. If they find

that their selling activity picks up, they may quit begging and

focus on selling. Till October of this year, 52,000 beggars had

joined the programme. Typical loan to a beggar is about $10, with no

fixed terms of repayment.

Out of 261 women SCG members present in various group

discussions, it was possible to collect accurate information on the

use of loans for 201 women. The percentages in Table 1 add up to

more than 100, since loans are used by individuals for a number of

purposes at the same time. Along with that, numerous sources of

funds are put together for, say buying land or other assets, and

even for investment in various enterprises.

Use of Loan by 201 Women SCG Members

|

Number |

Percentage |

| Agriculture |

77 |

38 |

| Poultry |

54 |

27 |

| Large livestocks |

54 |

27 |

| Grocery shops |

10 |

5 |

| Vegetable selling |

25 |

13 |

| other small business |

14 |

7 |

| Transport/firewood/powerloom |

9 |

4 |

| Homestead |

10 |

5 |

| Housing improvement |

20 |

10 |

| Total respondents |

Total respondents |

|

What stands out from Tables 1 is the

predominance of agriculture and related activities in the areas of

livelihood investment – crops, poultry, livestock and vegetables.

Non-agriculture based activities, which include small business, like

tailoring shops, and the clearly men-operated sectors of transport,

firewood and powerloom, all together account for just 15 per cent of

loan uses; adding the 14 per cent in small business, that gives a

total of 29 per cent loans used by men. The possibly more accurate

projectwide figures on main use of loans account for 35 per cent of

loan uses in men’s activities, if we take all non-agriculture

related activities as being men’s activities. What stands out from Tables 1 is the

predominance of agriculture and related activities in the areas of

livelihood investment – crops, poultry, livestock and vegetables.

Non-agriculture based activities, which include small business, like

tailoring shops, and the clearly men-operated sectors of transport,

firewood and powerloom, all together account for just 15 per cent of

loan uses; adding the 14 per cent in small business, that gives a

total of 29 per cent loans used by men. The possibly more accurate

projectwide figures on main use of loans account for 35 per cent of

loan uses in men’s activities, if we take all non-agriculture

related activities as being men’s activities.

Women operate largely in the farm sector, and men much more in

the non-farm sector. Women and men may work together to prepare the

land, but all post-harvest tasks are carried out by women [Chen

1985, Mallorie 2003]. Vegetable production, as also raising poultry

and livestock, have traditionally been women’s activities. Women

report that in general they have better control over the income from

these activities.

There are a few instances of jointly run

enterprises. In one case the poultry business was run jointly by a

woman and her husband. Grocery shops tend to be run by men, but

there are several cases where the shop was close to the house, or in

the village and the women then fully shared the work of running the

shop. There are some outstanding cases of women who, through the

loans have become owners of small businesses and run them as owners

and managers.

Transforming Domestic into Commercial Activity

Where women themselves use the loans, they are invested in a

number of income generating activities – rearing poultry, goats and

cows, homestead vegetable and fruit gardening, pond fish culture,

etc. At one level this is a continuation of activities that women

were already carrying out. The earlier activities, however, were

carried out on a smaller scale, and that too for household

self-consumption. With credit provision there is the new requirement

of repayment, which requires that activities earn cash. This leads

to the transformation of the nature of the activity, even if the

type of labour does not change. Thus, what was in scale a petty and

domestic activity for household self-consumption is upgraded in

scale and changed in nature into a commercial activity for sale.

The critical difference that microcredit to women has made in

patriarchal Bangladesh is that it enabled women themselves to be the

agents of the transformation of a domestic activity for household

consumption into a commercial activity for sale. While the location

or site of this labour may not have changed and remained within the

homestead, the nature of the productive activity changed from being

private production for household-consumption to commercial activity

for sale. Since this transformation was carried out through the

medium of women’s own loans, women thereby remained not just the

labourers, but were also identified as the agents of this

transformation.

Before the microcredit system took root, all of women’s labour

remained within the definition of domestic work, work done for the

care and service of the household. Within this there was no

distinction between so-called productive and domestic/unproductive

tasks. All tasks undertaken by women were uniformly regarded as

being within the realm of domestic labour. But when the product of

this labour became a commodity and the result of it a cash income,

and when this transformation was carried out by credit taken by

women, the very nature of this part of women’s labour in the

household was transformed. It acquired social recognition and,

importantly, women’s own self-recognition as income earners.

We noted several instances of women members who used credit to

buy cows, poultry birds, trees, shops and agricultural lands in

their own names, and not in the name of the husband or son. In one

case nine women and in another case 10 women jointly leased a piece

of agricultural land for vegetable and crop production. They work

jointly on such lands and equally share the produce and cash earned

through sale in the local markets.

“… the family realises that she is the source of this income.

This increases her status and bargaining in the household … Some of

the women in the study perceived a decrease in physical violence

against them around the time of credit group meetings. One women

said that her family was worried that she might retaliate by

refusing to get another loan. n other words, even in being the

conduit for credit, women increase their influence in the household.

This increased influence of women who bring credit into the

household have, is expressed in a number of ways. “Now that I give

him money, he loves me more.” Or, “He listens to me more in deciding

how to spend household money.” Or, “We have been talking to you for

two hours. This would never have happened if we had not given money

to our husbands. They would not have allowed us to sit in a meeting

for this long,” said Maiful, (Mirzapur,Tangail).

How does the micro-credit system work?

A bank branch is set up with a branch manager and a number of

center managers and covers an area of about 15 to 22 villages. The

manager and the workers start by visiting villages to familiarise

themselves with the local milieu in which they will be operating and

identify the prospective clientele, as well as explain the purpose,

the functions, and the mode of operation of the bank to the local

population,’ explains Mohammed Shahjahan, general manager of

commerce, monitoring and evaluation at GB.

Groups of five

prospective borrowers are formed in the first stage and only two of

them are eligible for, and receive a loan. The group is observed for

a month to see if the members are conforming to the rules of the

bank. Only if the first two borrowers begin to repay the principal

plus interest over a period of six weeks, do the other members of

the group become eligible themselves for a loan. ‘Because of these

restrictions, there is substantial group pressure to keep individual

records clear. In this sense, the collective responsibility of the

group serves as the collateral on the loan. The Grameen Bank is

based on the voluntary formation of small groups of five people to

provide mutual, morally binding group guarantees in lieu of the

collateral required by conventional banks.

Loans are small,

but sufficient to finance the micro-enterprises undertaken by

borrowers: rice husking, machine repairing, purchase of rickshaws,

buying of milk cows, goats, cloth, pottery etc. The interest rate on

all loans is 16 per cent. Although mobilisation of savings is also

being pursued alongside the lending activities of the Grameen Bank,

most of the latter’s loanable funds are increasingly obtained on

commercial terms from the central bank, other financial

institutions, the money market, and from bilateral and multilateral

aid organisations.

‘Intensive discipline, supervision, and

servicing characterize the operations of the Grameen Bank, which are

carried out by “Bicycle bankers” in branch units with considerable

delegated authority,’ he adds. The rigorous selection of borrowers

and their projects by these bank workers, the powerful peer pressure

exerted on these individuals by the groups, and the repayment scheme

based on 50 weekly installments, contribute to operational viability

to the rural banking system designed for the poor. Savings have also

been encouraged. Under the scheme, there is provision for 5 percent

of loans to be credited to a group find and Tk 5 (70 Tk= 1 US

Dollar$) is credited every week to the fund.

Back to

Content

4. Extension and Interaction with Officials

Dealing with NGO and project officials is something to be

expected when women become members of the grameen bank. But what is

of interest is to note that other officials, like agricultural

extension officers, also contact these women, which means that they

recognise the role of these women in actually carrying out and

managing certain types of agricultural production. It is no longer

the male “head of the household” who is supposed to be the recipient

of extension messages. The women were proud that they were being

contacted by officials and various technical matters were discussed

with them, and not with their husbands. “Now the block supervisor

comes to meet us, not our husbands,” (Narsinghdi). In Kaliganj,

Gazipur, it was pointed out because of women’s involvement in both

the ownership of land and in field labour, extension officers now

visit and discuss technical issues with the women. This is in sharp

contrast to the experience of the early 1990s, when, for instance,

in IFAD’s Agricultural Diversification Project (MSFDCIP) in

Kurigram, extension effort was confined to men.

Back to

Content

Improvements in Well-Being

|

The fishes find the deep sea,

The birds

the branches of the tree.

The Mother knows her love for

her son

By the sharp pain in her heart alone

Many

diverse the colour of cows,

But white the colour that all

milk shows,

Through all the world, a Mother's name -

A

mother's song is found the same

Jasim Uddin, The

field of the Embroidered Quilt

Translated

by E. M. Milford

|

|

|

An increase in consumption is to be

expected with an increase in income. Along with a quantity increase

there is also a quality increase in food consumption. Almost

invariably women said that while they earlier had a little vegetable

and not much more with each meal, now they consume more vegetables,

and also eggs and fish once a week each, dal twice a week, and

chicken or beef, once a month, (Bhuapur and Raipura, Narsinghdi). In

another SCG, it was said that they earlier ate fish or meat just

once a month, but now they could afford these once a week. Another

group said that while earlier they ate fish or meat only two or

three times in a month, now their children have milk and eggs almost

daily, (Delduar, Tangail). An increase in consumption is to be

expected with an increase in income. Along with a quantity increase

there is also a quality increase in food consumption. Almost

invariably women said that while they earlier had a little vegetable

and not much more with each meal, now they consume more vegetables,

and also eggs and fish once a week each, dal twice a week, and

chicken or beef, once a month, (Bhuapur and Raipura, Narsinghdi). In

another SCG, it was said that they earlier ate fish or meat just

once a month, but now they could afford these once a week. Another

group said that while earlier they ate fish or meat only two or

three times in a month, now their children have milk and eggs almost

daily, (Delduar, Tangail).

Further, it would seem that in the matter of food, there is no

clear discrimination against the girl-child. Girls get eggs or milk

as frequently as boys do. Overall, as we will discuss later in this

paper, there is clearly a substantial rise in the status of girls,

reflected in the higher enrolment of girls than boys in school.

In the use of income from credit-based enterprises, women

mentioned a greater expenditure for food, clothes, children’s

education, and health, including their own. Women routinely have

more clothes than they had earlier, and more clothes than their

mothers did.

Greater expenditure on health does not in

itself mean better health, but it does show an increased ability to

respond to health problems. Further, with women now recognised as

income earners, there could also be a greater willingness to use

still limited household income for tending to women’s health. The

necessity of making regular, weekly instalments imposes a need to

sustain the income-earning activities from which the payments are

made. This discipline of the market, concretised through the credit

system has been impressed on the routines of household work and

economics, and is also reflected in the rather high usage of

contraceptives in rural Bangladesh.

Improvements in well-being are also reflected in home

improvements. The major home improvements are the substitution of a

tin roof for a thatched one and the addition of some furniture (a

bed, table and chairs), which are now quite common in rural

homes.

Back to

Content

6. Household Decision-Making

From the fact that a part of household

income now accrues to or through women, one would expect a greater

participation of women in household decision-making. Women generally

report such greater participation. There was more consultation with

women, rather than the earlier unilateral decision-making by men. In

cases where women used credit money to run their own

micro-enterprises, they said that they had more of a say than in

cases where they gave the money to their husbands or sons. From the fact that a part of household

income now accrues to or through women, one would expect a greater

participation of women in household decision-making. Women generally

report such greater participation. There was more consultation with

women, rather than the earlier unilateral decision-making by men. In

cases where women used credit money to run their own

micro-enterprises, they said that they had more of a say than in

cases where they gave the money to their husbands or sons.

Where women themselves carried out the sales, which meant it

was done at the doorstep, women directly got the income and could

decide on how to spend it, generally for various household needs,

including food and children’s educational needs. But even when men

did the final marketing, women said that the sales income was given

to them.

Women also thought that the availability of more

money led to less conflict on how to use it, and that women could

have a greater say in the manner of spending household income.

Earlier they could say nothing, or risked a beating if they objected

to the manner in which income was being spent. Now, “I can show some

temper and the man listens to me,” (Sreepur, Gazipur).

Earlier men decided even on choice of saris and other clothes,

with little regard to what women themselves preferred. But women

reported a change in the manner of buying clothes, etc. “If you have

no money, there is no value for your choice. Now I go with my

husband to buy my sari,” (Mirzapur, Tangail). Sufia’s husband took

her to the market so that she could buy the salwar-kameez of her

choice. This happened in the case of buying jewellery too. Women go

to the market with their husbands. They choose the items they want

and also make the payment. Husbands are there just to accompany

them.

With women now earning some of the household cash income it

should be possible for women to give presents to members of their

natal families. Did this actually take place? In every group there

were clear statements that members did in fact make such presents,

particularly to their mothers. “Sometimes we buy small gifts for our

mothers or others staying in the natal home.” Or, “We buy gifts for

our parents’ family, particularly for our mothers,” (Raipura,

Narsinghdi). This is something that they could not do earlier, when

they themselves were not earning the family’s cash income and

clearly shows the increased influence women have over the use of

household income, including its use to maintain the matri-social

networks on which they can rely in times of crisis.

Back to

Content

7. Samman/Dignity

Many of the points made above show that there is an

increased self-esteem and enhanced dignity, both within the

household and within society, for these women. The women point out

that their men consult them much more than earlier. Instead of just

buying any clothes for their wives, now they would ask for their

preferences before going to the market. Of course, in a number of

cases women themselves were going to the market to buy their own

clothes. Many of the points made above show that there is an

increased self-esteem and enhanced dignity, both within the

household and within society, for these women. The women point out

that their men consult them much more than earlier. Instead of just

buying any clothes for their wives, now they would ask for their

preferences before going to the market. Of course, in a number of

cases women themselves were going to the market to buy their own

clothes.

As part of the increased dignity, was the reported

reduction in men’s violence in the home. “Violence has reduced. And

now husbands even respect (salute) us. Also sons and daughters

respect us,” a woman from Narsinghdi.

The reduction of

domestic violence was mentioned in virtually every group. As it was

put in one group. “We were in fire; now we are in water,” (Kaliganj,

Gazipur) i e, in a relatively better position, though not as good as

dry land. Women further said, as mentioned earlier, that now they

could also talk or even shout back at their husbands, which would

have been unthinkable before they began to get credit and earn an

income.

Solidarity and Groups

bThe possibility of members of SCGs standing for

and winning elections to local councils clearly depends on

solidarity within the group. The group is needed to gather the

strength to contest, to conduct the election campaign and to vote

and secure other votes in the election. Particularly for someone

from the poorer sections of society such an effort would be

impossible without a group. bThe possibility of members of SCGs standing for

and winning elections to local councils clearly depends on

solidarity within the group. The group is needed to gather the

strength to contest, to conduct the election campaign and to vote

and secure other votes in the election. Particularly for someone

from the poorer sections of society such an effort would be

impossible without a group.

But it is not only with respect

to such clearly group activities that the group is needed. Group

solidarity is needed to help women who are opposed in some

activities, or even in unrelated matters, by their husbands. Dealing

with domestic violence, and marital discord with the threat of

divorce (something on which men in Bangladesh very much have the

upper hand) are difficult at the individual level. Group

intervention is needed to protect women from eviction from their own

houses.

This the groups have done to quite an extent.

“Women’s solidarity in the samiti has increased a great deal. In one

case they took to task a husband who was rough with his wife, a

member of the samiti,” (Sreepur, Gazipur). “We have developed group

solidarity and identity as members of the samiti, which we have used

to prevent the taking of second wives by two men in this village. I

am also raising this (membership of the samiti) as a major point in

negotiating the marriage of my daughter,” Rashida, along with other

members of the SCG, (Tangail).

Back to

Content

8. The Market

The market has traditionally been the most taboo area for women.

This is so not only in purdah ridden Bangladesh, but also in most of

the Indo-Gangetic belt, including north India and Pakistan. Women

who go to the market lose social standing. If women do have to go to

the market, they should be as quick about it as possible.

Women may directly sell minor items, such as eggs and

vegetables, either at their doorsteps to itinerant traders or

through children taking them to market. Otherwise, they give the

produce to their husbands or other male members of the family who

take the produce to the market

Where there is a major change, however, is in going to the market

to buy something, like clothes for themselves and their children,

schoolbooks, cosmetics, jewellery, etc. Going to the market for such

purposes, either accompanied by their husbands or as a group of

women, has become a regular feature of women’s activities.

Back to

Content

9. Savings

Women have three forms of savings – gold

jewellery, cash savings and in NGO account. The first is bought with

the full knowledge of their men. But there is a strong tendency to

hide any cash savings from their husbands and sons. This is not

something new in Bangladesh, where rural women have a long-standing

practice of ‘secret’ savings [Kabeer 2001: 75]. Women have three forms of savings – gold

jewellery, cash savings and in NGO account. The first is bought with

the full knowledge of their men. But there is a strong tendency to

hide any cash savings from their husbands and sons. This is not

something new in Bangladesh, where rural women have a long-standing

practice of ‘secret’ savings [Kabeer 2001: 75].

Traditionally jewellery was bought with ‘men’s money’,

ignoring women’s contribution to the household well-being. In the

event of divorce women were expected to leave everything they had,

except for the set of clothes they would wear, and that would be the

worst set they had. Any gold jewellery would remain behind with the

husband.

The other factor is that women might expect that since the

jewellery has been bought with their own money, they would be able

to claim the jewellery in the event of divorce.

Back to

Content

10. Village phone programme

Professor Yunus has long argued that

information and communications technology (ICT) has the potential to

bring unprecendented employment opportunities for the poor. GB's

Village Phone Project is an extraordinary example of how powerful

ICT can be in the hands of the poor. A Grameen borrower receives a

handset with Grameen Bank financing and becomes the telephone-lady

of the village, selling telephone services to the villagers, usually

in places where fixed lines did not exist. In the process, she makes

an income on average higher than twice the national per capita

income. By October 2005, Grameen had provided more than 172,000 poor

women with mobile phones for income generation in villages across

Bangladesh. Professor Yunus has long argued that

information and communications technology (ICT) has the potential to

bring unprecendented employment opportunities for the poor. GB's

Village Phone Project is an extraordinary example of how powerful

ICT can be in the hands of the poor. A Grameen borrower receives a

handset with Grameen Bank financing and becomes the telephone-lady

of the village, selling telephone services to the villagers, usually

in places where fixed lines did not exist. In the process, she makes

an income on average higher than twice the national per capita

income. By October 2005, Grameen had provided more than 172,000 poor

women with mobile phones for income generation in villages across

Bangladesh.

Back to

Content

11. Pension fund and other savings

In recent years, Grameen Bank has introduced a range of

attractive new savings products for borrowers. The personal and

special savings accounts of old remain, but have been made more

flexible in terms of facilities available to them. GB has also

introduced pension deposit fund which enables the member to receive,

after a ten year period, a guaranteed amount which is almost double

the amount she has put in over that time. In October 2005, GB's

deposits total $441 million of which $282 million are its members

deposits. The savings products of Grameen Bank II are enabling not

only its members to become self reliant but has paved the way for

Grameen Bank's own self reliance.

Back to

Content

12. Self-reliance for GB

In 1995, GB decided not to receive any more donor funds, since

which time it has not requested any fresh funds from donors. The

last installment of donor fund which was in the pipeline was

received in 1998.

Today, Grameen Bank's total of outstanding

loans is approximately $405 million. Deposits as a percentage of

outstanding loans today is 109 percent. If it takes into account its

own resources as well as deposits, this percentage is 131 percent.

Since Grameen Bank came into being, it has made profit every year

except in 1983, 1991, and 1992. GB does not foresee having to take

any more donor money or even take new loans from internal or

external sources in future. GB's growing deposits will be more than

sufficient to repay its existing loans, and run and expand its

credit programme.

Back to

Content

13. High Cost of Microcredit

One of the complaints frequently made by women was that the cost

of credit from the NGOs was very high and should be brought down.

The other main complaint was that the loan given was very small,

with the concomitant demand that the loan limit should be

increased.

The now-standard rate of interest charged by NGOs

is 15 per cent. What makes it even higher is that while repayments

are collected weekly, meaning that 2 per cent of the principal is

returned every week, the interest rate is calculated over the whole

year on the full amount of the loan, and not on the outstanding

balance, as is the practice with commercial bank loans. This makes

the effective rate of interest over the whole year, amount to 30 per

cent. NGOs themselves admit that this is the possible actual rate of

interest [Ahammed 2003]. Where repayments are not fully collected

weekly the rate of return on NGO loans may fall to about 24 per

cent.

The NGOs justify this high rate of interest on the

basis of the high cost of supervision of microcredit [Ahammed 2003].

The cost of supervision of small loans with weekly repayments is

certainly higher than it is in the usual commercial bank

loans.

Often the members protest to pay high interest,:Micro-credit

and rural women and many cases it is misused but still

better than local money lenders.

Back to

Content

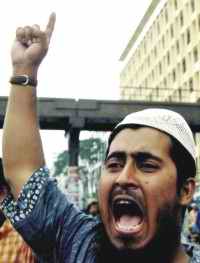

14. The Struggle for Survival and Credibility among the

Religious NGOs (Non-Governmental Organizations) in

Bangladesh

Many activist women understand Bangladesh as a

country that should encourage women's equality and promote harmony

between people of different faiths. Tragically, they face tremendous

opposition from religious figureheads along with the threats and

fatwas- was that fundamentalist insanity is gaining notoriety for.

Fatwas are proving quite effective in gaining results for ambitious

fundamentalist leaders world- wide, who deem explorative thought as

anathema to religious principles. Many activist women understand Bangladesh as a

country that should encourage women's equality and promote harmony

between people of different faiths. Tragically, they face tremendous

opposition from religious figureheads along with the threats and

fatwas- was that fundamentalist insanity is gaining notoriety for.

Fatwas are proving quite effective in gaining results for ambitious

fundamentalist leaders world- wide, who deem explorative thought as

anathema to religious principles.

For women, increasing fundamentalism in Bangladesh is a

threat to the little rights and freedoms that they currently have.

Women are already repressed by gender-biased social norms and

extreme poverty. Fundamentalist ideology could have detrimental

effects on women, and succeed in excluding and marginalizing them

even further. Eliza Griswold spoke with Mufti Fazlul Haque Amini,

who has served as a member of Parliament for the past three years.

She reported him saying that “he believes that secular law has

failed Bangladesh and that it’s time to implement Sharia, the legal

code of Islam”. This may not occur formally, but within the social

fabric of Bangladesh, and coupled with a legal system that

consistently fails to address issues of rape, torture and murder,

women are threatened both physically and emotionally, as well as

being crippled economically – due to increasing fundamentalist

forces within the country.

Biased mentalities that do not recognise women as equal citizens

could be compounded by localized Sharia interpretations of Islam,

where family laws “frequently require women to obtain a male

relative’s permission to undertake activities that should be theirs

by right. This increases the dependency women have on their male

family members in economic, social, and legal matters.

Since the independence of Bangladesh in 1971, the state has

largely failed to assist the poor or reduce poverty, and NGOs

have grown dramatically, ostens ibly to fill this gap. There are

more and bigger NGOs here than in any country of equivalent size.

The target group approach has allowed NGOs in Bangladesh to work

successfully with the rural poor and provide inputs to a

constituency generally bypassed by the state .

This

innovation led to a concentration of efforts into small-scale,

home-based income-generating activities such as cattle and

poultry-rearing, food processing, social forestry, apiculture and

rural handicrafts, combined with the provision of microcredit, to

which the landless had previously been denied access except from

local moneylenders at high cost. Recently, most NGOs in Bangladesh

have taken microcredit as their major activity, which has resulted

in resistance from some religious leaders and organisations.

Charging of interest is forbidden in Islam. NGOs said the

fundamentalists had objected to Muslim women going out to work.

Other NGO activities like non-formal schools for children and trees

planted by NGO clients have also been attacked. While religion and

development were considered to be two distinct categories with no

overlap for the better part of the 20th century, their

interdependence came to be recognized during the last decade. In

Bangladesh the link between religion and development is even more

evident, because religious and spiritual leaders have a great hold

on people’s hearts and actions. They can trigger impulses leading to

sustainable development or mar development through fundamentalist

attitudes. In Bangladesh, there is a general view that RNGOs are

well funded from outside. It is believed that Islamic NGOs are

funded by state agencies and NGOs of the oil-rich Gulf countries,

Christian missionary NGOs from their fellow Churches and their

followers.

An independent US panel on religious freedom expressed concern

Tuesday over growing Islamist militancy in Bangladesh and violence

against individuals and groups perceived as ‘un-Islamic.’ Bangladesh

could be a model for other emerging democracies with majority Muslim

populations but ‘that model is in jeopardy,’ warned Felice Gaer,

chairwoman of the US Commission on International Religious Freedom,

a bipartisan federal agency. She warned about ‘growing Islamist

militancy and the failure to prosecute those responsible for violent

acts carried out against Bangladeshi individuals, organisations and

businesses perceived as ‘un-Islamic.’,(New Age, October 19, 2006).

The

Shariah, Mullah and Muslims in Bangladesh

Back to

Content

15. CONCLUSION

A study by World Bank economist Shahid Khandker in

2005 suggests that micro-finance contributes to poverty reduction,

especially for female participants, and to overall poverty reduction

at the village level in Bangladesh. Micro-finance thus helps not

only poor participants but also the local economy. Grameen Bank's

own internal survey based on 10 objective indicators shows that 55

percent of its members have already crossed the poverty line. A study by World Bank economist Shahid Khandker in

2005 suggests that micro-finance contributes to poverty reduction,

especially for female participants, and to overall poverty reduction

at the village level in Bangladesh. Micro-finance thus helps not

only poor participants but also the local economy. Grameen Bank's

own internal survey based on 10 objective indicators shows that 55

percent of its members have already crossed the poverty line.

A Social Change needs also Political Change

Yunus told the press (October 17, 2006) that he would ‘continue

his campaign for promoting clean and competent candidates in

national polls’, adding: ‘If necessary, I’ll form a political

party.’ He said there has been a suggestion that the campaign for

clean candidates will not be successful if its protagonists are not

part of the political process. ‘Is it too hard to form a party?’ he

asked the people present. The country is trapped in a political maze

and people are looking for a way out, observed Yunus. ‘We need to

break out of this maze. I am not saying that I will be successful.

But the effort should be made,’ he added. However, the Awami

League’s general secretary, Abdul Jalil, declined to say anything

about Yunus’ plan to float a political party, ‘if necessary’.

Nobel laureate Professor Muhammad Yunus’s wish to form a

political party evoked mixed reactions among political and civil

society circles. While some politicians refused to comment, others

reminded him of the difficulties involved in political activism. The

civil society leaders were also divided on the issue, with some of

them hailing the idea and others advising him to remain above

politics.

After two decades and more of NGO micro-credit based activity,

there is no longer an idea that women’s income-earning activities

are temporary and reversible. These new practices also have their

counterpart in new norms of status of women and thus the creation of

a new culture. As discussed below, there is a clear change in gender

norms and the creation of new norms of the non-exclusionary type.

Women have begun to think of new norms. On the whole, they

do not justify their practices in terms of the old norms of purdah,

or even as temporary deviations from the same. In discussions with

the women of the SCGs, it was repeatedly pointed out that samman or

respect no longer consisted of being in purdah. This repeated

assertion tells us that new norms are being created, more in

consonance with the new practices.

Who is a sammani mahila, a

woman of honour or respect? “A woman, who has land, education and

knowledge. Health is also important. We do not agree with the

traditional idea of purdah-nashin (women in purdah) as being

respected.” One woman of this group in fact said, “Purdah is like a

prison; one who stays at home, and whose resources are under the

control of husband or son is like a prisoner,” (Narsinghdi).

“One who is working outside the home has her own

money/independent earnings and is free to go anywhere. She must be

educated and also well behaved, she must not shout at or ignore the

poor and illiterate,” women said in chorus during field discussions

(Raipura, Narsinghdi).

The field of the changes were initially and still are primarily

economic, the development of various types of micro-enterprises,

etc. But the new types of practice in their humblest forms change

the very structure of the social conditions of production that “lead

the dominated to take the point of view of the dominant on the

dominant and on themselves” [Bourdieu 2001: 42]. What is the change

in the social condition of production? In the briefest manner this

can be expressed as a change in the social structure of accumulation

at the level of the household from having been a men-centred

accumulation, an accumulation in men’s hands, to an accumulation

that is also partly women-centred, some accumulation in women’s

hands.

But what gives us a clue to the far-reaching consequences of this

transformation is the manner in which gender norms of respect are

being re-created from glorifying purdah-nashin women or their

seclusion and dependence to valuing independent income, education,

work outside the home, mobility and professional engagement. As

women changed their practice, over time so too have they changed the

norms and the concepts with which they make sense of the world.

“Gradually and steadily, we will break all these shackles of

tradition that bind us as women,” says Nargis (a pregnant woman and

mother of three children) with the support of most members of an

UPAMA SCG. Savita, a member of another SCG in Kishoreganj, says, “If

I could provide education to my daughter, she would then become as

important as the son in the family”

Back to

Content

16. References

Yunus, M., August 2006,

Bhatti, K. 2005. “Political chaos, Islamic fundamentalism and

poverty”. Available from

http://www.socialistworld.net/eng/2005/02/10bangladesh.html

Asia News 2005. “People defend democracy against rise in Islamic

extremism”. 11 February 2005.

Kabeer, Naila (2000): The Power to Choose: Bangladeshi Women

Workers and Labour Market Decisions, Vistaar Publications, New

Delhi. – (2001): ‘Conflicts Over Credit: Re-Evaluating the

Empowerment Potential of Loans to Women in Rural Bangladesh’ in

World Development, Vol 29, No 1, pp 63-84.

Govind Kelkar, Dev Nathan, Rownok Jahan, Microcredit and Gender

Relations in Rural Bangladesh, EPW, 2004.

Morshed, L. , Feb 4, 2006, Rochelle Jones 27 May, 2005.

Asia News 2005. People defend democracy against rise in Islamic

extremism.

11 February 2005, The Daily Star.

Bengali Newspapers, Daily Ittefaque, Jugantor, Prothom Alo.

Ahammed, Iqbal (2003): ‘Rate of Interest in Micro-Credit Sector:

Comparing NGOs with Commercial Banks’, paper presented at

International Seminar on Attacking Poverty with Micro-Credit, PKSF,

Dhaka, January 8-9,

Rozario, Santi (2002): ‘Gender Dimensions of Rural Change’ in

Kazi Ali Toufique and Cate Turton (eds), Hands Not Land: How

Livelihoods are Changing in Rural Bangladesh, BIDS and DFID,

Dhaka

.

UNFPA (2003): ‘Assessment of Male Attitudes Towards Violence

against Women’, reported in The Bangladesh Observer, Dhaka, August

14.,2005)

Top of

Page

Last Modified:July 24, 2007 |

| |

The success of Grameen project

is entirely due to the responsiblity and participatation by

the women. Rabinranath Tagore knew this.

The success of Grameen project

is entirely due to the responsiblity and participatation by

the women. Rabinranath Tagore knew this.

In Bangladesh, the unintended

consequences of the microcredit system with NGOs as partners have

been far-reaching. The very structure of social production that

focused on 'man as the breadwinner' has changed to accommodate a

substantial and permanent role for women as income-earners.

In Bangladesh, the unintended

consequences of the microcredit system with NGOs as partners have

been far-reaching. The very structure of social production that

focused on 'man as the breadwinner' has changed to accommodate a

substantial and permanent role for women as income-earners. Grameen Bank was initiated in 1976 by

Professor Muhammad Yunus as an action research project of Chittagong

University. In a village near the university called Jobra, he found

that the poor did not have access to small amounts of capital to

engage or build on their tiny livelihood activities. The only source

of capital were loans from money- lenders at exorbitant rates of

interest. As an experiment, he began a project to provide small

loans to poor women in Jobra to engage in income generating

activities. In all cases, the poor women took loans from the

project, invested their money, and generated enough income to pay

back their loans and keep a profit.

Grameen Bank was initiated in 1976 by

Professor Muhammad Yunus as an action research project of Chittagong

University. In a village near the university called Jobra, he found

that the poor did not have access to small amounts of capital to

engage or build on their tiny livelihood activities. The only source

of capital were loans from money- lenders at exorbitant rates of

interest. As an experiment, he began a project to provide small

loans to poor women in Jobra to engage in income generating

activities. In all cases, the poor women took loans from the

project, invested their money, and generated enough income to pay

back their loans and keep a profit. The Grameen Bank operates on the premise that

the poor remain poor, not because they do not work or do not have

skills, but because the institutions created around them keep them

poor. Charity is not a solution to poverty, but rather fosters

dependency, thus perpetuating poverty. All human beings are born

with unlimited potential, and merely require an opportunity to

unleash that potential. Professor Yunus argues that credit provides

that opportunity and should therefore be considered a human

right.

The Grameen Bank operates on the premise that

the poor remain poor, not because they do not work or do not have

skills, but because the institutions created around them keep them

poor. Charity is not a solution to poverty, but rather fosters

dependency, thus perpetuating poverty. All human beings are born

with unlimited potential, and merely require an opportunity to

unleash that potential. Professor Yunus argues that credit provides

that opportunity and should therefore be considered a human

right. After independence in 1971 and

restoring democracy in ’91, Bangladesh witnessed the biggest

achievement as Professor Muhammad Yunus and his Grameen Bank

were declared yesterday to win the Nobel Peace Prize 2006 for

pioneering the use of micro-credit to benefit poor

entrepreneurs. Prof Yunus is the first Bangladeshi and also

the third Bangalee after poet Rabindranath Tagore and

economist Amartya Sen to win the Nobel Prize. Grameen Bank,

founded by Prof Yunus, has been instrumental by offering loans

to millions of poor Bangladeshis, many of them women, without

any financial security, in improving their standard of living

by starting businesses with the tiny borrowed sums

After independence in 1971 and

restoring democracy in ’91, Bangladesh witnessed the biggest

achievement as Professor Muhammad Yunus and his Grameen Bank

were declared yesterday to win the Nobel Peace Prize 2006 for

pioneering the use of micro-credit to benefit poor

entrepreneurs. Prof Yunus is the first Bangladeshi and also

the third Bangalee after poet Rabindranath Tagore and

economist Amartya Sen to win the Nobel Prize. Grameen Bank,

founded by Prof Yunus, has been instrumental by offering loans

to millions of poor Bangladeshis, many of them women, without

any financial security, in improving their standard of living

by starting businesses with the tiny borrowed sums

Yunus, dubbed "Banker to the

Poor", began fighting poverty during a 1974 famine in

Bangladesh with a loan of $27 out of his pocket to help 42

women buy weaving tools to save them from the clutches of the

moneylenders. "They got the weaving tools quickly, they

started to weave quickly and they repaid him quickly," said

Mjøs. "Yunus and Grameen Bank have shown that even the poorest

of the poor can work to bring about their own development,"

the Nobel Committee said in its citation.

Yunus, dubbed "Banker to the

Poor", began fighting poverty during a 1974 famine in

Bangladesh with a loan of $27 out of his pocket to help 42

women buy weaving tools to save them from the clutches of the

moneylenders. "They got the weaving tools quickly, they

started to weave quickly and they repaid him quickly," said

Mjøs. "Yunus and Grameen Bank have shown that even the poorest

of the poor can work to bring about their own development,"

the Nobel Committee said in its citation.  Bangladesh, experts and others say, is less poor than we

think. Yet few are convinced, and nobody tells us who can make us

smile. Once the state could control prices to some degree, but in

this laissez-faire world of non-accountability the free market

becomes an excuse for not keeping misery under control. If nobody

can keep the prices down, of what use is the state, anyway. Might as

well hand the state over to the "syndicate" or an NGO or whoever,

some might say.

Bangladesh, experts and others say, is less poor than we

think. Yet few are convinced, and nobody tells us who can make us

smile. Once the state could control prices to some degree, but in

this laissez-faire world of non-accountability the free market

becomes an excuse for not keeping misery under control. If nobody

can keep the prices down, of what use is the state, anyway. Might as

well hand the state over to the "syndicate" or an NGO or whoever,

some might say.  Conventional banks, however, do not