Arsenic victims

Background:

"She was dead. She died three month ago. She was only nine years old ....."

Dr. Akhtar Armad said whisperingly on coming out of a house in Lokpur village of the Bagerhat district, Bangladesh. It was in December 1996. Dr. Armad is a cheerful person and keeps smiling all the time. However, I could see wrinkles between the eyebrows now and even tears in his eyes.He narrated ruefully that he had seen the girl in August, one month prior to her death and told her to take safe water only. He had expected, therefore, to see her in a better shape just like many other patients.

The girl's name is Soma Dutta. There was a photograph of her on the notice board of the National Institute of Preventive & Social Medicine (NIPSOM) in Dhaka, in which Dr. Ahmad is Assistant Professor. In the photograph, Soma is sitting on a bench in the garden, with her palms upward on her thighs, probably to show keratosis on her hands. Her abdomen and legs are so swollen that hepatomegaly and leg edema are suspected (Sachie Tsushima, 2000).

Bangladesh has endured flood, famine and disease. Now it faces the largest mass poisoning in world history - from arsenic. The story begins many years ago, sometimes in the 1960s and 1970s, when national governments and international agencies drew up detailed plans to provide safe water to all. They understood, rightly, that bacteria in water kills more babies than any other substance in the world.

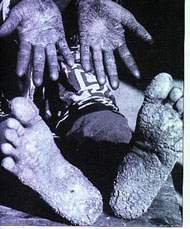

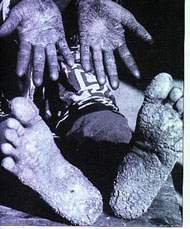

They believed the water on the surface — in millions of ponds and tanks and other water harvesting structures — was contaminated and so invested quickly in new technologies to dig deeper and deeper into the ground. Drills, borepipes, tubewells and handpumps quickly became the triumphalistic instruments of public health missions. Up to 80 million people may be affected, warns the World Health Organisation. Arsenic affects the skin, causing melanosis, keratosis, spotting and scaling, warts and ulcerations, and can eventually lead to gangrene and skin cancer. It attacks most of the body's organs and there is increasing evidence it causes a host of internal cancers and other chronic injuries.

"The people of Bangladesh are being slowly poisoned. Although the world has known this since 1998, the full implications are only just being realised. Up to 57 million of Bangladesh's 130 million inhabitants are drinking water that contains harmful concentrations of arsenic (Editorial, British Medical Journal, 17 March 2001 (2001;322:626-627).

But those figures could be far worse if food is also taking up the toxic element. "Up to now it's been largely ignored," says Andrew Meharg, a biogeochemist at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. With colleague Mazibur Rahman, Meharg sampled soils at 70 sites throughout Bangladesh and rice from seven different regions.

Where there were arsenic-tainted irrigation pumps, the pair found high levels of arsenic in soils. Most of all victims — living in scattered villages across this region. These are “official” victims, whose tubewells are marked in shades of red, to identify its levels of contamination. But then there are the “unofficial” and unidentified victims. Maybe thousands. Maybe millions. Nobody knows because nobody has cared to find out. Even these “victims” do not know. They only know that they are ill. But is the cause of their mysterious illness their water? Where do they go to find out?

While government was well-intentioned in its quest for clean water, it was equally callous, indeed criminal, when it came to responding to the news that was filtering in that maybe, just maybe, the 'strange' diseases are linked to the water that people are drinking. It responded with denial. It responded with misinformation, confusion and ineptitude. Science and its uncertainty became the servile tool for inaction. This subplot is marked by sheer and gross incompetence in efforts to identify the problem, its cause and to find alternatives. This subplot leads to deadly and terrible disease.

The story is therefore, most of all about victims - living in scattered villages across this region. These are "official" victims, whose tubewells are marked in shades of red, to identify its levels of contamination. But then there are the "unofficial" and unidentified victims. Maybe thousands. Maybe millions. Nobody knows because nobody has cared to find out. Even these "victims" do not know. They only know that they are ill. But is the cause of their mysterious illness their water? Where do they go to find out?

It is a story about underground water: when the nectar turns into poison. When a daily task of drinking water from the handpump becomes the source of crippling disease and death. This is not a “natural” disaster — where natural arsenic , present deep down, just happened to make their way into drinking water. It is about a deliberate poisoning. Created by successive governments and multilateral agencies: all well intentioned in their quest for safer, cleaner water supply; all investing in boring into the ground, till they brought the dark zone into the light of daily life (Down to the Earth, 13. 07. 03).

The arsenic, a slow, sadistic killer, has just about finished its work on Fazila Khatun. She teeters now. The fatigue is constant. Pain pulses through her limbs. Warts and sores cover the palms of her hands and the soles of her feet, telltale of the long years of creeping poison.

Mrs. Khatun is hardly alone in this suffering. Bangladesh is in the midst of what the World Health Organization calls the "largest mass poisoning of a population in history." Tens of thousands of Bangladeshis show the outward signs of the same decline. Some 35 million are drinking arsenic-contaminated water, the poison accumulating within them day by day, sip by sip. Here in the village of Chotobinar Chap, with the cancer pulling her under, Mrs. Khatun seems to have surrendered. She has no strength for work. She has no appetite for meals. She lies in a spare room beneath a thatched roof.

"I feel myself fading away, and sometimes I ask God to take me," she muttered. "My husband has abandoned me. He doesn't even look at me anymore" (The New York Times (14. 07. 03).

Statistics

of Arsenic Calamity

Total

Number of districts in Bangladesh

64

Total

Area of Bangladesh

148,393

sq.km

Total

Population of Bangladesh

120

Million

GDP

per capita (1998)

US$260

WHO

arsenic drinking water standard

0,01ppm

Maximum

permissible limit of arsenic in drinking water of Bangladesh

0,005pm

Number

of districts surveyed for arsenic contamination

64

Number

of districts having arsenic above maximum permissible limit

59

Area

of affected 59 districts

126,134

sq.km

Population

at risk of the affected districts

75

Million

Potentially

exposed population

24

Million

Number

of patients suffering from arsenicosis

7000

Total

number of tubewells in Bangladesh

4

Million

Source:

BBS, Dhaka Community Hospital, NIPSOM, DPHE.

. "Chronic arsenic exposure through drinking water has the potential to cause adverse pregnancy outcomes, the weekly meeting of Green Force under the auspices of Bangladesh Paribesh Andolan (BAPA) was told yesterday. Green Force, a BAPA-backed forum of young environment researchers, held the meeting at T.S.C. seminar room. Eight young researchers from home and abroad presented the keynote papers on "Chronic Arsenic Exposure and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Bangladesh." The researchers were Abul Hasnat Milton, Bayzidur Rahman, Ziaul Hasan, Umme Kulsum, Azhar Ali Pramanik, M Rakibuddin, Keith Dear and Wayne Smith (NFB,13 April 03.)."

Arsenic is getting into rice, Bangladesh's staple crop, through irrigation water pumped from contaminated soils, researchers have found. Another study shows that the act of pumping water for irrigation can raise its arsenic levels. The findings worsen the outlook for Bangladesh's water safety crisis.... Where there were arsenic-tainted irrigation pumps, [Meharg & Rahman] found high levels of arsenic in soils. Rice from contaminated regions, contained dangerous levels of arsenic. Rice from elsewhere did not. Three samples contained more than 1.7 milligrams of arsenic per kilogram of rice. The maximum safe level for food in Australia ... is one milligram per kilogram. Rice comprises 73% of a Bangladeshi's caloric intake and arsenic is in much of the country's groundwater.

Doctors warn that in ten years the illness could reach epidemic proportions. Jan Willem Rosenboom, an arsenic expert for the United Nations Children's Fund, believes about 27 per cent of the tubewells people rely on for drinking water are infected at levels above the national standard.

"Poor people in two southern districts [Barisal and Faridpur] having no access to safe potable water, drinking poison with water and inching towards dire consequences of arsenic. These people, who are already fighting poverty, also have no access to treatment to beat the arsenic poisoning. The people with arsenicosis in Barisal and Faridpur are heading towards immature end of their life since they have no ability to get the medicines from markets, local sources said. Experts say there is no permanent answer to arsenic contamination yet, but some physicians prescribe increased protein intake, skin ointments (Salicylic Acid) and anti-oxidant tablet (Rex) as interim treatments to arsenicosis, a ground water chemical contamination that has posed a serious threat to safe drinking water for millions (New Nation, 10. 05. 03).

This dimension of the arsenic contamination problem simply beggars belief. As uk-based science journalist Fred Pearce puts it in his article Bangladesh’s arsenic poisoning: who’s to blame?: “Who knew what and when?”

A Bangladeshi MP, Rabeya Bhuyian, has accused The World Bank, the United Nations Children's Fund, the World Health Organisation and the United Nations Development Programme of failing to protect the water supply (BBC, Oct 6, 1999)

Three years before the BGS study of water quality in Bangladesh, the environmental organisation published findings on 'routine' tests for arsenic in ground-water in the UK.

From the Moray Basin in Scotland to West Devon, underground water sources throughout Britain were tested for arsenic. The BGS team did not find UK arsenic levels significantly in excess of European limits, but they noted in their 1989 report that arsenic in groundwater was considered 'toxic or undesirable in excessive amounts'.

Professor John McArthur, a leading geoscientist from University College London, said that following the UK tests the BGS should have tested for arsenic in Bangladesh. 'They did a country-wide test in the UK, they included arsenic in that country-wide test - so why they didn't do it in Bangladesh is a mystery.'

Martyn Day of Leigh Day believes the legal action could set a precedent for both the Third World and geological scientists. 'I think it's absolutely right that when a group like the BGS come out to a developing country like Bangladesh they are forced to apply exactly the same standards they would apply if they were testing water in Salisbury, or London, or any where else in Britain. The whole of the aid world, the whole of the geological world, will be watching this case.'

He added: 'If the BGS had tested for arsenic in 1992, somebody would have pressed the panic button, and this would have brought in all the mitigation projects. All the evidence we have suggests that many people would not have gone down with arsenic-related illnesses.'

Professor Mahmuder Rahman from the Dhaka Community Hospital is among those who now believe that, in addition to the BGS, Unicef must take responsibility for the potential disaster. He said there was growing anger in the country at the part played by Western experts and aid agencies in the crisis.

Critics of the BGS survey say the guidelines over testing water supplies were clearly standardised by the World Health Organisation. From 1968 onwards a number of scientific papers reported on concerns about arsenic in groundwater in Taiwan, Hungary, the US, and West Bengal in India. In 1984 the World Health Organisation set down guidelines for arsenic content in drinking water

In London, legal proceedings have begun in the High Court to decide whether a British organisation was negligent in failing to detect it. The British Geological Survey, which conducted research on behalf of the Bangladesh government in 1992, is accused of not testing for it and giving the groundwater a clean bill of health. It argues that, at the time of its report, little was known about the geological origins of arsenic poisoning. The decision could have implications for hundreds of Bangladeshis who claim to be suffering from arsenic poisoning. It is also likely to have a broader impact on the potential liability of other scientists employed on aid projects in developing countries. "This is of great concern to the scientific community and those who fund it," one lawyer told the court yesterday (10. 05. 03)."

"Arsenic poisoning in Bangladesh has been a tragedy for many thousands of villagers that may well have been prevented, or certainly ameliorated, if the defendants had done their job properly," said Martin Day, one the solicitors working for the Bangladeshis.

(The Gurdian U.K., May 9, 2003)

British scientists 'failed to check for arsenic risk'

British scientists failed to detect dangerous levels of arsenic in the supply of drinking water implicated in the biggest mass poisoning in history.

Two studies of groundwater quality in Bangladesh carried out by British hydrologists failed to monitor natural arsenic levels even though the testing was suggested in voluntary guidelines drawn up by the World Health Organisation

The British Geological Survey (BGS), the UK's most prestigious hydrology centre, carried out the studies on behalf of the Bangladeshi government in the mid-1980s and early-1990s, more than six years before arsenic was shown to be the cause of the mystery illnesses affecting millions of people.

John McArthur, the professor of geochemistry at University College London, said that if the BGS scientists had followed the WHO guidelines, much of the suffering and many of the deaths might have been avoided..

"If they had tested for arsenic they would have been able to press the panic button. They would have been believed and the world would have known about it long before it did," Professor McArthur said.

"If they had looked for arsenic they could have found it – there is no question of that – and remedial action could have happened five or eight years before it did."

Millions of Bangladeshis are suffering from arsenic poisoning as a result of drinking contaminated water drawn from some of the 10 million new wells sunk over the past 25 years as part of an international development programme aimed at providing clean drinking water.

Many of the residents of Bangladesh's 68,000 villages suffer from the early stages of poisoning, such as ulcerous skin growths. The final stages are gangrene and cancer and an estimated 20,000 people a year have died in the tragedy

Professor McArthur is critical of the oversight that resulted in the BGS failing to find arsenic. "They did not find arsenic because they did not look for it, even though there were routine, well-established techniques for doing so," he said. "They should have analysed for all the trace elements in the WHO guidelines – and that included arsenic."

"Nevertheless, it was and remains common practice not to measure all the determinands [sic] on the list ... for reasons of cost and/or availability of facilities," Dr Peach wrote in a statement. "Some judgement always needs to be made commensurate with the scale of the resources available and the perceived – at the time – likelihood of a problem. In retrospect, we – and others – made a mistake."

The BGS said that there was no reason why it should have tested for arsenic given that the scale of the problem did not emerge until the middle of 1997 onwards. Arsenic was not routinely measured by most water-quality labs because it was not widely thought to be a problem in groundwater, other than in mining regions, it said.

However, Professor McArthur said there was no excuse for the BGS not to know about the WHO's guidelines on arsenic. "If one really wanted to be charitable to the BGS, you'd excuse them for not finding it the first time, but failing to look a second time appears to be inexcusable."

Source: Steve Connor and Fred Pearce, Independent, 19 January 2001

Arsenic victims win right to trial

Lawyers representing some 750 victims of arsenic poisoning in Bangladesh have won the first stage of a legal battle in London in which they are accusing a British survey organisation of negligence.

The High Court ruled that the British Geological Survey had a case to answer over claims it should have carried out tests for arsenic in a 1992 survey on the toxicity of Bangladesh well water.

The judge, Mr Justice Simon, ruled that the case should go to full trial. In its attempt to have the case dismissed, the BSG said its survey was part of an irrigation project, and had nothing to do with drinking water. Some reports suggest arsenic in groundwater in Bangladesh and eastern India has affected millions of people, and caused up to 3,000 deaths a year. (Source: BBC World Service, Thursday, 8 May, 2003, 17:34 GMT)

Scientists facing action over Bangladesh water survey

A damages action that alleges British government-backed scientists were negligent when they assessed groundwater supplies in Bangladesh, is to go ahead after a ruling in the High Court in London late last week. The decision could have implications for hundreds of Bangladeshis who claim to be suffering from arsenic poisoning. It is also likely to have a broader impact on the potential liability of other scientists employed on aid projects in developing countries. "This is of great concern to the scientific community and those who fund it," one lawyer told the court yesterday." (Source: Nikki Tait, FT Syndication Service - 10 May, 2003. NFB)

People of 2 dists drink poison with water

Poor people in two southern districts having no access to safe potable water, drinking poison with water and inching towards dire consequences of arsenic.

These people, who are already fighting poverty, also have no access to treatment to beat the arsenic poisoning.

The people with arsenicosis in Barisal and Faridpur are heading towards immature end of their life since they have no ability to get the medicines from markets, local sources said.

Rizia Begum (40) of village Balihatibazar under Bhanga upazila, tested arsenicosis positive just five months ago with itching in skins and pain in muscles. She told a group of visiting journalists recently that she was gradually getting weaker. An uncertain future is haunting her since she is not getting any treatment.

“But the pain is still existing. I want to buy some medicine. To that end I am saving Taka one or two from earning of my tennage son,” Rizia said

Many hit by arsenic in Khudrakati Village under Babuganj upazila in Barisal district echoed the concern of Rizia saying they are also drinking the poison for the past three year since they have no access to safe water

The government has made some arrangement of safe water but that too short to meet the requirement, she added. Women arsenicosis patients in the village said they could get medicines from a nearby upazila hospital earlier spending Taka 50, but that too has gone because there is no supply in the hospital now. Some of them said to afford Taka 50 a week is very difficult for them.

“We buy ointment to reduce skin itching and the tablets to check muscle pull. But this medicine is now in short supply, which has increased our suffering manifold,” Aklima Akter, a student of class ten and also a patient said.

(Source: BSS, Dhaka May 10, 2003, )

Last modified: August 24, 2004.

|  |

|

Background:

"She was dead. She died three month ago. She was only nine years old ....." Dr. Akhtar Armad said whisperingly on coming out of a house in Lokpur village of the Bagerhat district, Bangladesh. It was in December 1996. Dr. Armad is a cheerful person and keeps smiling all the time. However, I could see wrinkles between the eyebrows now and even tears in his eyes.He narrated ruefully that he had seen the girl in August, one month prior to her death and told her to take safe water only. He had expected, therefore, to see her in a better shape just like many other patients.

The girl's name is Soma Dutta. There was a photograph of her on the notice board of the National Institute of Preventive & Social Medicine (NIPSOM) in Dhaka, in which Dr. Ahmad is Assistant Professor. In the photograph, Soma is sitting on a bench in the garden, with her palms upward on her thighs, probably to show keratosis on her hands. Her abdomen and legs are so swollen that hepatomegaly and leg edema are suspected (Sachie Tsushima, 2000).

Bangladesh has endured flood, famine and disease. Now it faces the largest mass poisoning in world history - from arsenic. The story begins many years ago, sometimes in the 1960s and 1970s, when national governments and international agencies drew up detailed plans to provide safe water to all. They understood, rightly, that bacteria in water kills more babies than any other substance in the world.

They believed the water on the surface — in millions of ponds and tanks and other water harvesting structures — was contaminated and so invested quickly in new technologies to dig deeper and deeper into the ground. Drills, borepipes, tubewells and handpumps quickly became the triumphalistic instruments of public health missions. Up to 80 million people may be affected, warns the World Health Organisation. Arsenic affects the skin, causing melanosis, keratosis, spotting and scaling, warts and ulcerations, and can eventually lead to gangrene and skin cancer. It attacks most of the body's organs and there is increasing evidence it causes a host of internal cancers and other chronic injuries."The people of Bangladesh are being slowly poisoned. Although the world has known this since 1998, the full implications are only just being realised. Up to 57 million of Bangladesh's 130 million inhabitants are drinking water that contains harmful concentrations of arsenic (Editorial, British Medical Journal, 17 March 2001 (2001;322:626-627).

But those figures could be far worse if food is also taking up the toxic element. "Up to now it's been largely ignored," says Andrew Meharg, a biogeochemist at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. With colleague Mazibur Rahman, Meharg sampled soils at 70 sites throughout Bangladesh and rice from seven different regions. Where there were arsenic-tainted irrigation pumps, the pair found high levels of arsenic in soils. Most of all victims — living in scattered villages across this region. These are “official” victims, whose tubewells are marked in shades of red, to identify its levels of contamination. But then there are the “unofficial” and unidentified victims. Maybe thousands. Maybe millions. Nobody knows because nobody has cared to find out. Even these “victims” do not know. They only know that they are ill. But is the cause of their mysterious illness their water? Where do they go to find out?

While government was well-intentioned in its quest for clean water, it was equally callous, indeed criminal, when it came to responding to the news that was filtering in that maybe, just maybe, the 'strange' diseases are linked to the water that people are drinking. It responded with denial. It responded with misinformation, confusion and ineptitude. Science and its uncertainty became the servile tool for inaction. This subplot is marked by sheer and gross incompetence in efforts to identify the problem, its cause and to find alternatives. This subplot leads to deadly and terrible disease.

The story is therefore, most of all about victims - living in scattered villages across this region. These are "official" victims, whose tubewells are marked in shades of red, to identify its levels of contamination. But then there are the "unofficial" and unidentified victims. Maybe thousands. Maybe millions. Nobody knows because nobody has cared to find out. Even these "victims" do not know. They only know that they are ill. But is the cause of their mysterious illness their water? Where do they go to find out?

It is a story about underground water: when the nectar turns into poison. When a daily task of drinking water from the handpump becomes the source of crippling disease and death. This is not a “natural” disaster — where natural arsenic , present deep down, just happened to make their way into drinking water. It is about a deliberate poisoning. Created by successive governments and multilateral agencies: all well intentioned in their quest for safer, cleaner water supply; all investing in boring into the ground, till they brought the dark zone into the light of daily life (Down to the Earth, 13. 07. 03).

The arsenic, a slow, sadistic killer, has just about finished its work on Fazila Khatun. She teeters now. The fatigue is constant. Pain pulses through her limbs. Warts and sores cover the palms of her hands and the soles of her feet, telltale of the long years of creeping poison. Mrs. Khatun is hardly alone in this suffering. Bangladesh is in the midst of what the World Health Organization calls the "largest mass poisoning of a population in history." Tens of thousands of Bangladeshis show the outward signs of the same decline. Some 35 million are drinking arsenic-contaminated water, the poison accumulating within them day by day, sip by sip. Here in the village of Chotobinar Chap, with the cancer pulling her under, Mrs. Khatun seems to have surrendered. She has no strength for work. She has no appetite for meals. She lies in a spare room beneath a thatched roof. "I feel myself fading away, and sometimes I ask God to take me," she muttered. "My husband has abandoned me. He doesn't even look at me anymore" (The New York Times (14. 07. 03).

Statistics of Arsenic Calamity

Total Number of districts in Bangladesh 64 Total Area of Bangladesh 148,393 sq.km Total Population of Bangladesh 120 Million GDP per capita (1998) US$260 WHO arsenic drinking water standard 0,01ppm Maximum permissible limit of arsenic in drinking water of Bangladesh 0,005pm Number of districts surveyed for arsenic contamination 64 Number of districts having arsenic above maximum permissible limit 59 Area of affected 59 districts 126,134 sq.km Population at risk of the affected districts 75 Million Potentially exposed population 24 Million Number of patients suffering from arsenicosis 7000 Total number of tubewells in Bangladesh 4 Million Source: BBS, Dhaka Community Hospital, NIPSOM, DPHE.

. "Chronic arsenic exposure through drinking water has the potential to cause adverse pregnancy outcomes, the weekly meeting of Green Force under the auspices of Bangladesh Paribesh Andolan (BAPA) was told yesterday. Green Force, a BAPA-backed forum of young environment researchers, held the meeting at T.S.C. seminar room. Eight young researchers from home and abroad presented the keynote papers on "Chronic Arsenic Exposure and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Bangladesh." The researchers were Abul Hasnat Milton, Bayzidur Rahman, Ziaul Hasan, Umme Kulsum, Azhar Ali Pramanik, M Rakibuddin, Keith Dear and Wayne Smith (NFB,13 April 03.)."

Arsenic is getting into rice, Bangladesh's staple crop, through irrigation water pumped from contaminated soils, researchers have found. Another study shows that the act of pumping water for irrigation can raise its arsenic levels. The findings worsen the outlook for Bangladesh's water safety crisis.... Where there were arsenic-tainted irrigation pumps, [Meharg & Rahman] found high levels of arsenic in soils. Rice from contaminated regions, contained dangerous levels of arsenic. Rice from elsewhere did not. Three samples contained more than 1.7 milligrams of arsenic per kilogram of rice. The maximum safe level for food in Australia ... is one milligram per kilogram. Rice comprises 73% of a Bangladeshi's caloric intake and arsenic is in much of the country's groundwater.

Doctors warn that in ten years the illness could reach epidemic proportions. Jan Willem Rosenboom, an arsenic expert for the United Nations Children's Fund, believes about 27 per cent of the tubewells people rely on for drinking water are infected at levels above the national standard.

"Poor people in two southern districts [Barisal and Faridpur] having no access to safe potable water, drinking poison with water and inching towards dire consequences of arsenic. These people, who are already fighting poverty, also have no access to treatment to beat the arsenic poisoning. The people with arsenicosis in Barisal and Faridpur are heading towards immature end of their life since they have no ability to get the medicines from markets, local sources said. Experts say there is no permanent answer to arsenic contamination yet, but some physicians prescribe increased protein intake, skin ointments (Salicylic Acid) and anti-oxidant tablet (Rex) as interim treatments to arsenicosis, a ground water chemical contamination that has posed a serious threat to safe drinking water for millions (New Nation, 10. 05. 03).

This dimension of the arsenic contamination problem simply beggars belief. As uk-based science journalist Fred Pearce puts it in his article Bangladesh’s arsenic poisoning: who’s to blame?: “Who knew what and when?”

A Bangladeshi MP, Rabeya Bhuyian, has accused The World Bank, the United Nations Children's Fund, the World Health Organisation and the United Nations Development Programme of failing to protect the water supply (BBC, Oct 6, 1999)

Three years before the BGS study of water quality in Bangladesh, the environmental organisation published findings on 'routine' tests for arsenic in ground-water in the UK. From the Moray Basin in Scotland to West Devon, underground water sources throughout Britain were tested for arsenic. The BGS team did not find UK arsenic levels significantly in excess of European limits, but they noted in their 1989 report that arsenic in groundwater was considered 'toxic or undesirable in excessive amounts'.

Professor John McArthur, a leading geoscientist from University College London, said that following the UK tests the BGS should have tested for arsenic in Bangladesh. 'They did a country-wide test in the UK, they included arsenic in that country-wide test - so why they didn't do it in Bangladesh is a mystery.'

Martyn Day of Leigh Day believes the legal action could set a precedent for both the Third World and geological scientists. 'I think it's absolutely right that when a group like the BGS come out to a developing country like Bangladesh they are forced to apply exactly the same standards they would apply if they were testing water in Salisbury, or London, or any where else in Britain. The whole of the aid world, the whole of the geological world, will be watching this case.' He added: 'If the BGS had tested for arsenic in 1992, somebody would have pressed the panic button, and this would have brought in all the mitigation projects. All the evidence we have suggests that many people would not have gone down with arsenic-related illnesses.'

Professor Mahmuder Rahman from the Dhaka Community Hospital is among those who now believe that, in addition to the BGS, Unicef must take responsibility for the potential disaster. He said there was growing anger in the country at the part played by Western experts and aid agencies in the crisis.

Critics of the BGS survey say the guidelines over testing water supplies were clearly standardised by the World Health Organisation. From 1968 onwards a number of scientific papers reported on concerns about arsenic in groundwater in Taiwan, Hungary, the US, and West Bengal in India. In 1984 the World Health Organisation set down guidelines for arsenic content in drinking water

In London, legal proceedings have begun in the High Court to decide whether a British organisation was negligent in failing to detect it. The British Geological Survey, which conducted research on behalf of the Bangladesh government in 1992, is accused of not testing for it and giving the groundwater a clean bill of health. It argues that, at the time of its report, little was known about the geological origins of arsenic poisoning. The decision could have implications for hundreds of Bangladeshis who claim to be suffering from arsenic poisoning. It is also likely to have a broader impact on the potential liability of other scientists employed on aid projects in developing countries. "This is of great concern to the scientific community and those who fund it," one lawyer told the court yesterday (10. 05. 03)."

"Arsenic poisoning in Bangladesh has been a tragedy for many thousands of villagers that may well have been prevented, or certainly ameliorated, if the defendants had done their job properly," said Martin Day, one the solicitors working for the Bangladeshis. (The Gurdian U.K., May 9, 2003)

British scientists 'failed to check for arsenic risk'

British scientists failed to detect dangerous levels of arsenic in the supply of drinking water implicated in the biggest mass poisoning in history. Two studies of groundwater quality in Bangladesh carried out by British hydrologists failed to monitor natural arsenic levels even though the testing was suggested in voluntary guidelines drawn up by the World Health Organisation

The British Geological Survey (BGS), the UK's most prestigious hydrology centre, carried out the studies on behalf of the Bangladeshi government in the mid-1980s and early-1990s, more than six years before arsenic was shown to be the cause of the mystery illnesses affecting millions of people. John McArthur, the professor of geochemistry at University College London, said that if the BGS scientists had followed the WHO guidelines, much of the suffering and many of the deaths might have been avoided..

"If they had tested for arsenic they would have been able to press the panic button. They would have been believed and the world would have known about it long before it did," Professor McArthur said. "If they had looked for arsenic they could have found it – there is no question of that – and remedial action could have happened five or eight years before it did."

Millions of Bangladeshis are suffering from arsenic poisoning as a result of drinking contaminated water drawn from some of the 10 million new wells sunk over the past 25 years as part of an international development programme aimed at providing clean drinking water. Many of the residents of Bangladesh's 68,000 villages suffer from the early stages of poisoning, such as ulcerous skin growths. The final stages are gangrene and cancer and an estimated 20,000 people a year have died in the tragedy

Professor McArthur is critical of the oversight that resulted in the BGS failing to find arsenic. "They did not find arsenic because they did not look for it, even though there were routine, well-established techniques for doing so," he said. "They should have analysed for all the trace elements in the WHO guidelines – and that included arsenic."

"Nevertheless, it was and remains common practice not to measure all the determinands [sic] on the list ... for reasons of cost and/or availability of facilities," Dr Peach wrote in a statement. "Some judgement always needs to be made commensurate with the scale of the resources available and the perceived – at the time – likelihood of a problem. In retrospect, we – and others – made a mistake." The BGS said that there was no reason why it should have tested for arsenic given that the scale of the problem did not emerge until the middle of 1997 onwards. Arsenic was not routinely measured by most water-quality labs because it was not widely thought to be a problem in groundwater, other than in mining regions, it said.

However, Professor McArthur said there was no excuse for the BGS not to know about the WHO's guidelines on arsenic. "If one really wanted to be charitable to the BGS, you'd excuse them for not finding it the first time, but failing to look a second time appears to be inexcusable."

Source: Steve Connor and Fred Pearce, Independent, 19 January 2001

Arsenic victims win right to trial

Lawyers representing some 750 victims of arsenic poisoning in Bangladesh have won the first stage of a legal battle in London in which they are accusing a British survey organisation of negligence.

The High Court ruled that the British Geological Survey had a case to answer over claims it should have carried out tests for arsenic in a 1992 survey on the toxicity of Bangladesh well water.

The judge, Mr Justice Simon, ruled that the case should go to full trial. In its attempt to have the case dismissed, the BSG said its survey was part of an irrigation project, and had nothing to do with drinking water. Some reports suggest arsenic in groundwater in Bangladesh and eastern India has affected millions of people, and caused up to 3,000 deaths a year. (Source: BBC World Service, Thursday, 8 May, 2003, 17:34 GMT)

Scientists facing action over Bangladesh water survey

A damages action that alleges British government-backed scientists were negligent when they assessed groundwater supplies in Bangladesh, is to go ahead after a ruling in the High Court in London late last week. The decision could have implications for hundreds of Bangladeshis who claim to be suffering from arsenic poisoning. It is also likely to have a broader impact on the potential liability of other scientists employed on aid projects in developing countries. "This is of great concern to the scientific community and those who fund it," one lawyer told the court yesterday." (Source: Nikki Tait, FT Syndication Service - 10 May, 2003. NFB)

People of 2 dists drink poison with water

Poor people in two southern districts having no access to safe potable water, drinking poison with water and inching towards dire consequences of arsenic. These people, who are already fighting poverty, also have no access to treatment to beat the arsenic poisoning. The people with arsenicosis in Barisal and Faridpur are heading towards immature end of their life since they have no ability to get the medicines from markets, local sources said.

Rizia Begum (40) of village Balihatibazar under Bhanga upazila, tested arsenicosis positive just five months ago with itching in skins and pain in muscles. She told a group of visiting journalists recently that she was gradually getting weaker. An uncertain future is haunting her since she is not getting any treatment. “But the pain is still existing. I want to buy some medicine. To that end I am saving Taka one or two from earning of my tennage son,” Rizia said

Many hit by arsenic in Khudrakati Village under Babuganj upazila in Barisal district echoed the concern of Rizia saying they are also drinking the poison for the past three year since they have no access to safe water

The government has made some arrangement of safe water but that too short to meet the requirement, she added. Women arsenicosis patients in the village said they could get medicines from a nearby upazila hospital earlier spending Taka 50, but that too has gone because there is no supply in the hospital now. Some of them said to afford Taka 50 a week is very difficult for them. “We buy ointment to reduce skin itching and the tablets to check muscle pull. But this medicine is now in short supply, which has increased our suffering manifold,” Aklima Akter, a student of class ten and also a patient said.

(Source: BSS, Dhaka May 10, 2003, )

Last modified: August 24, 2004.