"I don't fear death. I am only afraid of the fate of my daughter and wife if I die"

Motahar Hossain recognised what his mangled hands and feet meant. It was the first step he had witnessed in the slow deaths of his four older brothers. After the hands became useless with thick, painful sores the bloody vomiting began, and then various organs would rot away, until the body could no longer sustain life.

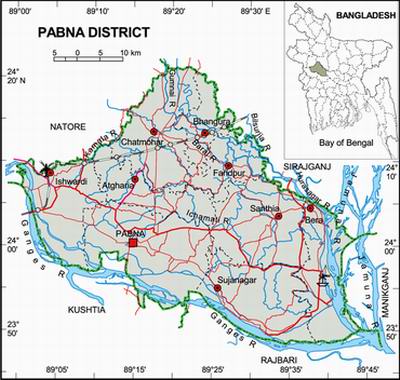

By the time the black and white sores on Hossain's hands and feet had grown too thick and filled with puss to spend the day farming his small plot of land in Pabna, it didn't really matter. He was too weak with heart palpitations to harvest the rice that supported his family.

Motahar Hossain recognised what his mangled hands and feet meant. It was the first step he had witnessed in the slow deaths of his four older brothers. After the hands became useless with thick, painful sores the bloody vomiting began, and then various organs would rot away, until the body could no longer sustain life.

By the time the black and white sores on Hossain's hands and feet had grown too thick and filled with puss to spend the day farming his small plot of land in Pabna, it didn't really matter. He was too weak with heart palpitations to harvest the rice that supported his family.

'I don't fear death. I am only afraid of the fate of my daughter and wife if I die. I have no brothers left to support them if I am gone,' said Hossain.

Hossain is one of the 50 million people of Bangladesh who are feeling the effects of drinking water naturally contaminated with dangerous levels of arsenic over many years. For the past 30 years drinking water has been obtained during the months of the dry season by digging deep and shallow tubewells, equipped with hand pumps. Non-government organisations (NGOs) and the government have pitted the land with over 10 million tubewells since liberation in 1971, and by 1998, 97 per cent of the population was pumping their daily water from underground sources.

It wasn't until many had died that it was found in 1996 by the Dhaka Community Hospital that underground water was the culprit. The sores had been passed off as the result of skin diseases. They were told to put on some ointment and wait for it to heal. The lung cancer and kidney failure were passed off as misfortune. Arsenic was mentioned for the first time in a small health clinic in the outskirts of Pabna.

'Arsenic, a toxic element, is teaching a bitter lesson to mankind, particularly to those who have been suffering from arsenicosis. The excessive level of arsenic in drinking water is re-defining water from 'lifesaver' to a 'threat' to human survival,' said Khondoker Mokadem Hossain, Ph.D, Professor, Department of Sociology, Dhaka University, at the 4th International Arsenic Conference.

The amount of time it takes for the deadly water to take its toll on the body varies, said Mustafizar Rahman, Training Coordinator of the Pabna Community Clinic, a branch of the Dhaka Community Hospital. Some are showing signs of arsenic poisoning as early as 5 or 6 years old, he added.

Down dirt roads and along city streets tubewells provide water for single families and entire villages. The first gamble is the level of arsenic in the water. In the Madaripur District, water samples were found by the School of Environmental Studies, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India to be 200 times that of safe limits, and individuals were found to contain 25 times the amount of arsenic metabolites in their systems in comparison to control groups drinking arsenic-free water.

There are 10 million tubewells in Bangladesh. To date 100,000 have been tested for arsenic, and nearly 70 per cent of them have been marked with a large red X or have had their spouts painted red to show that they are unsafe. In some cases, as in the village of Radhanagor where Hossain lives, there is only one tubewell left that provides safe drinking water. So they cart water pails back and forth and pray that the water will continue to replenish itself. Once it is gone they will have to walk three kilometres to the nearest safe water source. Or, drink a daily dose of natural poison.

Thirsty, growing, gulping kids could be feeling the effects sooner because of the high amounts of water they take throughout the hot, humid days in Bangladesh. Men and women working under the hot sun also up their intake. The amount of water consumed, combined with the levels of arsenic in the water, begin to build the hand that will be played.

A well-balanced diet with regular protein fights the effects of arsenic. In Bangladesh the basic diet consists mainly of rice and vegetables. Protein is scarce and so is the nutritional support of the body to fight the invading arsenic. Having any food at all with water helps to absorb some of the dangerous chemical. Some people are genetically prone to such problems, said Rahman, and this is where individual immune systems become a factor.

On an average, he added, 7-10 years of drinking contaminated water will have affected you with lifelong symptoms. The number of people who are affected is unknown, although it is known that number has seven digits.

Hasina Khatun of Saidpur Uzan Para washed her vegetables and carried them off to the local market every week until she realised that no one was buying them. There was a rumour that a plague was sweeping through her village, and that was why so many had died recently, she said. So she stopped going. Arsenic poisoning was taking more than their lives; it was taking their livelihood.

Marriage and children are an expected part of life, said Maher of Comilla. When she started growing abscesses on her hands at the age of 15, she began to worry. Now she is 23 and the disease has progressed. She spends her days lying in a bed at the Dhaka Community Hospital, hoping for a cure.

Ailments caused by arsenic are widespread, and many are deadly. According to R.N. Ratnaike, of the University of Adelaide, the early symptoms include nausea, vomiting, profuse watery diarrhoea, abdominal pain, excessive salivation and seizures. Skin changes and heart and nervous system disease follow. After prolonged consumption of arsenic-laced water, malignant changes occur in a variety of organs, linking the toxin to cancers of the skin, lung, liver, kidney and bladder.

Although much damage has been done, the long, slow road to recovery for the country is under way.

After the initial diagnosis in 1996, a team of skin specialists was formed. Samples were taken of well water, and human skin, hair, nails and urine. The School of Environmental Studies in Jadavpar, Kolkata took them for testing. The results were shocking, and researchers said that immediate action was necessary.

An arsenic unit, named the 'Rapid Action Programme' was formed at the Dhaka Community Hospital, with clinics in each infected district in Dhaka.

'The main challenge now is to test all the tubewells and to provide arsenic-free water to the millions of people who are drinking arsenic-contaminated water,' said Dr. Rashid Hasan of the Pabna Community Clinic.

The first phase of the programme focuses on making people aware of the problem, and of avenues that are available for their health and water needs. The Dhaka Community Hospital trains health workers to go from door to door, giving basic health screening tests and spreading the word about the effects of drinking arsenic-contaminated water. The process is slow, and outside help has been minimal, said Professor Quazi Quamruzzaman, Chairman of the Dhaka Community Hospital.

The NGOs and the government sank tubewells and turned their backs. For nearly six years the Dhaka Community Hospital has been working with the people. We went from door to door, asking for help to fight against arsenic, but no one has shown any interest in helping. The level of corruption is high. It is so painful, you feel so helpless when you know that millions of dollars have been spent in the name of arsenic, and nothing has been done,' said Quamruzzaman.

The beginning stages of a five-year plan are underway at the Dhaka Community Hospital. Districts are divided, tubewells are tested and marked with green X's if they are safe, red X's if they are not. Door-to-door health workers identify arsenic poisoning in patients, and the worst cases are sent to Dhaka for treatment.

But in most cases there is not much that can be done, said Dr. Hasan.

Every Thursday he sits in a two-room shack at the end of a dusty road in Pabna and tells patients that he has no cure for their blistered hands and weakening heart. He tends to the symptoms, and then sends them home to drink the water that caused them. The worst cases are sent to hospitals for chemo-therapy and constant care, although often the hospitals are unprepared for the arsenic-related epidemic, he added.

The social workers of the Dhaka Community Hospital are working to get the villages involved by teaching them what arsenic is, how it affects the body, and how to detect arsenicosis in yourself and others.

After we educate on the dangers of arsenic, we are left with the dilemma of having no solutions to offer that are accessible or affordable. Our locals are poor. Many options are not open to us,' said Professor Satyan Basu, who is working with the Pabna Community Clinic.

On a daily basis tubewells are marked unsafe for drinking in every area of Bangladesh. Options for prolonged safe water are expensive and will take time to implement, said Basu.

Digging shallow ring wells, lining them with plastic and preserving the many inches of rain that falls during the three-month monsoon season can harvest Rainwater. Supplies will last an additional three to four months, leaving the remaining half of the year without an avenue for safe water.

Canals are another option for preserving larger quantities of water. The downfall is the incredible expense they entail, and contamination from high levels of bacteria from still water. Calcium carbonate can be used to clear the bacteria; boiling water is also affective. Millions of dollars would be necessary to put into service enough canals for all of the infected areas of Bangladesh, leaving that solution on hold for now.

Three-layered brick, sand and clay pot tiers have been made by some of the villagers. Water is passed through brick chips that lay in a clay bowl, down through sand, and then through a filter made from simple material. At the end of the process the water has eliminated around 60 per cent of its arsenic and is deemed safe for drinking. Filter companies are searching for the filter system that will take care of the problem and be affordable for all.

'Future considerations need to be both preventative and curative. While many technologies exist for decreasing or eliminating arsenic from drinking water, the costs involved may be prohibitive,' said Ratnaike. He added, 'One of Bangladesh's most valuable assets is its massive sources of as yet untapped, uncontaminated water that may well provide the lasting solution to the great humanitarian problem facing the country.'

(Jessica Russell, Holiday, 30. 05. 2002).