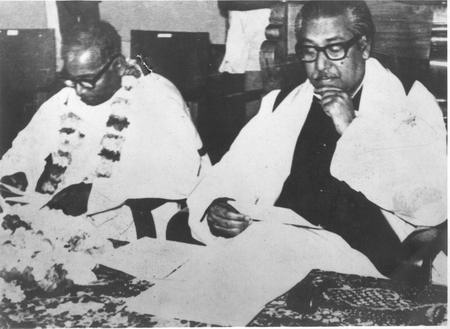

Jasim Uddin: American Folklife Center (AFC)'s First Collection of Bengali Folksong, Indian Folklife,

by JENNIFER CUTTING, Folklife Specialist, and STEPHEN WINICK, Writer-Editor, April 2011

In 1958, the American Folklife Center (AFC) Archive acquired its first recording of Bengali folksong. Fifty years later, AFC repatriated this material to Bangladesh, sending a copy to the Folk Culture Museum at Jasim Uddin House in Faridpur.

The repatriation reflected the American Folklife Center's ongoing and evolving commitment to the preservation and stewardship of intangible cultural heritage, and to providing communities of origin with access to their materials.

The field recording in question features Bengali folklorist and poet Jasim Uddin (1904-1976), known in Bengali as "Pallikabi," or "The People's Poet." It contains ten performances of Uddin singing traditional Bengali folksongs, and providing commentary and English translations for the collectors.The Jasim Uddin Recording: a Summary

Uddin organized his recording session according the life-cycle customs of Bangladesh. Hence, his fi rst selection is what he terms a "birth song," and this is followed by a children's song.

The latter demonstrates that Uddin was a traditional singer in his everyday life; upon hearing the recording, Uddin's son, Dr. Jamal Anwar, commented: "My father used to sing [this] to me. I still remember the song…."

The third piece is among the most interesting selections. It is a rain song, which, Uddin says, unmarried girls would sing while marching in a procession from house to house in times of drought. Interestingly, Uddin described this custom more fully in his poetry:

Into this village came a band of girls

At such a season of dearth;

Singing the song of the marriage of rain,

Th at rain might fall on the earth.

Five girls in a chain, five painted flowers,

But she is without compare,

Who stands in the centre in colour of gold,

The fairest of the fair. 1

Uddin then sings a rhythmic work song, which he states is for tasks "like pulling a boat for a long distance";

two war songs for "when the head man of the village is exciting his comrades to fi ght"; and a narrative song, "in which the King's daughter is dressing herself."

Following the narrative piece, Uddin sings a love song, and gives a full translation into English, including the following lines:

"Oh, my beloved friend,

had I known that there would be so much pain… I wouldn't have come under the branch of the cottonwood tree, and

I wouldn't have seen your beautiful face.

If you come to my house, people will scold thee.

But if you do not like to, don't come to my house,

but come to my neighbor's house and talk loudly so that

I can hear. And, my friend, wherever I go, whatever place I see… whoever sees me says:

‘This is the girl who has left house and hearth,

and fallen in love with a foreigner.'"Uddin's last performance is a mourning song. He explains that in all of the previous songs, the words are more prominent than the tunes. In the mourning songs, he says, the opposite is true, and the tune may be wordless:

"The village woman in East Bengal…when her daughter is dead, she cries loudly; she doesn't care whatever language may come to her mind; she shouts; only she is expressing her feelings with some tune."

Uddin sings the mourning song, and follows it with another that uses the same tune, prefacing the latter with the introduction:

"There is a little variation in this tune where the witch doctors are invoking the spirits from outside to punish them."

The duration of the recording is fourteen minutes and two seconds. In this brief span, Jasim Uddin provides us with Bengali songs on the most important themes of human life: birth and death, childhood and parenthood, love and conflict, nature and magic, the fertility of the earth and the ferocity of war.

He organizes the songs to illustrate the life cycle as lived in a Bengali village, revealing himself to be a knowledgeable tradition-bearer, as well as a thoughtful professor and scholar. Though the recording technique is crude by today's standards (e.g. the tape recorder is turned off after almost every song, which interrupts the continuity and causes the listener to miss parts of Uddin's explanations), the sound quality on the recording is very clear, allowing Uddin's musical and poetic mastery to shine.Jasim Uddin - Folklorist and Poet

Jasim Uddin was born on January 1, 1903, in Tambulkhana, a village in the Faridpur district of East Bengal. As he related in his 1964 autobiography Jibon Katha, Uddin began reciting and writing poems at a very early age. "After writing three or four of my couplets in the notebook I was astonished. There were fourteen syllables in every line and the last syllable of every line rhymed with the second line's last syllable….

Now that I had discovered how to fi nd a rhythm for my verse, who could hold me back?" By the time Uddin was a student at Faridpur Rajendra College, he had already won acclaim as a Bengali poet.

Uddin's poetry was rooted in the rural Bengali village life he knew as a child; his language was the language of the farmers, the fi shermen, the boatmen, and the weavers of Bengali country villages. Though he never achieved the international renown of his fellow Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, Uddin's work is well known throughout India and Bangladesh, and has been translated for school curricula in both countries.

It has also been translated into European languages, including English. Tagore himself admired Uddin, and wrote that "Jasim Uddin has opened a new school, a new language which is immortal."

At the time of Uddin's birth, eastern Bengal was part of British colonial India. During his childhood, it was severed from western Bengal and made a separate province (Eastern Bengal and Assam), which angered Bengali nationalists. Although the region rejoined the rest of Bengal in 1912, in 1947 it was again ceded to become East Pakistan.

In 1971, with help from neighboring India, this contested land became a sovereign nation, the People's Republic of Bangladesh. All of these tumultuous events occurred during Uddin's lifetime, and involved the religious division between Muslims and Hindus, as well as the lesser prestige and political power of Bengali language and culture relative to the majority cultures of India and PakistanAs a Bengali nationalist in this critical period, Uddin was affected by the political and religious divisions of the era. However, he remained personally opposed to division within Bengali culture. Although he was a Muslim, he grew to love and respect the Hindu culture of his neighbors. In his memoirs, Uddin stressed his strongly held belief that Bengali culture, especially literature, belongs to both Hindus and Muslims. "Th ose who would separate the two [cultures] and write literature will not last many days, I am sure," he wrote.

Uddin was himself affected by this issue. In the 1920s one of his poems was included in the matriculation exam at the University of Calcutta, which caused some controversy among the Hindu majority; his inclusion was defended by his mentor and friend, Professor Dinesh Chandra Sen.

Uddin also treated the theme of religious division in his own writings, especially the long narrative poem "Gipsy Wharf ", which depicts a romance between a Muslim boy and a Hindu girl. In attempting to depict both communities fairly, Uddin created a work that spoke to most Bengali people, and that has survived the test of time.Uddin was also an important folklorist. From 1931 to 1937, as a Ramtanu Lahiri Scholar at the University of Calcutta, he collected several thousand rural Bengali folksongs under the guidance of Professor Sen. In 1938 he left Calcutta to teach at the University of Dhaka. In 1944 he joined the government of East Pakistan in the Department of Information and Broadcasting. He retired as the deputy director of that agency in 1962. During the course of Uddin's career, he collected over ten thousand folksongs, making him one of the most successful folklore collectors of his time. In addition, he wrote important articles and books on the interpretation of Bengali folksongs, folktales and other genres. This scholarly activity gives the AFC recording even greater interest for international scholars in ethnographic disciplines such as folklore, ethnology, and ethnomusicology.

The Jasim Uddin Recording: An Archival History

Staff at the American Folklife Center did not become aware of the importance of the Jasim Uddin recording until September, 2008, when Dr. Jamal Anwar, Uddin's son, contacted AFC to request a copy for the Folk Culture Museum at Jasim Uddin House in Faridpur, Bangladesh. AFC staff made the copy, thus repatriating this small sample of Bengali cultural heritage.

The original recording was made on July 24, 1957, by Sidney Robertson Cowell and her husband, composer Henry Cowell, who were conducting fi eld research in Asia. The recording came to the AFC Archive as part of the Sidney Robertson Cowell Duplication Project, and its history is recounted in a memo written on May 14, 1958, by Rae Korson, then the Head of the Library's Archive of Folk Song, to Harold Spivacke, then Chief of the Library's Music Division:

"Mrs. Cowell recorded twelve double-track tapes of various sizes and has now very generously off ered to permit the Library of Congress to duplicate them for the collections in the Archive of Folk Song.

The Cowells have expressly avoided depositing the recordings elsewhere in the hope that, by being in the Library of Congress, these important sound documents would be available to the greatest number of scholars. The countries represented in this widely varied collection are Iran, India, Pakistan, Burma, Thailand, and Malaysia."During the 1950s, southern and southeastern Asia were represented in the Archive only by thirty-nine short commercial discs from India, a single reel of Pakistani music for the sitar, and two reels of songs and instrumental music made in the Library's recording studio by a visiting Th ai musician. For that reason, Korson explained, "we feel that for this area in particular, we must take advantage of every opportunity which presents itself."

Fortunately, Spivacke agreed, and the duplication project went forward; as a result, the recording has not only been preserved at the Library, but repatriated to Bangladesh, where it can be heard in the museum at Faridpur.Since the 1950s, AFC has greatly expanded its holdings of South Asian materials. The full list of AFC's South Asia collections can be consulted in our online fi nding aid, South Asia Collections in the Archive of Folk Culture, at http://www.loc.gov/folklife/guides/ SouthAsian.html

Endnotes

1 Uddin, Jasim (Jasimuddin). 1939. The Field of the Embroidered Quilt: A Tale of Two Indian Villages (translated from Bengali to English by E.M. Milford). Calcutta: Oxford University Press, Indian Branch.

Source: INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.37 APRIL 2011

HomeLast Modified June 5, 2011